This article originally appeared in the June/July 1993 issue of OUT.

Your video display terminal is a battleground. Your weapon is a modem. Your ammunition, electronic mail. On computer bulletin-board services, you rally the troops. You drop in on several "electronic cafes," where dozens of queers exchange news, information, and instructions. Within minutes, you've let scores of people in on your plan; in turn, each of them has passed it on to scores more. Then, with the push of a button, you and thousands of others launch fax zaps, mail zaps, and phone zaps, bombing your enemy with a continuous stream of raw data, printed messages, and recorded voices. Instantly, you're taking to task a newspaper that printed a homophobic article, a member of Congress who refused to sign on to a pro-gay bill, a religious zealot who preaches hate from his pulpit, and a corporation that hasn't expanded its bereavement-leave policy to include gays.

Press another button and you receive your customized electronic newspaper. All the news about gay issues and your other favorite topics from gay and mainstream newspapers around the country and the world is downloaded onto your screen. You punch in a code and get your own personalized AIDS updates, complete with current information on drug research and drug trials.

"We already have an edge over the religious Right in terms of utilizing this kind of technology," says Tom Rielly, director of strategic relations at SuperMac Technology, a maker of computer hardware. Rielly sees the above scenarios taking place in the not-too-distant future. "When it comes to setting trends, queers are always at the vanguard, and the computer revolution is no different."

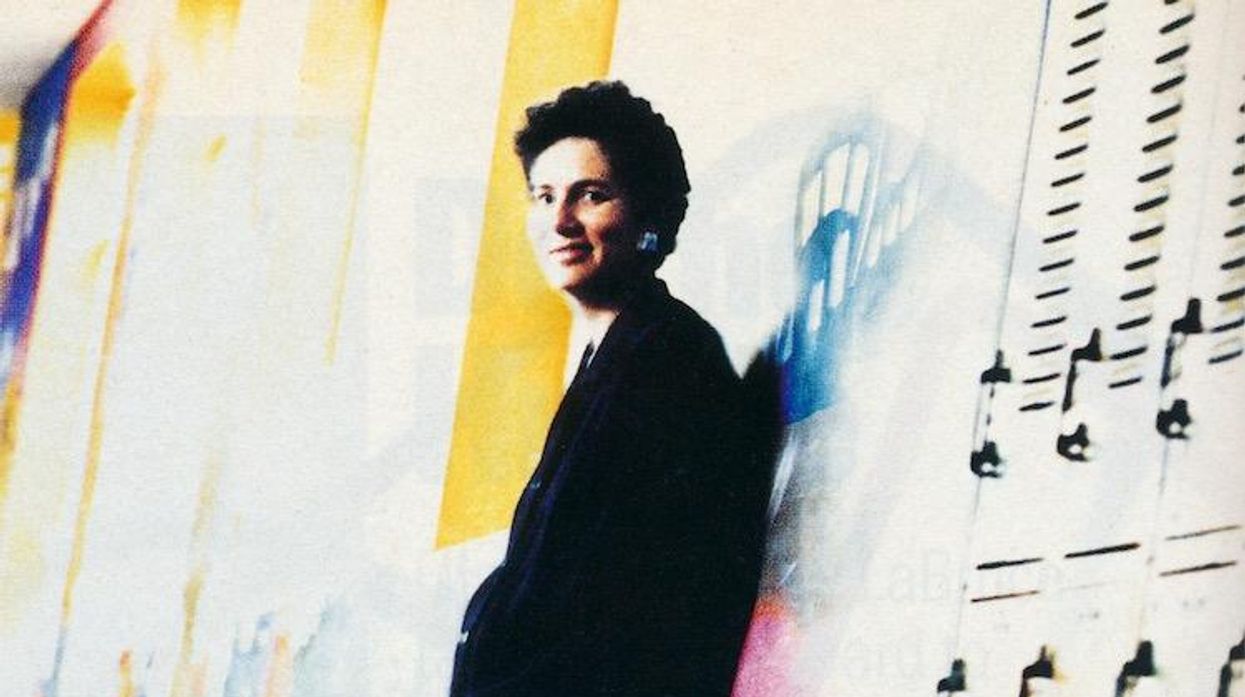

Over the past few years, gay and lesbian activists, perhaps more than other activists, have been remarkably adept at developing and utilizing advances techniques to take on the system. "It all started with ACT UP," observes Susan Schuman, a lesbian who is manager of communications products for Apple Computer's Personal Interactive Electronics division. Apple, like SuperMac, is located on the peninsula in Northern California between San Jose and San Francisco known as Silicon Valley, the center of the personal-computer industry in America. Schuman is a telecommunications expert who has been in the field for over 12 years.

