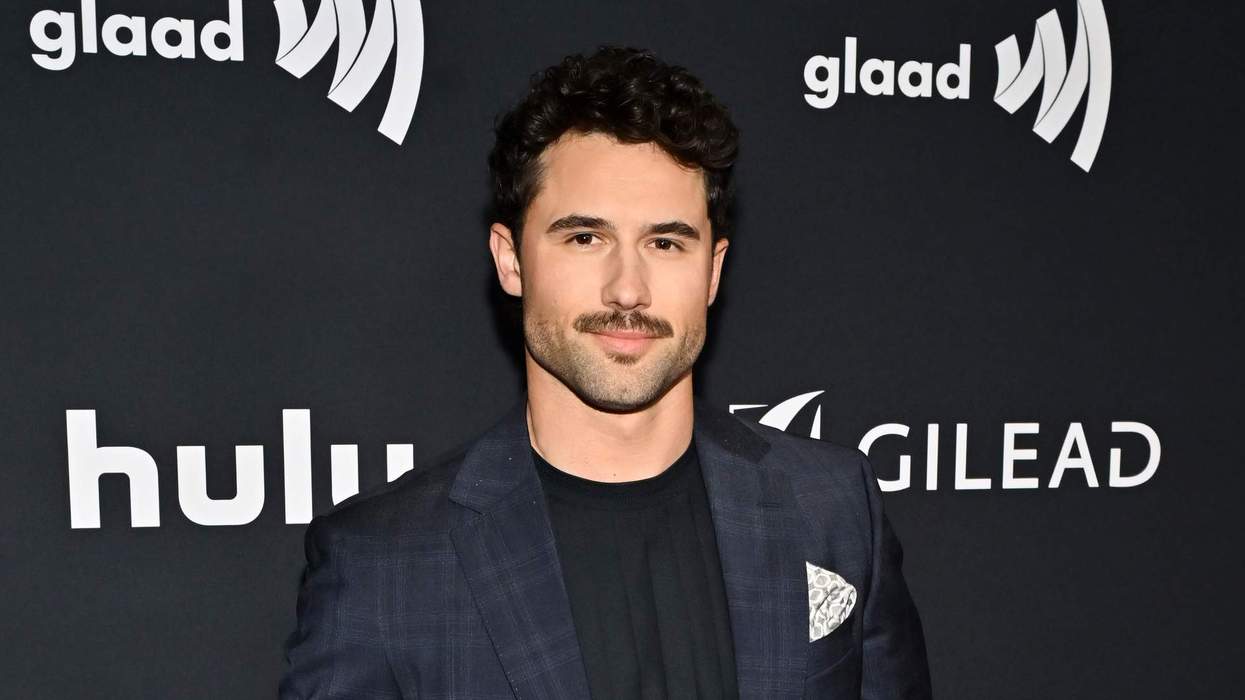

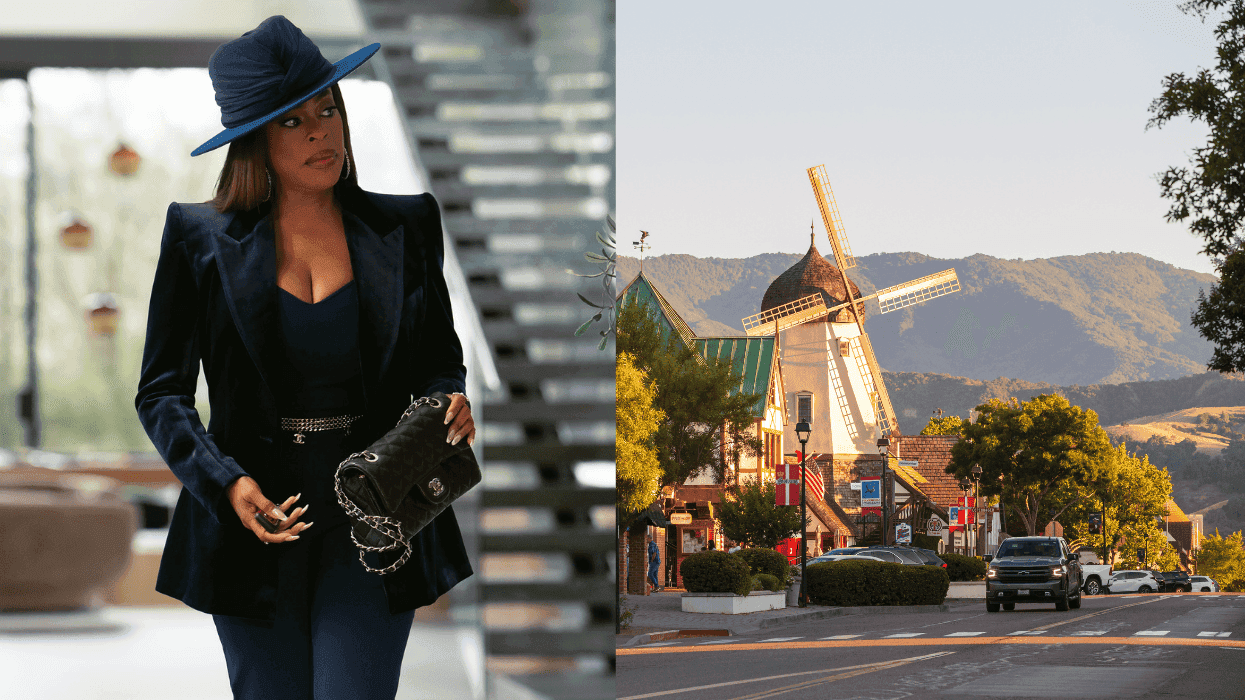

Photo courtesy Ibru Yildiz

For a quarter century, since the publication of the seminal queer theory text The Queen's Throat, Wayne Koestenbaum has been one of our leading gay cultural critics. Alongside his parallel careers in poetry and the visual arts, Koestenbaum has been responsible for some of the most penetrating and haunting literature on queer identity, subcultures, and fixations.

When The Queen's Throat was published in 1993, it was lauded by the likes of Susan Sontag and immediately provoked ardent discussion. In it, Koestenbaum dissects at length the centuries-old phenomenon of opera superfandom among gay men, long referred to as "opera queens." Koestenbaum concocts gem after gem in witty, deeply personal chapters like "The Callas Cult" and "The Codes of Diva Conduct," while offering a poignant elegy for a generation of devotees recently decimated by AIDS.

OUT contributor Austin Dale sat with Wayne to discuss the book's legacy, the current scene of opera queendom, and why Youtube has improved his life.

Austin Dale: I want to talk about The Queen's Throat twenty-five years on, and about the current state of queer opera culture, which I'm a part of, but I'm coming into it very late. There's a sense in which I missed the party, or at least I feel that way.

Wayne Koestenbaum: I would console you by saying that I felt in 1980, when I joined the party, that I was fifty years too late. Everyone who joins the party feels like they arrived late. Opera is a belated art form. The second thing I would say to console you is that the feeling of belatedness is a great passageway to the melancholy and queer paradoxical state of embodiment and disembodiment that opera at its best can offer you.

So hug your belatedness. Savor your sense that the golden age of opera queendom is over. I talk a lot in the book about the death of opera. Opera has always been dead and always been about resuscitating the dead. You're right in step with opera's crucial themes.

