Reggie and Pete are best buds in a South London motorcycle club. Both wear black leather jackets. Reggie (Colin Campbell) has dodgy painted on the back of his; Pete (Dudley Sutton) accessorizes with leather pants. Guess which one is gay? That's the first of many intrigues in the 1964 British film The Leather Boys, a classic example of the type of 1960s filmmaking that helped breed popular acceptance of queerness, despite it being rated "X" by British censors.

It's easy to look back and condescend to the archaic fears in old movies, but The Leather Boys is up front about that fear as experienced by both Reggie and Pete, who worry that their personal identities don't fit into the social conventions of their time and place. Reggie is married right out of school but is unprepared for its attendant sacrifices and commitment; he jumps at the manly freedom that jocular Pete represents. (That dodgy insignia suggests that Reggie is a bit of a tease himself.)

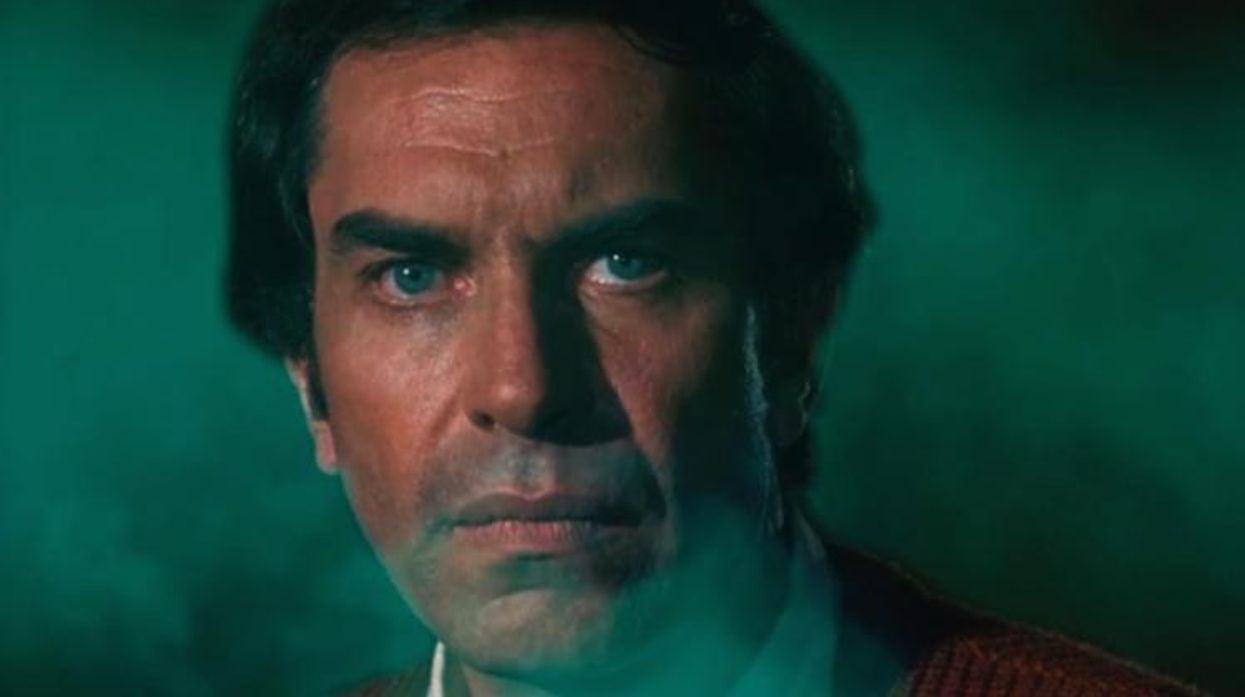

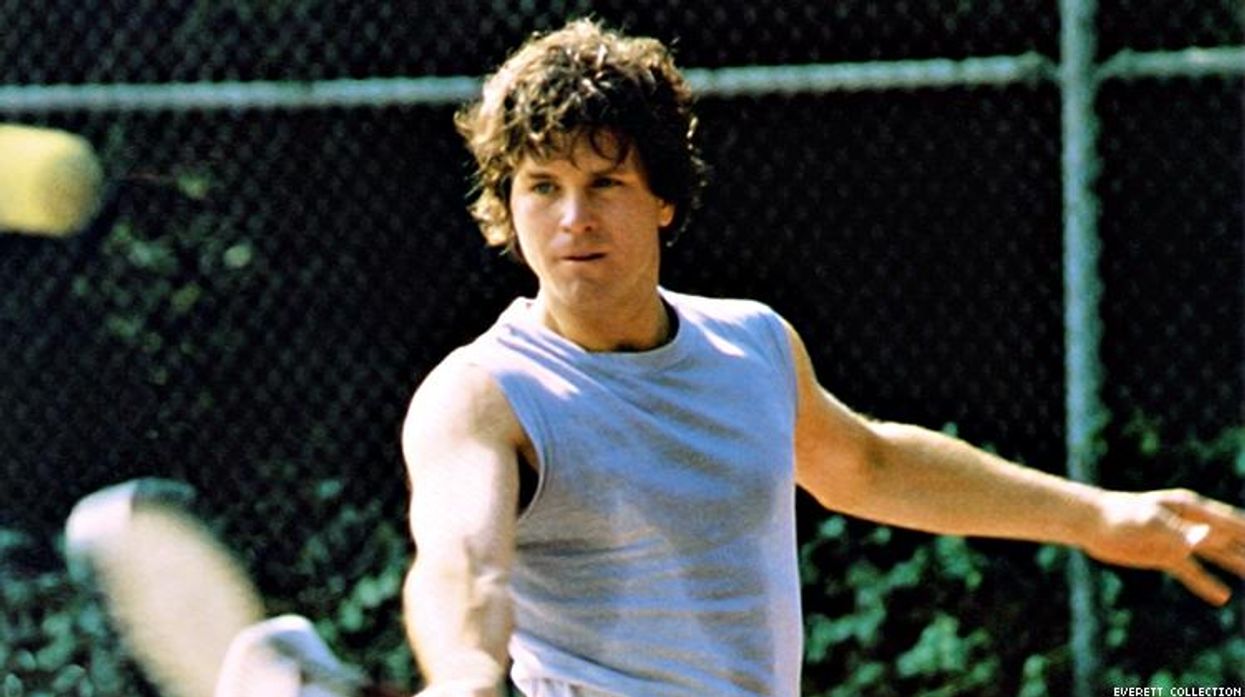

Campbell's dark-haired, brooding Reggie is what used to be called "straight-appearing," while curly-blond Pete's sunny, gregarious manner at first just seems extra-friendly. Director Sidney J. Furie's plain black-and-white realism revs up when the two bikers zoom down a road together. It's the film's first energized scene, drawing upon the biker-movie legacy of Brando's tight-jeaned rebel in The Wild One (1953) and possibly influencing Kenneth Anger's landmark underground movie Scorpio Rising (1965) with its erotic combination of motorcycles, masculinity, and pop music.