"People have different thoughts on ACT UP, but ACT UP was very smart," she says. ""They used technology-- satellite transmission, fax, computers. They organized around manipulating and managing the media and excelled at the transfer of information back and forth. Now a whole new younger generation of more out gays and lesbians in coming up, and they're going to be even more technically literate."

According to Overlooked Opinions, a Chicago based market research firm, 10 times more queers work in the computer industry than in the fashion industry. And unlike their brothers and sisters in the older industries of Hollywood and the New York media world-- and certainly unlike those within Washington's political system-- queers in Silicon Valley are much less likely to be locked in the closet. They are visible, organized, and highly productive.

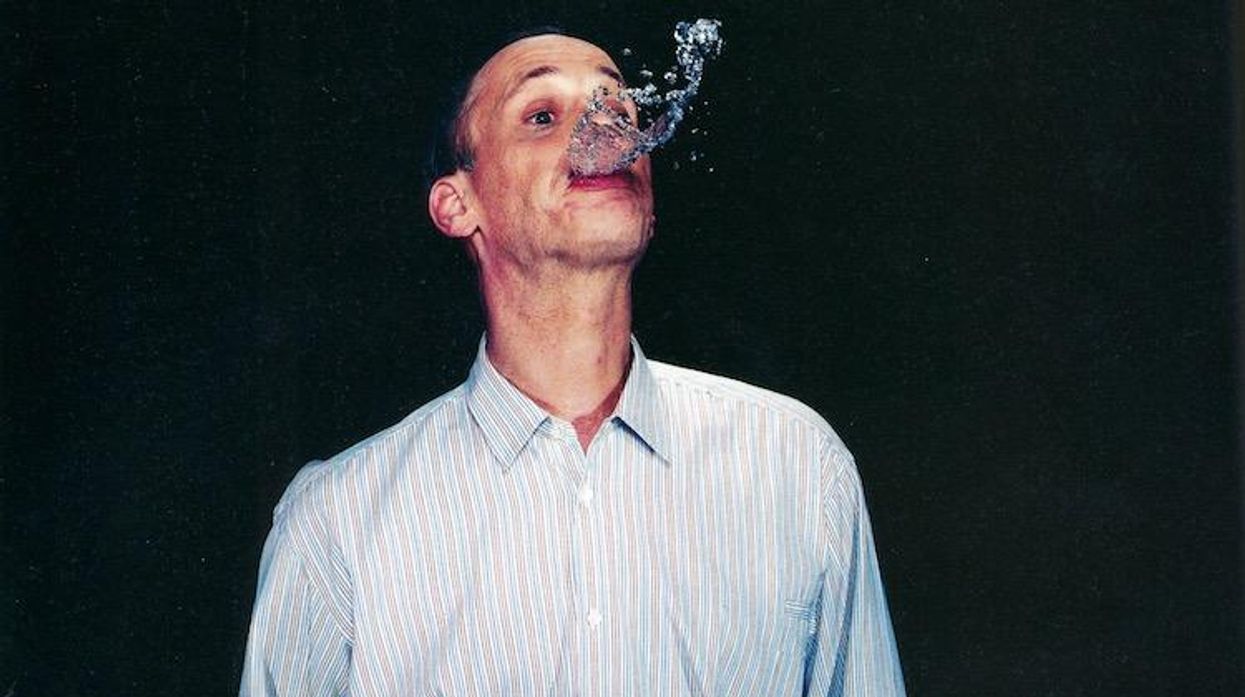

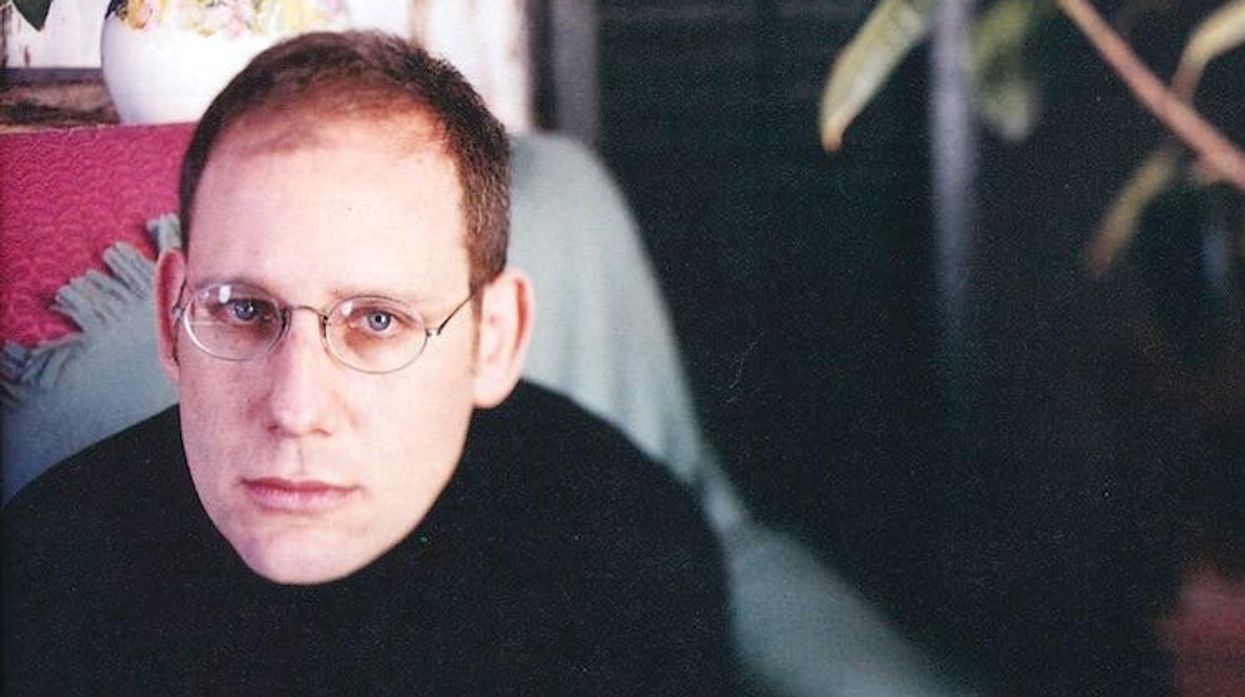

In high school, Jonathan Rotenberg was very interested in computers. That was in 1976, when few people knew much about them. "I had heard about these new microcomputers that were coming on to the market," he remembers. "So I inquired about them." A few months later, at the age of 13, Rotenberg founded the Boston Computer Society, a group dedicated to helping people learn about the personal computer at a time when this technology was completely alien. Within a year, the society experienced a 300 percent growth in membership, from 10 people to several dozen.

But that was just the beginning. The computer industry began to explode as the '80s began. Heading the society-- whose membership would top 31,000 worldwide-- Rotenberg became a teenage CEO and was soon internationally famous. By the time he was 19, he was on the front page of The Wall Street Journal and was named one of the 10 most eligible bachelors in Boston by The Boston Herald.

