Illustration by Thomas Allen

When Richard House's multilayered, four-part novel The Kills was nominated for last year's Booker Prize, writer Philip Hensher singled it out as the contender that everyone ought to read, "a thrilling, overwhelming ride...full of lucid action, drifting contemplation, apparent dead-ends, confusion, and thuggish explosions." It is all those things, but the most interesting thing about House's success may also be the thing that matters least: his sexual orientation. House is gay, writing in a genre (the thriller) typically regarded as the preserve of straight male writers. Perversely, it's the inconsequentiality of his sexuality that makes what he's done so consequential.

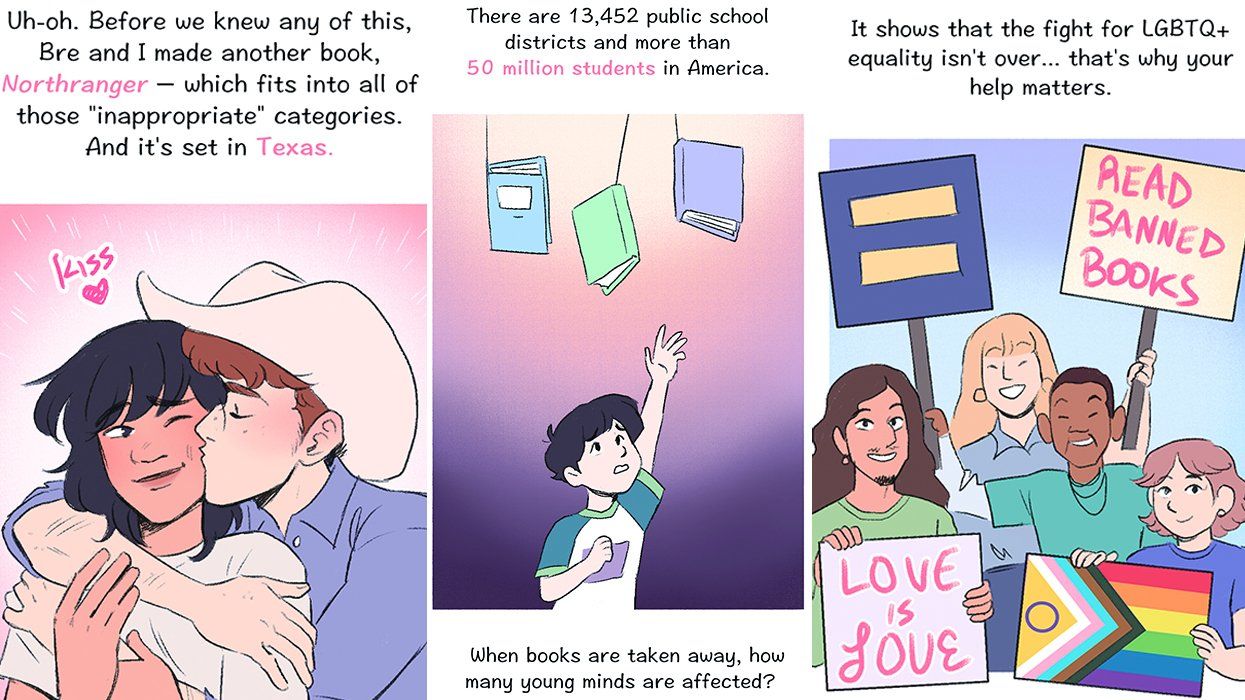

Only a decade a go, the best a gay reader could expect from a bookstore was a discreet "gay" section, ostracized from the general fiction shelves. Although non-gay readers might pick up James Baldwin's Giovanni's Room or maybe peruse the odd Edmund White title, the implication was clear: Gay writers and readers were not part of fiction's mainstream. Well-intentioned or otherwise, it had the effect of putting gay writers in a quandary. If they resisted identifying as gay novelists, they were seen as ashamed or self-interested, but if they embraced the label, they were admitting themselves to a ghetto. Today, literary novelists like Alan Hollinghurst, Michael Cunningham, and Sarah Waters routinely challenge the idea that being gay limits a book's success -- they are out, and so are many of their characters, but until now genre fiction has been slow to catch up.

