Pitts and Von Stroheim, Gish and Sjostrom, Dietrich and Von Sternberg, Hepburn and Cukor, Crawford and Curtiz, Hara and Ozu, Grier and Hill, Rowlands and Cassavetes, Carstensen and Fassbinder, Huppert and Chabrol, Duvall and Altman, Seyrig and Akerman, Sukowa and von Trotta, Bonnaire and Varda, Cheung and Kwan, Paquin and Lonergan. I could go on and on. Like many gay men, I've always gravitated towards actress-centric films and stories about women, and the signature pleasure of my cinephilia has always been discovering an explosive collaboration between a shrewd director and a powerful actress who convey on a molecular level their mutual trust and understanding. It sometimes announces itself as a fierce and gendered battle for authorship of the audience's experience. Other times it bespeaks the timbre of mismatched instruments in perfect harmony. But you know it when you see it, and it's good any way you can get it.

Related | Hannah Gadsby's Nanette Is a Sea Change for LGBT Comedy

The latest enriching example is perhaps an unlikely one: Stand-up comic Bo Burnham's distinguished debut feature. Eighth Grade follows a kind and bright thirteen-year-old American girl named Kayla through her last week of middle school. Often lit by the glare of her ubiquitous smartphone screen, Kayla is a remarkable character. For all Kayla's better qualities, so pronounced is her social anxiety that her only portals to the world are her YouTube videos, in which she offers blissfully unfocused but sincere platitudes on being yourself and having confidence. She self-medicates with social media, and Burnham punctuates the narrative with the kaleidoscopic rhapsodies of light and color, filling the screen with Kayla's social media feeds and her active thumbs. We never find out what she's learning in school, what her grades are, whether she does her homework. Presumably her anxiety doesn't extend to her academics. But when Kayla arrives at a pool party, her anguished journey from the bathroom to the shallow end is as fraught with tension as the opening of Saving Private Ryan.

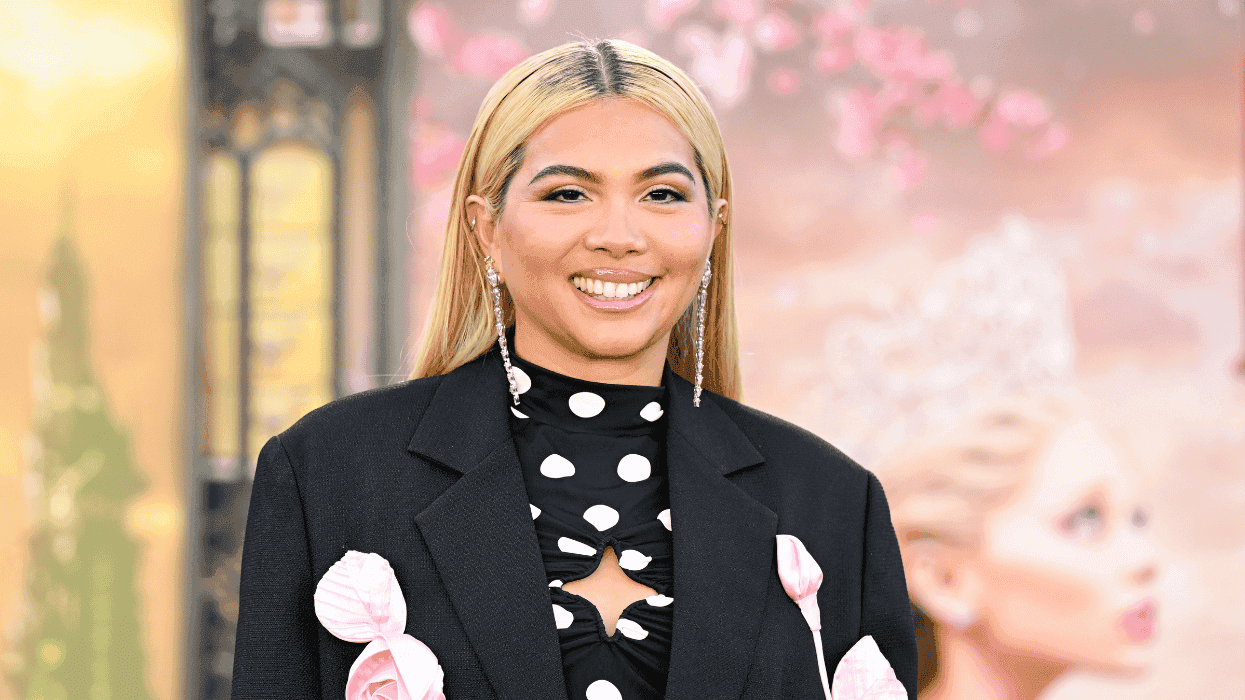

Tasked with carrying every single scene of this free-formed, essentially plotless narrative, a young actress named Elsie Fisher succeeds beautifully, and then some. A welcome antidote to her Disney-trained peers and a defiant middle finger to the scrubbed and sophisticated teens of mass culture, Fisher is a revelation, a true discovery. She projects nothing and delights in nuance. She has no discernible actorly vanity. Much of the film is in close-up, where we can watch her think and feel, and she has a direct and wholly natural shorthand with the camera. At Kayla's most vulnerable moments, Fisher's honesty is spellbinding. As the movie takes darker and darker turns, she and Burnham invest Kayla with such courage that I had to cover my eyes in shame. To top it off, she can land a joke.

This is not to say that the collaboration between Fisher and Burnham is the only pleasure to be found in Eighth Grade. The stage actor Josh Hamilton is sublime as Kayla's single father. His home-stretch good-dad monologue is a thing of beauty to rival even Michael Stuhlbarg's iconic speech from Call Me By Your Name. The splendid Emily Robinson, whom you'll recognize from Transparent, makes a strong impression as an older girl who takes Kayla under her wing.

As a comic, Burnham has always woven audience discomfort into his work, but in his first screenplay, he goes for the throat. Think about the last time you were around a maladjusted teenager. (That includes most of them.) Do you remember the unease you felt around them? Teenagers are unpredictable. Their identities have not yet taken shape, so they try various behaviors on for size to see how their world reacts. They remind us that we once did the same ignoble labor of learning to be. And to those of us for whom that age bracket is linked to trauma - I came out at fourteen at a single-sex Catholic school in a working-class Boston suburb - interaction with a flesh-and-blood adolescent can be torture.

Burnham knows this. He looks back the harrowing rituals of maturation with sympathy and humor, but he is ruthless in naming the unpleasant details. He prods at still-open wounds and compounds them with timely new terrors: Snapchat, school shooter drills, juvenile nude swapping. In our unavoidable recognition and identification with Kayla, we can purge old demons we were too ineloquent to name when they were conceived. In creating Kayla together, Burnham and Fisher are responsible for one of the all-time great screen adolescents. What a beautiful surprise: Eighth Grade, from a first-time filmmaker and a brand-new actress, is anything but juvenilia.