Throughout all that time, Rotenberg was completely in denial about his homosexuality-- or any sexuality; he poured all of his energy and time into computers. He didn't have sex and didn't really fantasize about it either. "Every once in a while, I'd get concerned about it," he says. "I thought I was awkward and not polished with women and thought that it would just happen someday."

It wasn't until years later, in 1990 at the age of 27, that Rotenberg came to terms with the fact that he was gay. That was after a lot of soul-searching and years of therapy, and after he entered Harvard Business School.

"I looked around the class one day," he says. "I realized that people my age were starting to look older. I realized that I wasn't going to have my youth and vitality forever. So at that point I decided to call the president of the Gay and Lesbian Students Association." Rotenberg's plan was just to "explore." He was an "uncommitted."

"Their meeting was the first gay anything I ever went to," he says. "Within 30 minutes, there were all of these people who were saying, 'He's the president of the computer-society.' There were actually three members there. I felt comfortable."

Today, Rotenberg is a corporate strategy consultant in Cambridge. Looking back, he observes that he was forcing himself to suppress his sexuality by escaping. "I wasn't allowing myself to feel these things," he says, "and was putting all of my energy in the society and computers.

"I think in general you find much greater diversity of people at all levels of the computer industry, especially in personal computers, than in other industries," he observes of Silicon Valley. "It's a new industry and doesn't have any of the baggage and the old-boy networks that are very integral to other industries."

