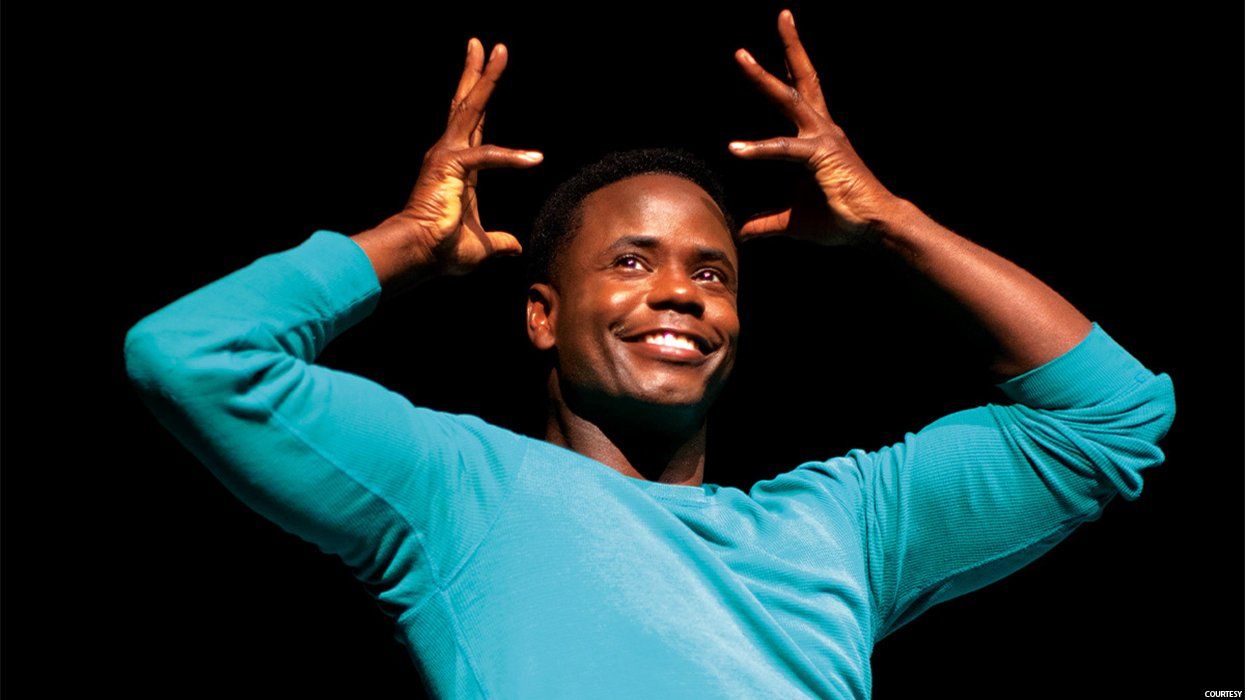

FLEXN Photo by Stephanie Berger

It's about 10 miles from the Upper East Side in Manhattan, which lines Central Park, to the East New York neighborhood of Brooklyn, which borders Jamaica Bay. Economically and ethnically speaking, they represent opposite ends of the city's demographic spectrum. This week, the Park Avenue Armory, a large, stately venue living in the former location, presents FLEXN, a performance featuring dancers and a dance style largely born and raised in the latter. It's a cultural exchange as stark as if the artists where coming from China, but really, it's just the two halves of New York facing each other, which feels revolutionary - and potentially problematic, at risk of exoticization.

