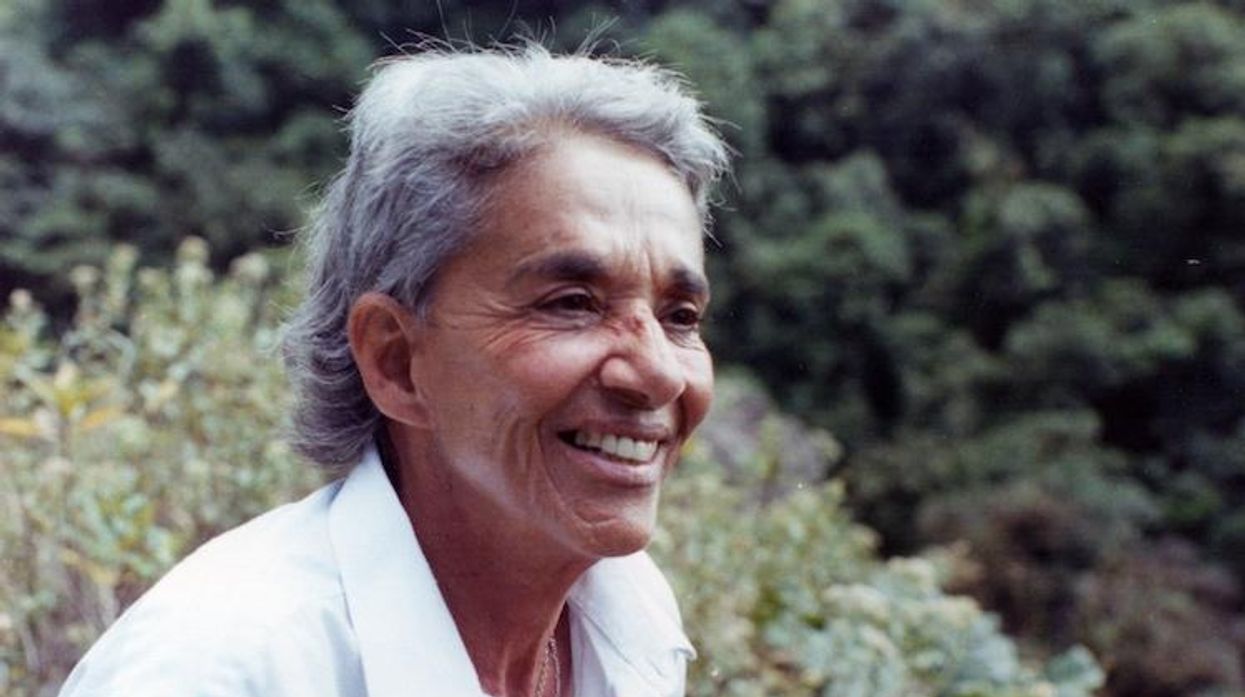

Our mothers and grandmothers loved Bette Davis and Joan Crawford in a different way than how the TV series Feud: Bette and Joan admits. At one point a gay male fan is told "What do you know about survival?" Strange and oddly resentful for show that devoted eight episodes--altogether the length of six classic Hollywood features--to the funk and fantasy of women's dressing room secrets. Feud's difference from Hollywood's vintage women's pictures may be generational, but it also measures a change in popular culture and gay male's sometimes confused attitudes toward women.

Showrunner Ryan Murphy, TV's leading gay mogul, conceived Feud to be a catty, mini-soap opera about rivalry and envy--not about artistry--and this turns Davis and Crawford's heroic struggles into half-comic travesty. Murphy's diva-identification has a tabloid nature. The show's surface admiration of women who are strong and talented and emotional soon diminishes those qualities so that they more closely resemble the vulnerabilities that gay men once shielded about themselves--specifically through the armor and vicarious pleasure of movies in which society's female underdogs dealt with men and cultural restrictions.