Queers in the computer industry are quick to point out that Silicon Valley is by no means a utopia. It is, like the rest of corporate America, a predominantly straight, white, male industry with a glass ceiling when it comes to women and minorities. "There's more of an effort in this industry to exhibit some consciousness," says Bryan Simmons, a black gay man who is manager of corporate public relations at Lotus. "It is a younger industry , but it's still mostly white and mostly male. There's the same amount of racism here as throughout society. I think it is still difficult for someone who is openly gay, or black or a woman, to become a senior executive in these companies."

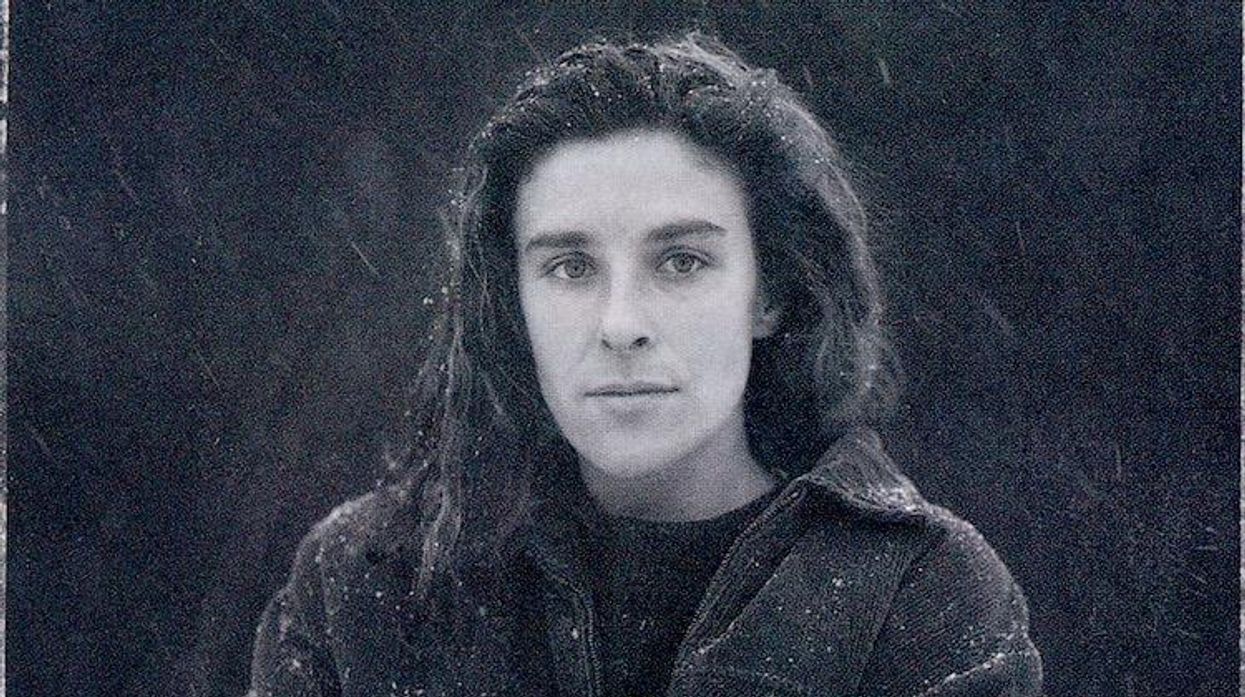

"I would say there are pockets in the industry that are much more tolerant," says Schuman, "but there is still a closet." She also feels that the industry is far from treating women equally with men-- and that includes lesbians and gay men. "This industry might not have an old-boys network but it has a young-boys network," she notes. "There's also a male network as opposed to a female network, especially among gays." Shuman says that gay men, often comfortable in the industry, still treat lesbians the way straight men often treat women. "I've seen instances where people, because they're male and gay, moved up," she says. "There's sort of this split of the sexes that goes on with gays. And there is a glass ceiling for all women."