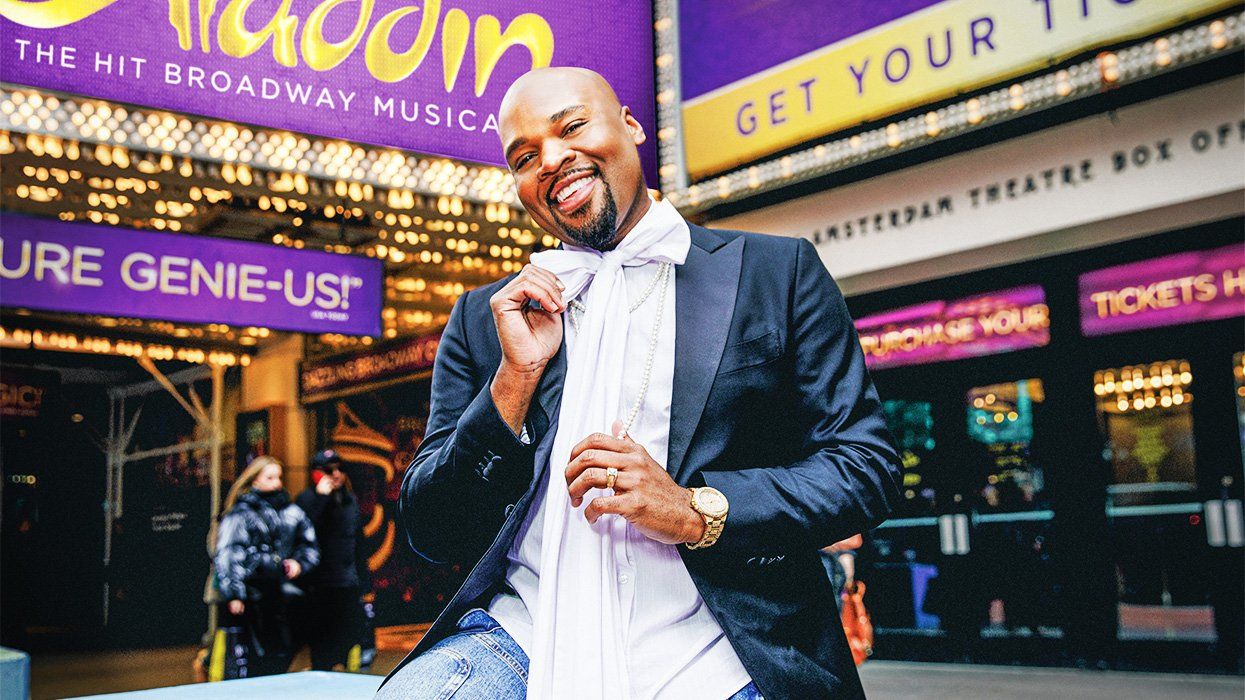

FLEXN, which runs March 25 through April 4, smartly neutralizes some of that risk by enlisting co-directors representing each world: Reggie (Regg Roc) Gray, a flexing pioneer, teamed up with celebrated avant-garde director Peter Sellars to create a unique theatrical experience that honors flexing's roots, showcases some of its top practitioners, and plants it firmly in the current, complicated national dialogue around race relations and law enforcement. But before flexing became a vessel with which to address social inequality, it was simply a mode of physical and psychological expression that evolved from a convergence of roots.

Gray was around 5 years old when he started dancing. "I was doing my dancing thing, my Michael Jackson stuff," he tells Out. Born in East New York, Gray grew up partially in Alabama, where books and sports occupied most his time. It wasn't until he moved back to Brooklyn, in 1997, that dance became a bigger part of his life. "That's when I started picking up the dance hall Jamaican reggae roots, the culture of Brooklyn at the time," he recalls. "It attracted me, the reggae beats, the feel of it. You see a lot of dancers getting a lot of the girls at the time, so I was like, 'Let me get some of that too,' " he says with a laugh.

Throughout the '90s, Gray recalls, the culture of Brooklyn was an exciting creative community, a vibrant stew of dancing, rapping, singing. In 1999, he and his friend Nugget (many flex dancers go by one-word nicknames) were at a show and, as Gray puts it, "we did our thing and then there was no turning back."

Their "thing" was a variation on bruk up, a forceful, rhythmic twitching dance that can be traced to the clubs of Jamaica in the early '90s. The two each stamped the form with their own style; Gray calls his "pausing," a sort of stop-action animation that came about almost by accident, thanks to a television.

"Me and my friend used to watch ourselves on the VCR and rewind ourselves and try to do stuff backward," he says. "I pressed pause on my VCR and [saw] this glitchy thing. I was like, 'Yo, I want to dance like that.' " The resulting visual effect -- akin to thumbing through a flipbook -- has become a recognizable staple of flexing. Other components include gliding (think of the flow of moon-walking but on a more maze-like path), Bone Breaking (extreme arm distortions that give flexing an almost grotesque beauty) and hat tricks, which involve some genius sleight of hand. Underlying all this is the sense of a story unfolding; often the most compelling flexors are those that appear to transform into characters.