In Feud, the great divas get brought down to size. Bette and Joan are shown as too human--not the larger-than-life icons whose portrayals of common experience made 20th century audiences (specifically women, but also gay men) feel that their own desires and struggles were embodied by glamorous, magnetic personalities and then apotheosized.

Related | Ryan Murphy Interviews Jessica Lange on Fame, Feuds & the Feminine Mystique

Here, those aged, wrinkled, thick-waisted, over-made-up and petty Oscar-winners are leveled to meet the TMZ-era's degraded fascination with celebrity. Davis and Crawford are played respectively by Susan Sarandon and Jessica Lange, seemingly just because they are also past their Oscar-winning prime. Throughout, Sarandon's Davis strikes the iconic Margo Channing cigarette pose of All About Eve (1950) while Lange's Crawford disastrously distorts Faye Dunaway's brave and magnificent portrayal of Crawford in Mommie Dearest (1981).

Murphy's own careerism (seen in the TV hits Glee, American Horror Story, Nip/Tuck, The People Vs. O.J. Simpson) competes with the Davis and Crawford legends. Their combat, seen in relentless flashbacks, is a finicky jumble of Hollywood history. It misrepresents the picture-making process according to the fabled ugliness of studio-era exploitation (Jack L. Warner in another inauthentic Stanley Tucci performance) that made chumps of unempowered men as well as women.

Old Hollywood history may be remote for many in today's live-streaming audiences, so Feud compressed it. Several levels of nostalgia, fantasy and gossip intersected. Feud's cat-fight narrative measures the temperamental distance between the past and present. This fan's version of diva history departs from the affectionate derision of such drag artists as Charles Ludlum, Charles Pierce or John Epperson (Lypsinka). Instead, Murphy and his team of for-hire writers, directors and co-producers promote something new in gay diva appreciation. They perpetuate the same aberrant sarcasm that denied the serious intentions behind the movie Mommie Dearest, as well as Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (Smart-ass fans also demeaned Paul Verhoeven's Showgirls in a similar cultural anomaly that some gay men have come to rethink).

Our mothers felt no embarrassment about their emotional (and aesthetic) responses to Davis and Crawford, but modern snark makes emotion seem unacceptably vulgar. Davis and Crawford's personal intensity--unabashed displays of feeling and suffering--certainly lost glamour as they aged; they came to look merely desperate. But Feud doesn't know what to do with that desperation except pity it.

Related | Gallery: Jessica Lange is Joan Crawford in Ryan Murphy's Feud

Scenes of decrepit, lonely Crawford filming Trog (formerly titled The Missing Link) can't settle on scorn or mockery. Murphy's insensitive, TV vulgarity is like throwing shade at a bar--as a cover for his own insignificance.

Feud's biggest offense is to emphasize scandalmongering over art history. Second-tier actor Alfred Molina degrades the admirable film director Robert Aldrich, while others make famous Hollywood figures unrecognizable or worse--Mario Diaz is relegated to portraying what the credits identify as "a gay."