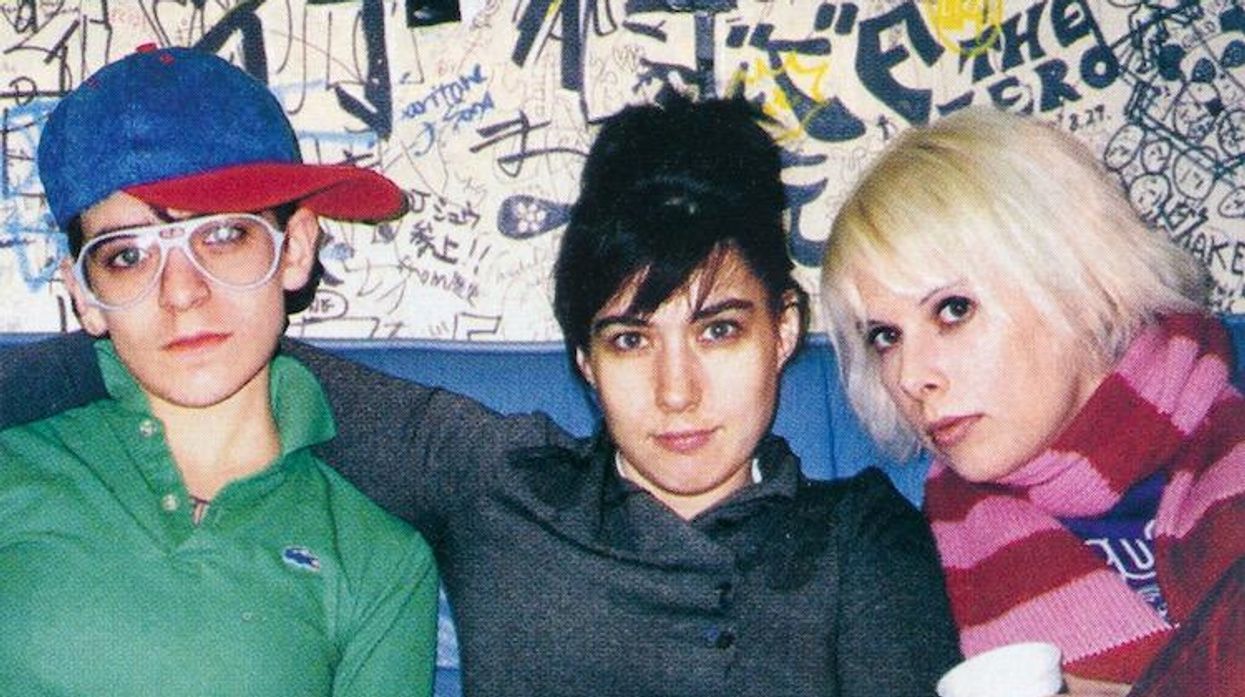

Karen Wickre, who works at multimedia developer 3D0 in San Mateo and co-founded Digital Queers, a group of lesbian and gay industry professionals, agrees: "It seems like there are a lot of gay people, but it's a very extensive gay male network-- not as many lesbians. The lesbians just aren't as networked and organized. They also seem to be left out by the men." Yet Wickre notes that women, in general, probably do better in this industry than in others. "There are a lot more women in power," she says. "I think it's probably easier attain that power here."

Though problems exist, queers of both sexes, especially those who've worked outside the computer industry, agree that theirs is a more comfortable place to work than others. Some of those who do gay organizing in the industry also feel that if it weren't for the tolerance of the industry-- and, more important, the easy access to technology-- they might not be involved in political issues at all. Some people are even encouraged by their bosses to use their jobs to advance gay rights.

Jeff Pittelkau is a laboratory director at MacUser magazine and another Digital Queer. "I was basically outed in from of a former boss years ago by a colleague," he says. "My boss was very accepting and asked, 'Why didn't you tell me?' A couple years later, I had another boss who I spoke to about whether or not I should move into another position, my current one, because it's very public in terms of interfacing with vendors who make many of the products we evaluate. He advised me to take the job, saying: 'This is a rare opportunity for you to use your position in the industry to stand on a soapbox for gay rights.' I was astonished."