AD: My other lament has been that you're never in the right city for the right thing. And if you want the commitment of devotedness, you have to be ready to travel.

WK: I was born in San Jose, California. The San Francisco Opera is a magnificent thing, but between my birth and age eighteen, I went once to the opera, so I might as well have been in Boise or Akron, though I'm sure parenthetically that Boise and Akron now both have thriving opera scenes. Even though I was near the right city, I was in the wrong city.

I've been to Venice several times. The first two times I went to Venice I couldn't even get near the opera theater, and the third time I went to Venice the opera had burned down! I'm going for my birthday this coming year, and I'm finally, finally going to be able to see the opera in the Teatro La Fenice, so it's kind of a lifetime dream, the dream of finally coinciding, being in the right city at the right time.

AD: What are you seeing?

WK: On the night of my birthday they're doing Madam Butterfly, and then a few days later they're doing La Traviata, which, as you know, actually premiered at the Teatro La Fenice. They're both very old-fashioned operas at this point, but it's just as well that they're not doing Peter Grimes or something like that. With all due respect to Benjamin Britten.

AD: When people started telling me about The Queen's Throat, I had already been bitten by the opera bug. Opera had already become something that I needed.

WK: Oh, lucky you! Not that you got my book. How wonderful that you got the bug! How?

AD: Well, it's an acquired taste, so I had been chasing it, but then there's the point when something clicks, and you can't listen to any other type of music anymore, and for me, it was a live Traviata, the "Sempre Libera," and it was Callas.

WK: That shows your sophistication, because that's not the easiest way in if you're inexperienced. With a live recording there's a lot you have to forgive and imagine, because the sonic scene is so impoverished.

AD: That's true, but one of the things I always love about live recordings is that you can often hear the queens in the audience. That's my favorite thing in the entire world.