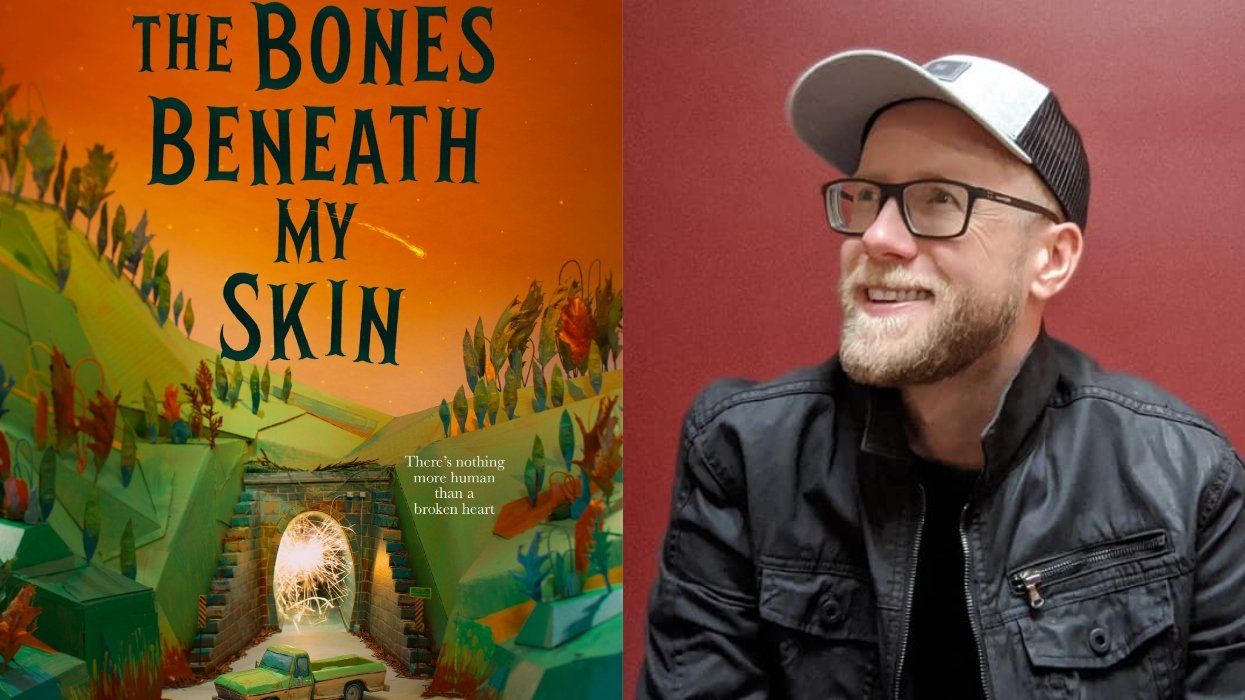

With its dense plotting across four interconnected novels, The Kills, published stateside by Picador on August 4, is not a typical thriller, but it has the pace and energy associated with the genre and it's already being compared to the work of John le Carre. Like fellow gay writer Tom Rob Smith, whose debut, Child 44, was an international bestseller (a film adaptation, starring Tom Hardy and Noomi Rapace, is coming to the big screen this fall), House has taken a familiar form and made it fresh, in large part by bringing his own perspective to the writing. The opening premise of The Kills -- a manhunt sparked by a deadly explosion in an Iraqi military camp -- sets the tone for an unnerving sequence of books within the book, in which various stories intersect and dissolve, characters lead us down blind alleys (or disappear), and motifs ping-pong eerily from one book to another.

Take, for example, the first book, Sutler, which features a gay American student traveling around Turkey wearing a T-shirt adorned with a star; a similar T-shirt materializes in the third book, The Kill, set in Naples among a cast of drifters and immigrants. This time it's a ghostly detail from a fleeting glimpse of a different American student (we assume) who may or may not have been the victim of a horrific murder that may or may not have happened. The book is full of such riddles (sometimes too much so).

Like Smith, House's work reflects a broader shift away from coming-out narratives that have long dominated -- and constrained -- our notion of what gay writers write about. Their characters are sometimes gay, sometimes straight, and approach life from the perspective of outsiders. There is none of the macho boys' club swagger that excites the best-seller lists. "It's a relatively recent position for a writer to be in," agrees House. "I think [my sexuality] is really present, but not in the most obvious way. What does it mean to be 'outside?' Because it's a position we all exploit in some way--we choose when and where and how to identify ourselves, and it becomes problematic when you're not able to control that."

House, already at work on a new cycle of novels that features two men who exploit a misconception that they're gay to take advantage of others, is great at conjuring place, and the locations of The Kills -- from Iraq and Turkey to Malta, Naples, Cyprus, and the Chicago suburbs -- are described in richly detailed, evocative prose that fully immerses the reader in the places he describes. It's something that Smith does exceptionally well, too. His new book, the tightly written, claustrophobic thriller The Farm, concerns the suspicious events surrounding a young woman's disappearance from a rural Swedish community, and is told from the perspective of a woman who may be having a psychotic episode. It is up to her gay (and semi-closeted) son, 29-year-old Daniel, to determine whether her story is true or false, a task made all the more complicated by the fact that it implicates his father in a crime. It's a book about secrets and trust, but also about how the people we think we know best may turn out to be the people we know the least.

The Farm is based on a real-life experience Smith had with his own mother, but he says any similarities end there. "It's interesting when people put it that Daniel is a version of me, because he really isn't," he says. "My teenage years were utterly miserable, and I wasn't remotely popular. I had to struggle through it in a way that was very different to Daniel, who hasn't really gone through the fire in the way that lots of gay people have."

For Smith, going through the fire meant suffering regular bullying at school, where he retreated into the world of books and studying. "The advantage of being unpopular at school was that I became intensely academic as a reaction against it and I read nonstop, and studied obsessively to fill the gap that was left by my vacant social life," he says. "I wouldn't change that for the world -- my entire writing career grew out of it."