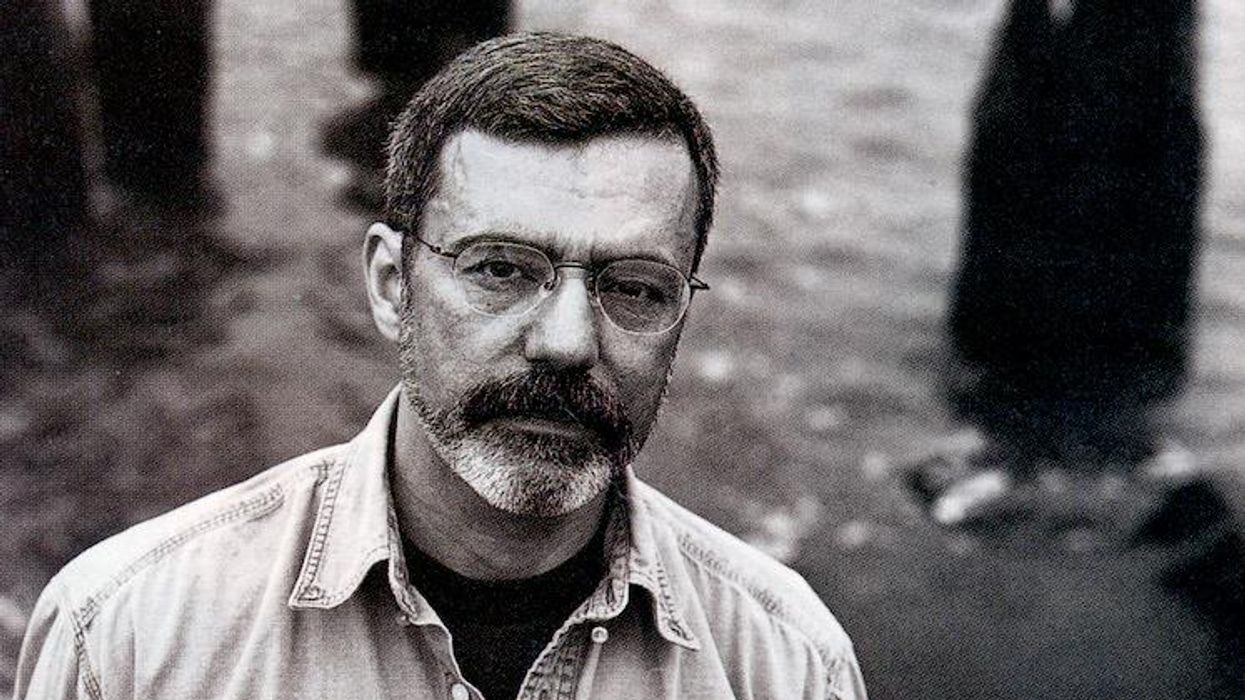

Unlike the rest of the business world, where discretion is thought of as the better part of valor, the computer industry fills some of its highest positions with gay people who are out of the closet and politically active. Tim Gill is the founder, senior vice president of research and development, and chairman of Denver-based Quark, Inc., makers of QuarkXPress desktop publishing software. In November 1992, he was an outspoken leader in the fight against Amendment 2, the antigay measure put on the ballot in Colorado. He was the largest contributor to the anti hate campaign. In the fight to overturn Amendment 2, Quark pledged $1 million toward education efforts. Gill also led a boycott of the state, telling his own customers that he understood if they had to participate in the boycott. By threatening to pull $20 million in accounts, Gill forced one of Quark's banks, Norwest, to immediately institute a gay-inclusive nondiscrimination policy in the wake of the vote.

"I was an introverted kid--even before I knew I was gay," Gill recalls. "Being gay tends to make you introverted. I think that, for me, the computer was a little world all its own-- all of a sudden this world and everything in it could be mine. I could control it, and certainly there's a tremendous feeling of power that gives you, especially if you feel powerless.

"Because the industry in Northern California-based, near San Francisco, a lot of gay people work in it, and the political climate of the entire area is liberal," he says. "It's a younger industry and more tolerant. But also there's a desire for talent, for the best people. The problem with discrimination in hiring is that you lose people. The computer industry has fewer talented people than it needs. Nondiscrimination is a way that you keep a higher number."

"It's a real renegade industry that had prided itself on breaking the rules, " observes Wickre. "The business itself broke the rules in the way it grew and developed. It's this sense of progressiveness, of not doing business as usual, that has affected a lot of personnel policies and human resource departments of the companies here."

Over 50 Silicon Valley companies, including Apple, Deck, Tandem, IBM, Oracle, and Intel, have policies banning discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Almost all of them make The San Jose Mercury News' annual list of the top 100 companies in the area. As of 1992, domestic-partner benefits are being instituted among companies in the computer industry faster than in any other industry. That is true not just among Silicon Valley companies, but throughout the industry. Boston-based Lotus became the first to offer domestic-partnership benefits. It was followed quickly by Borland, ASK-Ingres, Silicon Graphics, Sybase, and several others throughout the United States. "There's the high-tech industry in Silicon Valley, which is very close to San Francisco and the Bay Area, which is a huge gay population," observes Schuman. "And then there are technology focal points in the Boston area, the New York area, and the Washington and Chicago areas-- all large metropolitan areas for gay people." Each of those cities has computer companies that have instituted or are negotiating domestic partnership benefits for gay employees.