WK: And when you hear a particularly loud, queeny "Brava" that wants to be the first to erupt.

AD: I relate to that very much.

WK: There are a lot of great live recordings that I listen to on Youtube. And let me just digress by saying that you're not too late, because Youtube is better for queendom than anything in the history of opera. It's all there now. When I was writing The Queen's Throat, I could not have dreamt that I would one day have access to these performances. That I could hear a bit of Anna Moffo and Placido Domingo doing La Traviata, I think in the early 1970's? Learning that that even existed!

AD: I meet guys all the time that would probably lose themselves to opera if they found their way in. For example, lots of gay men are highly sophisticated about Broadway vocals. They have a firm proficiency in diva worship and the library science of diva cataloging. There's just some insecurity that seems to be holding them back. And even with the very smart queers, the type who are actually interested in knowing all the best and gayest things, if I say, "Oh, I can't do that Thursday, I have the opera..." they'll say, " Oooooh, the opera," like I'm being an asshole by even mentioning it, and it baffles me, because it's not like these guys don't, for example, love to go to art museums regularly, and stuff like that. But I figure, you know, you can't push it on people. Or can you?

WK: You just need to do an intervention, basically. You don't want to give them the whole apparatus at once. It would be too engulfing. Don't say Verdi wrote 32 operas, and don't even go near Wagner. I have had great success in lectures by just showing a couple of super glamorous, super dramatic clips. I remember one time, in a panel on how Youtube is changing art, at The Kitchen in New York, I showed a clip of Anna Moffo singing "Depuis le jour."

It has these gorgeous close-ups, and she looks beautiful. I have a painter friend who wasn't an opera queen, but he thought it was the epitome of glamour and he just went nuts. And so you just give them a hit single, a 45, three minutes of the whole package. It's like Frank O'Hara said about poetry: "I hate when people try to spoon-feed poetry to people. People don't need poetry." We don't need National Opera Month. Some people just need a timely intervention.

I do think it's a sixth sense, though. Clearly you and I discovered this thing on our own. I say in The Queen's Throat that I didn't really get into opera until college. Nobody said to me that I had to try this stuff. I just found it irresistible when I got to it on my own.

Some people have theorized psychoanalytically about, say, the soprano's voice on the psycho-physiological apparatus, and it is profound. If you think of Shirley Verrett's metzo or Birgit Nilsson. On the radio the other day I heard the Met broadcast a Birgit Nilsson performance of Salome from, I think, '65, with Karl Bohm. And I'm not even the biggest Birgit Nilsson fan, but I would imagine that physiologically, for someone in the audience, it would be an overwhelming, ineluctable experience. It's the lack of amplification. It's really those bodies producing that sound.

AD: That maybe helps me understand. But I do think that this sixth sense is a queer sense, perhaps something that results from the alienation of growing up queer, but as we become more assimilated into mainstream culture, queers have left opera behind. Opera queendom was never going to be part of mainstream culture, but I'm constantly thinking about queerness and its spiritual relationship to opera as we move into the future.

WK: They'll have new thrills. In the future, these people will rediscover the thrills that we had. Who knows where the culture is going anyway? Who knows which encampments of the future will have to reinvent civilization and have to reinvent opera? As a culture we are kind of on the Titanic, as I see it. The fate of opera and the fate of extreme pleasures like that is entwined with the fate of the earth. It's survived so much.

There's going to be some post-apocalyptic encampment where there will be an unbelievable contralto singing [from Il Trovatore, the role of] Azucena, walking around the wreckage, and there's going to be some wide-eyed queer eyes boy, or girl, or someone who's both, who is they, who is going to be following around Azucena as she sings by the campfire. And it will start completely over. There's always going to be a contralto, there's always going to be a soprano, there's always going to be a tenor, and the intensities of a trained voice are going to find a home. As long as there are throats and lungs and diaphragms and resonators and masks. The equipment is there.

AD: The Codes of Diva Conduct will be very different after the apocalypse.

WK: Yes. But there's still going to be rivalries, and cataloguing. We're of different generations, but we're both on the Titanic, leaning over the rail, and we're watching empires collide, and we're seeing ice floes crash into each other. What would you choose as the background aria for this scene in the movie?

AD: Oh! When you talk about ice, I immediately think of La Wally. Doesn't the soprano throw herself into an avalanche at the end?

WK: Oh, of course, perfect. Actually, speaking of that aria, it was the movie Diva that got a lot of people into opera. I heard the singer from that film, Wilhelmina Fernandez, in Boston, but it was before they made the movie. She was a singer, the real thing, so seeing her in the movie later on retroactively made my attending that performance at the Opera Company of Boston a magnificent experience, even though it was small in the grand scheme of things, as a Boston opera performance usually is.