The style took off, gaining followers and innovators. Battles pitting dancers against one another became popular community events. Crews were formed, incorporating choreography and theatrical drama (Ringmasters, a flexing crew from Brooklyn, brought in new fans after appearing on the TV dance competition show America's Best Dance Crew in 2009.) YouTube videos went a long way in attracting attention.

The 2013 documentary Flex Is Kings brought wider visibility to the form, and captured the seriousness with which flex dancers approach their craft and the tight community that has grown around it. The film follows preparations for a Battlefest and several aspiring competitors. Among them is Flizzo (Jermaine Clement), an intense powerhouse for whom flexing seems to be an escape from internal turmoil, and Jonathan George (known as Jay Donn) who is recruited by a contemporary dance company to put his moves to work as the title character in an artful retelling of Pinocchio, which ultimately premieres at the prestigious Edinburgh Festival.

That dual snapshot of flexing as both a raw, personal language of the street and a physical dialect that can be applied in a more theatrical context informs FLEXN at the Armory. More than 20 flex dancers are featured in the show, which includes both set choreography as well as the improvisation that makes flexing such a surprising, and surprisingly moving, style. "As a flex dancer, we dance from our emotion, we dance from our feelings," says Gray. "It's unexplainable. It's something inside you that you feel. Free-styling is so personal to yourself and who you are."