"It's now about competition," says Jeff Bowles, a manager in engineering at ASK-Ingres, a maker of database software. "Nobody wants to be beaten out by the other companies, especially since they're afraid that all of their talented lesbian and gay employees will leave a company to get better benefits elsewhere."

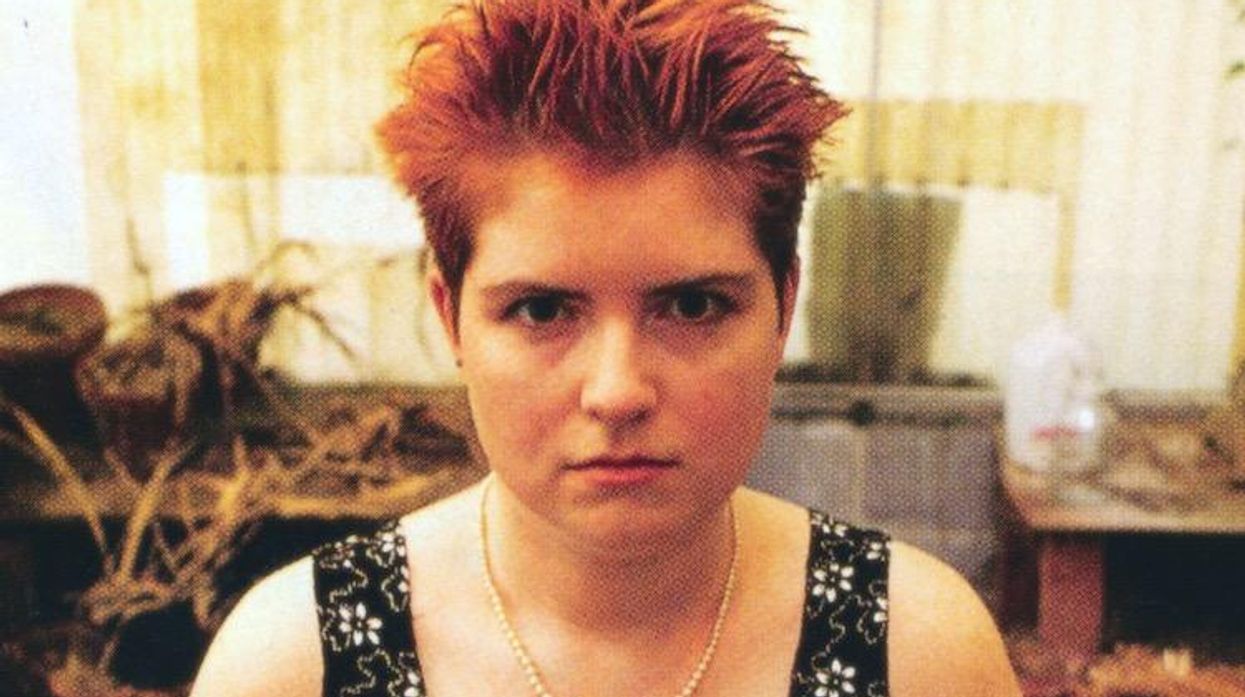

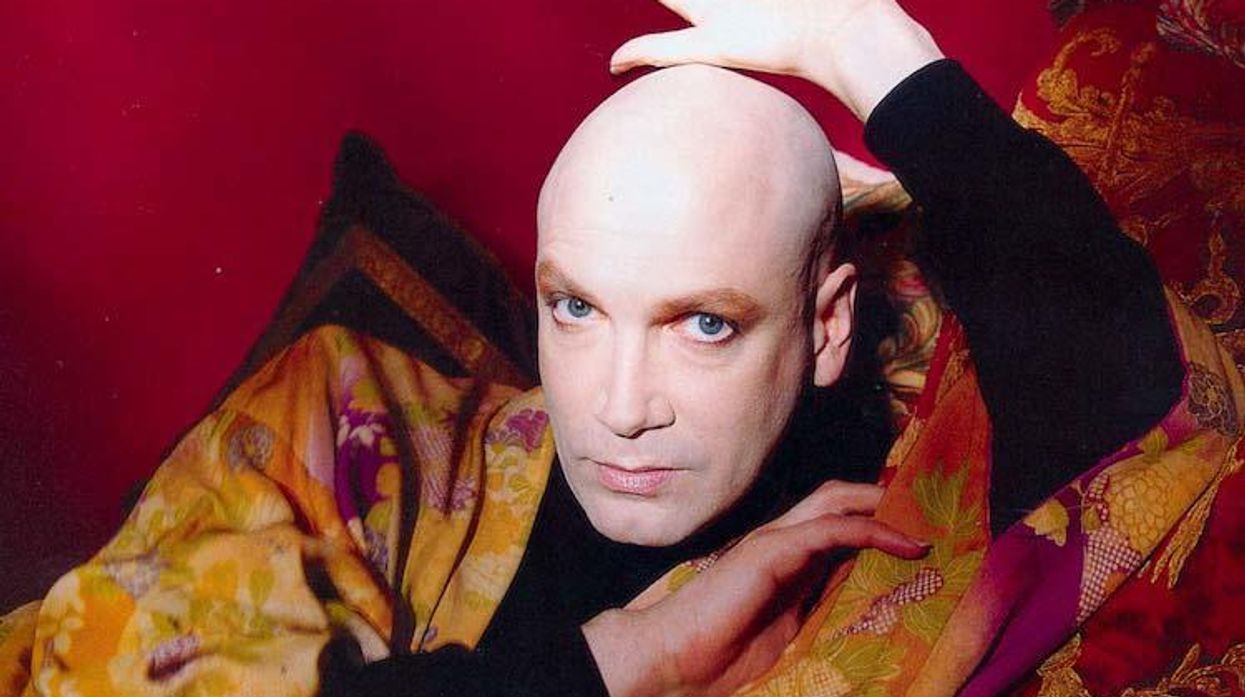

Digital Queers was founded in 1992, when Tom Rielly and several of his friends began having informal social gatherings. Rielly is a dynamo among dynamos-- confident, poised, and determined to enlist advances high technology in the pursuit of gay civil rights. He wasn't always so confident.

"In high school, I used to stand in front of the mirror with a razor blade and chant, 'If you are one of them, you have to kill yourself,'" he recalls, describing his personal motivation for activist work today. "I finally did try to kill myself three times, overdosing on drugs. I just don't want any more kids to kill themselves. I want to make sure that accurate information gets to kids in the fasted way possible."

For Rielly, it's imperative that the entire movement become computer literate, speeding up communication. In January of this year, he and Digital Queers organized an unprecedented benefit forthe National Gay and Lesbian Task Force during the Mac World Expo in San Francisco, one of the largest computer trade shows, bringing together 75,000 people in the industry twice annually. Before the benefit, Rielly and Pittelkau went from booth to booth soliciting software to present to NGLTF at the benefit. "It was astonishing," says Pittelkau. "People were just handing software over to us. We explained what Digital Queers was