I've always been into where the grandness of opera collides with the puny and the embarrassing. I still remember hearing Shirley Verrett sing Desdemona at the Boston opera. It was kind of a shabby set, and I saw Verrett's dress get caught on the floor, and she had to kind of tug on it! And I remember going to the Baltimore Opera two nights in a row, and on the second night, right in the middle of the curtain call of Il Trovatore, the curtain fell down. It just fell down. It was so grand!

AD: It's so physically extreme at times. There's a superhuman element to the very idea of operatic performance, and with anything on that realm, there's the possibility of disaster at any time.

WK: Yes, I think we all love the story about the opening performance at Lincoln Center, of Antony And Cleopatra with Leontyne Price, and the sets that wouldn't work, and the wigs that were too heavy.

AD: Have you seen the documentary yet? The Opera House, about that opening night?

WK: There's a documentary about that? What?

AD: Yes, a new one. I haven't seen it yet either, but they interview Leontyne Price at length in the film. She gets top billing, and she's the main talking head. She sings in it too, and the word on the street is that the voice is still there. She's in her nineties. She's my favorite American.

WK: She keeps such a low profile! I remember trying to get a press ticket to when she sang at Carnegie Hall, right after 9/11. I couldn't get in, and I was devastated, but I listened to it on the radio and I remember my astonishment. There were certain of her high notes that were still there and still resplendent. Are you tuned into Magda Olivero at all?

AD: Oh, god, yes. That's a really niche question. I've heard her Met Tosca , the late debut, when she was, what, 70? Unbelievable.

WK: I'm really tuned into her. She's a total Youtube discovery for me. In terms of a diva, and someone who did not lose her voice as she ascended in age, very inspiring.

AD: My current live and working diva whose voice I'm really excited to hear change over the next fifteen years is Nina Stemme, who was also the first great diva I ever got on a plane to hear, because she never ever sings in Los Angeles. I just went to see her Turandot in San Francisco. She's not slowing down at all, and her voice is as incredible as ever.

WK: I don't know if I've ever heard her in person.

AD: Oh, it's enormous. And a huge dramatic presence. She's someone who behaves according to whatever the contemporary Codes of Diva Conduct are. I waited at the stage door afterwards, and she agreed to take a picture with me, just as long as I promised not to put it on Facebook, which I thought was great. It reminded me of Wilhelmina Fernandez in Diva , not wanting her voice recorded.

WK: Does she have a Nilsson quality?

AD: Well, she's the great living Wagner soprano. And a friend of mine was teaching in Stockholm at her kids' school and apparently, she's personally very much the Birgit Nilsson type, the type who flies home after singing four Ring cycles and milks the cow.

WK: Tonight I'm going to the trough of Youtube to pig out on Nina Stemme.

AD: It's a wealth. I would be remiss if I didn't ask you to talk a little bit about AIDS and The Queen's Throat. One thing I didn't expect when I first read it was that AIDS is kind of a spectre in the book. It's around, but you do have to look closely for it, but it's kind of underneath everything. Presumably, you were writing this in the aftermath Golden Age of opera queendom... I don't really have a direct question for you, Wayne, but if you could speak a little bit to that moment and the creation of the book.

WK: This is underneath the whole book. Particularly in the last chapter, "A Pocket Guide to Queer Moments in Opera." I'm talking about Mimi's death [in La Boheme]: "The music at the end narrates and justifies our tears and hides that embarrassing release in a social context: Opera-going. Protocol determines that the performance will end, and that unable to find the exact words to describe this strange experience, we will dismiss it, underestimating melodrama's power to bind the solitary listener to a collective mourning."

I kind of felt there that I was saying something about the possibility of these extreme dramatic forms and the possibility, in a way, of solitary experience to intervene in this scene of death and disaster and suffering. I guess the paradox included that opera was a form beloved by the generation of queers who were decimated by AIDS. The opera recordings I had, many of them, were gifts or were from dead men.

The paradox of the passivity of opera-going, and its remoteness from contemporary culture and contemporary action, the pointlessness in a sense, and the way that opera is steeped in death, and death and love's ultimate embrace. La Traviata kind of says it all. Here was this art form that seemed to be talking about sex and death all the time. And here was this kind of cultural world of diva worshippers that was part of what AIDS was destroying. It was so overdetermined and complicated that I'm unable to describe the multiple exits and entrances that I found around this subject.