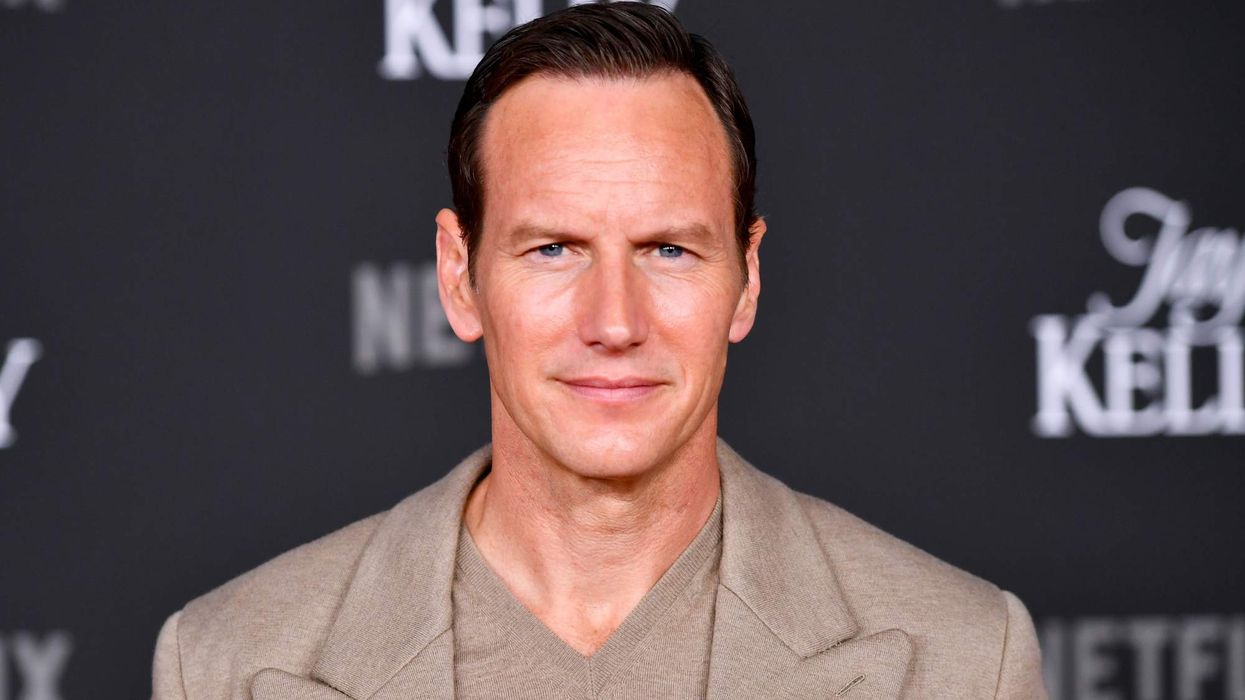

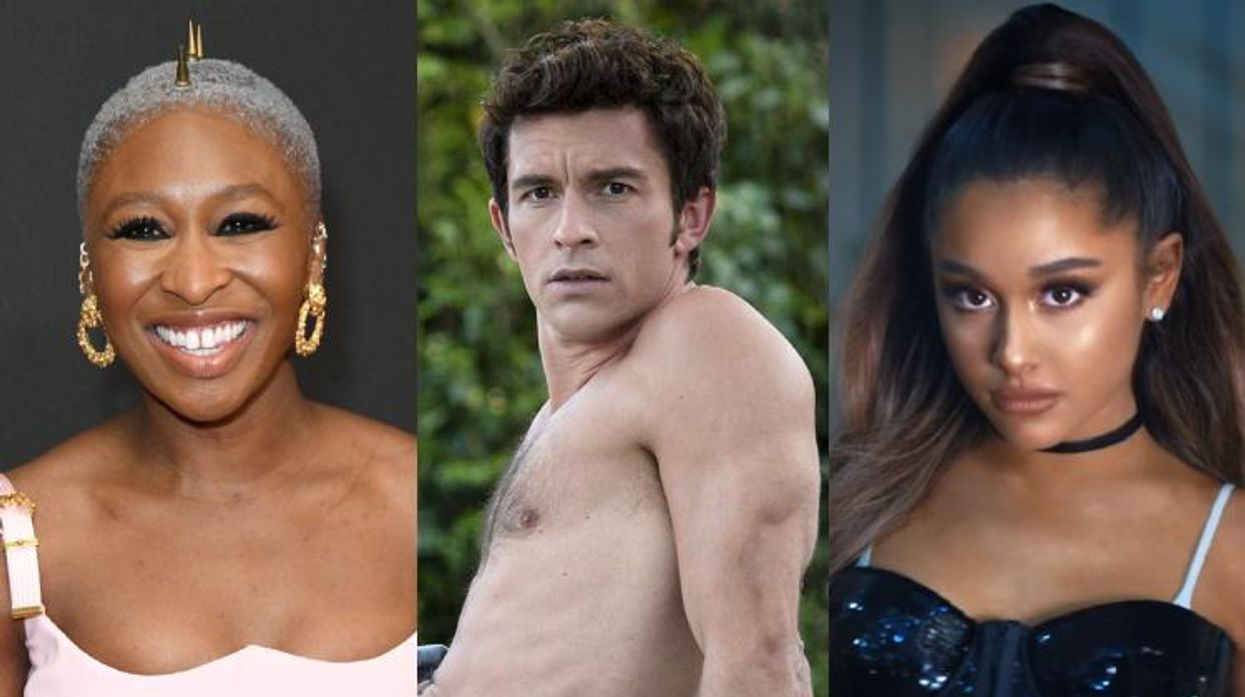

Reggie (Regg Roc) Gray & Peter Sellars

But flexing also reflects the broader social experiences of its pioneers and pros, which sometimes involves stylized references to violence and loss, a layer that can make flexing unsettling to watch. It's this shadow that co-director Sellars wanted to explore further, which led to the development of pre-performance conversations with noted writers, academics, politicians, law enforcement officials and activists about the difficult issues of the day. At 7 p.m. before each show, audience members can engage in conversations like "Profiling Stop & Frisk," "Reforming Rikers" and "College or Prison?"

That's a bold and possibly uncomfortable way to begin an evening of dance. But it also rightly and importantly connects the dots between personal expression, communal culture and national social issues. Gray credits Sellars with pushing that point in this project. "[Sellars] came with the idea of juvenile injustice, how we can speak to a community of people who don't see and understand what happens inside the prisons and the court system, the political side of the situation."

Gray points out that flexing has a long tradition of addressing politics, so when Sellars proposed this angle, "I was like, 'Hey, that's right up our alley." But for Gray, FLEXN is also an opportunity to share his culture with fellow New Yorkers who, despite living just a few miles across town, have little to no understanding of it. "Flexing can speak to anyone," he says. "It's not a fashion, it's been brewing in Brooklyn for some time now. This comes from the city where we live. It's beautiful."

FLEXN at Park Avenue Armory in New York City through April 4.