and what the NGLTF was. The fact that they were gay organizations didn't faze anyone. They were more interested and excited about the fact that we were switching NGLTF over to the Macintosh system." Four hundred people showed up for the benefit, which took in $50,000 in cash. Over $75,000 in computer software and $75,000 in consulting services had also been donated to the NGLTF.

"That benefit in San Francisco was that start of something big," says Elizabeth Burch, senior litigation counsel for Apple Computer (worldwide). "It was seeing people like Tom Rielly speaking-- a true technoqueer, someone who loves technology and loves his people. And it was seeing all of these gay high-technology people in a room together for the first time." Birch, like Rielly, combines her unique skills as a legal and high-technology professional with political activism. The highest-ranking openly gay person in Apple's corporate hierarchy, she became co-chair of NGLTF's board in late 1992.

Birch sees the growing power structure of Silicon Valley eventually influencing and changing the Hollywood power structure. "You see this technology now seeping into the entertainment industry and you see this cross-fertilization," she observes. "This is because in the future, beginning in a very significant way in the 1990s and completing in the 21st century, entertainment and high technology will comingle. Entertainment will be computer-based and the software will come from Hollywood. What you will have is a situation were HOllywood will also adopt the values of this industry, in terms of the way they treat the work force--instituting enlightened policies, because they will be the only policies under which the high-technology people will work."