I remember speaking on NPR about the movie Philadelphia when it came out. Didn't it get an Oscar or something? There was some tie-in moment, and I was trotted out as this gay opera person to explain why this moment was so important, the scene with the aria "La mamma morta." It was widely felt in that era that between Angels In America, Philadelphia, and the community that I was describing in my book, that these issues were really alive.

Coincidentally, I didn't write the book in New York. I wrote it in New Haven. But I lived in New York in the 80's, and went to the opera a lot, and studied with opera queens, learned from them. I was like you then, a latecomer to this scene. My education in sex and death and opera were all simultaneous.

AD: In the years when you were becoming fully-fledged, what were some of your touchstones as you were learning? Is there anything you'd pass along to the newly-initiated?

WK: For the intervention, I would say the gold standard would be some of the footage of Callas in concert performances. There's a concert performance in Hamburg, and then the one in Paris. One or two of those are just unbeatable.

Some touchstones for me - and this wouldn't work for the intervention - were the live performances of Leonie Rysanek that I saw at the Met. It would be hard to figure out just from her recordings why she epitomized opera, but it was her dramatic conviction, the size of her voice, and this uncanny thing you can hear on her recordings, that the higher she went, the easier it became for her. And she would land at this point which was perfect for Strauss, where it hit the stratosphere. She would just kind of float up there, and she would just musically and physically exalt in her arrival up there, in this tonal zone most singers couldn't ascend to. It was thrilling.

I heard her sing Die Walkure in San Francisco, and it was the first time I heard a bit of The Ring, in 1981 or 82. She was in the same round of performances as Birgit Nilsson, but I went to the only performance that didn't have Birgit Nilsson as Brunhilde, but I did hear Rysanek as Sieglinde. My parents had bought me the tickets, so I was maybe in the fourth row or something, and I've never heard something so loud as her voice. She might have been sixty then, but it was so loud.

As part of the intervention, taking this person to hear Nina Stemme, this singer you love, and just saying to this person, "Okay, I'm going to give you some champagne, and we're just gonna go to this. You can sleep as often as you want during this, but you can't talk or look at your phone, and I'm just gonna elbow you for the moments you have to wake up for and pay attention to."

What would be yours? What would you put in the gift bag at the intervention?

AD: I guess I would start with Leontyne Price's blue arias disc. All the best arias, perfectly sung.

WK: Is that the really early one? What's that called? It's not The Art of the Prima Donna.

AD: That's Joan Sutherland, but I would include that as well. That's just astonishing, and so comprehensive. And I read recently that she recorded it in the matter of a few days.

WK: With Price, I have two of the early ones, the very early recordings. One of them is just songs.

AD: The Faure and Poulenc disc? It's great. But the blue album is sublime.

WK: I taught a course where I could have been your teacher. You would've been the ideal student in this class. Opera and Gender.

AD: Yes, I could've been your TA. And I have one final question before I go to therapy. I don't know if anyone's asked you to do a 25th anniversary edition of this, but if you had to write a forward or afterward, during the Trump era, when the culture is kind of on the Titanic, and every opera company is even more in jeopardy than usual, where would you begin? How would you present this book?

WK: To think of the disaster of the contemporary scene and imagine how I could bring my book into conversation is humbling and shaming at the same time. But, if I may, there are two things I don't address properly in the book.

Firstly, I overemphasize the listener's silence as a prerequisite. In the introduction, I would say: Let opera be participatory in some way. Find some ways to understand how un-passive your experience is. As an opera listener, you are someone who is helping to make opera possible. The listener is not a parasite. The listener is a co-player in the scene.

The important thing about loving opera applies to all unpopular objects of our affection. And so, the larger lesson of my book, and what I've learned from people who love my book who are not so into opera, but who understand that I'm talking about fandom in general, is how nourishing a passion for a forgotten or an undervalued object can be. And opera, though overvalued in some way, has always been a dying art. Whatever it is, I would just exort the reader to pay attention to the object that seems neglected, and understand that even with something like opera that seems so overbearing, it has neglected, unpopular aspects, and the people who hang out in the sphere of opera may see themselves as outcasts.

AD: In queer life right now, this kind of outcast fandom of something undervalued by the culture at large is very much alive, but now it centers around drag and RuPaul's Drag Race. I'm not a participant per se, but I think those two fandoms overlap emotionally and in practice, so it makes me wonder if some brainy young queer is one day going to write The Queen's Throat vis-a-vis RuPaul, for the age of Trump.

WK: Oh, please do. I would blurb that.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Wayne's most recent book of poetry is Camp Marmalade.