You can see the influence of the great twisting French doorstoppers, such as Alexandre Dumas's The Count of Monte Cristo (which Smith read as a child), in his ambitious debut, Child 44, which concerns itself with the hunt for a child murderer in Russia in 1953 -- a time when fear was the principal tool of state control. Inspired by the true story of Andrei Chikatilo, who murdered more than 50 people in the '70s and '80s, Smith's best-selling book is a mesmerizing study of how the Soviet mentality enabled a serial killer to avoid capture for so long, in no small measure because of the way the authorities distinguish between homosexual, or "deviant," suspects and straight party loyalists (as Chikatilo was). "I remember thinking, Had they just followed the evidence and applied the same test to all the suspects, 30 to 40 people would be alive," says Smith. "It was an example of prejudice having real, concrete, and horrific consequences."

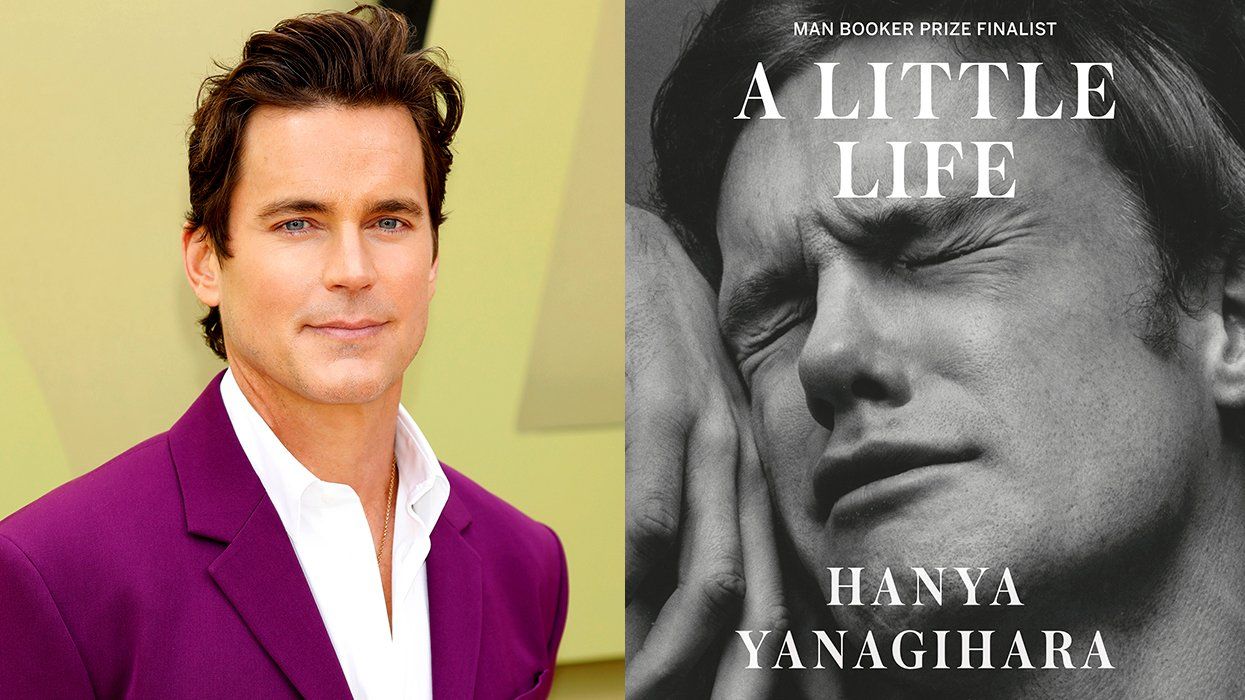

Smith is now in the midst of writing London Spy, a five-part miniseries for the BBC, coincidentally inspired after he was invited to adapt a le Carre novel that fell through for rights reasons. Unlike a le Carre novel, however, the central characters in London Spy are gay, brought into each other's orbit by the strange coincidence that Britain's intelligence headquarters stands opposite a well-known gay neighborhood in London -- Vauxhall -- crowded with bars and saunas.

"The John le Carre world of British spy thrillers is so codified; it's all about these subtle British mannerisms, a lot of which are very opaque and serious and have historically depended on coming from the right background and the right schools," says Smith. "I thought, Let's take someone from that world and throw them up against someone from the world that's directly opposite. Could this slightly hedonistic young man -- an idealist, a romantic -- could that person, who fell in love with someone who lied about their identity because they're a spy, take on the mantle of investigating his disappearance?" The project, produced by Working Title, best known for Four Weddings and a Funeral (as well as the groundbreaking gay indie My Beautiful Laundrette), is scheduled for 2015.

For Smith, the free hand he's been given reflects the changing climate for gay subjects. "No one, not the producers or the director or any of the executives, has said, 'Oh, we're worried about that' -- and there's some quite edgy material in it," he says. "There have been times when I've stopped myself and said, Oh, my God, I'm lucky to be writing at this point in the world, because 20 years ago, I don't know whether I would have faced more personal questions and more opposition, and whether just saying, 'It's going to be a sensational TV drama,' would have been enough. And now it feels like it is. It really does."

Read more about Richard House here.