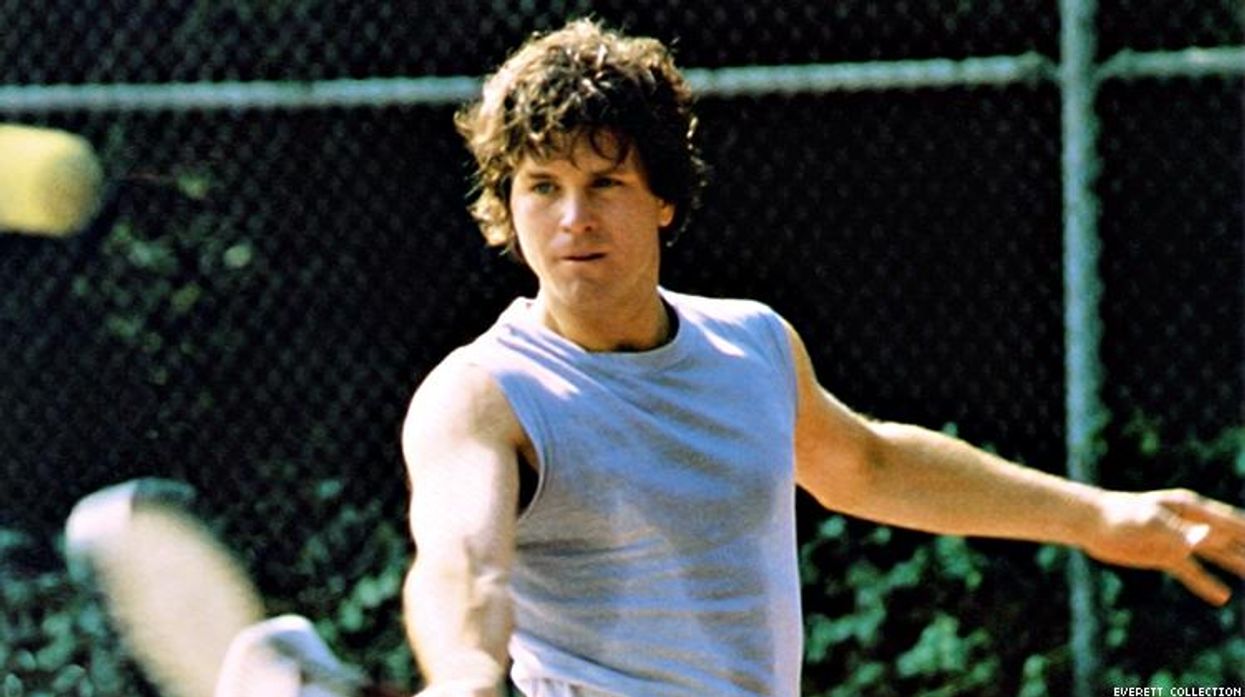

Feud takes for granted Davis' legendary iron-willed characterizations in That Certain Woman, Jezebel, Dark Victory, The Letter, Now Voyager and totally ignores the evolutionary stages of Crawford's screen femininity from thoroughbred thirties shopgirl in Sadie McKee to her strong, varied forties womanliness in A Woman's Face, Mildred Pierce, Daisy Kenyon and then the galvanizing Johnny Guitar.

By exploiting these legends, Murphy ignores what our mothers instinctively understood about womanhood. He seems embarrassed by Davis and Crawford's summit meeting on Whatever Happened to Baby Jane (1962) and so misreads for camp what director Aldrich presciently knew to exaggerate about his stars' desperation. Murphy's dependence on grotesque legend ultimately diminishes Baby Jane as a horror comedy when, in fact, the final beach scene up-ends grand guignolto create one of the most profound movies ever produced in Hollywood about family dynamics: two siblings' egotism yields to forgiveness--too late for the damage done to each other. It's a Tennessee Williams concept in Hollywood drag.

Let's uncomplicate this: Davis and Crawford were movie stars before stars were required to be role models. Our mothers's admiration differed from the adoration that gay men felt and expressed in the context of camp which only feigned distance from vulnerability while actually paying tribute to it.

The ugliness of Murphy's American Horror Story seeps into Feud's twisted ideas of femininity acted out by inadequate or miscast actresses (Catherine Zeta Jones as Olivia DeHavilland, Kathy Bates as Joan Blondell, Judy Davis as Hedda Hopper, all preposterous). This is cinema illiteracy at its worst, almost parasitic like the Lea Michelle's Streisand impersonations on Glee.

The force and personal integrity that Faye Dunaway ingeniously brought to Mommie Dearestdissolves into Lange's druggy pathos. Lange plays Crawford hideously, like the dope-fiend Mary Tyrone in her Broadway turn Long Day's Journey into Night (but, here, unforgivably scored to "The End" by The Doors) and this is Feud's ultimate betrayal. The virtues of sacrifice and self-discipline are foreign to this Movie Star Lives Matter weepie. It entombs Old Hollywood's female warriors in misery as pathetic creatures--the last thing mothers want their gay sons to emulate or celebrate because it debases that vital connection.