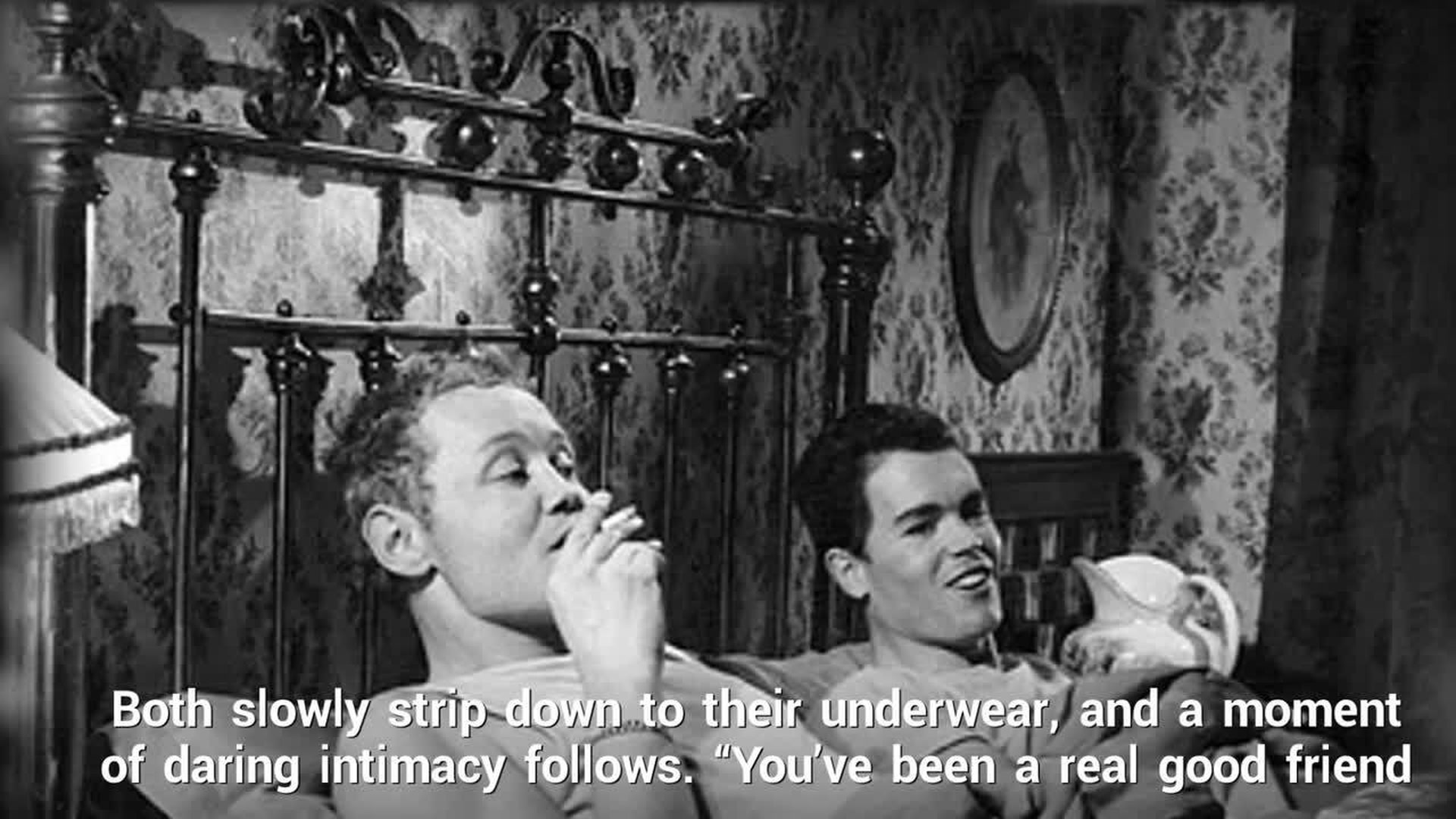

The Leather Boys sets these mischievous elements in a context of traditional working-class heterosexual society. Symbolizing the coming gay revolution, Reggie asks his widowed grandmother to take Pete in as a lodger; that's when the subversive trappings of the biker subculture--all that badass leather--clash with the tasteful tradition and old-lady decor. After a spat between Reggie and his wife, the two friends share a bed in the grandmother's boudoir. Both slowly strip down to their skivvies, and a moment of daring intimacy follows. "You've been a real good friend to me; you're the best friend I ever had," Reggie says before they begin a boyish pillow fight. Given the audience's suspicions about the renegade biker and leather underground, this scene's implications boil over with the suggestiveness of hidden desires ready to be revealed.

But the tricky tentativeness of The Leather Boys is what's fascinating. It followed several "problem pictures" featuring gay characters (Victim, The L-Shaped Room, The Children's Hour), yet director Furie and screenwriter Gillian Freeman--who based the film on Freeman's novel--confronted the social problem in a way that now can be seen as advantageous to the culture's gradual sexual understanding.

Reggie's marital discord with his wife, Dot, bolsters Reggie and Pete's homosocial bromance. Reggie gets something different from Pete than he gets from Dot. He's unsure what it is, but when BFF Pete reminds him, "Don't I look after you well enough?," Reggie replies: "I need a woman, don't I?" Here's where The Leather Boys tries unifying gay-straight friendship.

Note a brief reconciliation between Reggie and Dot: They slow-dance to a jukebox version of what sounds like "What Kind of Fool Am I?," a 1962 hit for showbiz icon and gay-favorite Anthony Newley. The song asks: "What kind of fool am I? / Who never fell in love / It seems that I'm the only one that I have been thinking of / What kind of man is this? / An empty shell / A lonely cell in which an empty heart must dwell?"

The song's questions reveal Reggie's depth: He's guilt-ridden, fighting himself. He's not gay, but he loves a gay friend and isn't repulsed. This situation recalls the genuine empathy of an unenlightened era (as when Brick protects Skipper's memory in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof).

When Pete's secret life as a habitue at a dockside gay bar is uncovered (Reggie is treated like candy there), we cannot help but feel for him as Reggie walks away, their friendship seemingly over. This is the filmmakers' good-hearted triumph. It is cowardly ("dodgy") Reggie who seems the bastard for not appreciating Pete's humanity. Until that moment, Pete was the best friend Reggie "ever had."

But despite Reggie's reaction, The Leather Boys still manages to show how the common humanity of gay and straight men--the essence of bromance--can be greater than sex.

I watched the Kid Rock Turning Point USA halftime show so you don't have to

Opinion: "I have no problem with lip syncing, but you'd think the side that hates drag queens so much would have a little more shame about it," writes Ryan Adamczeski.