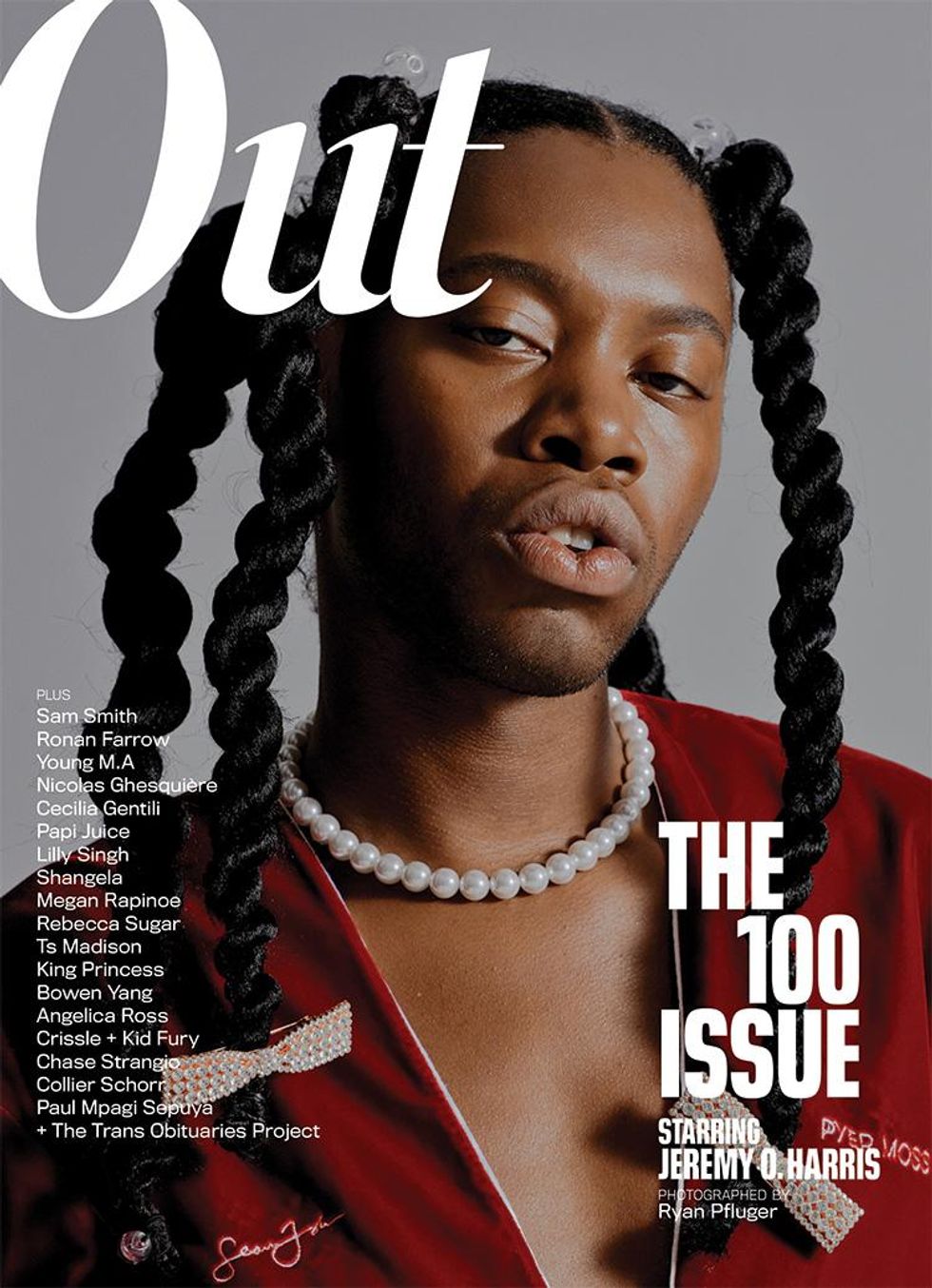

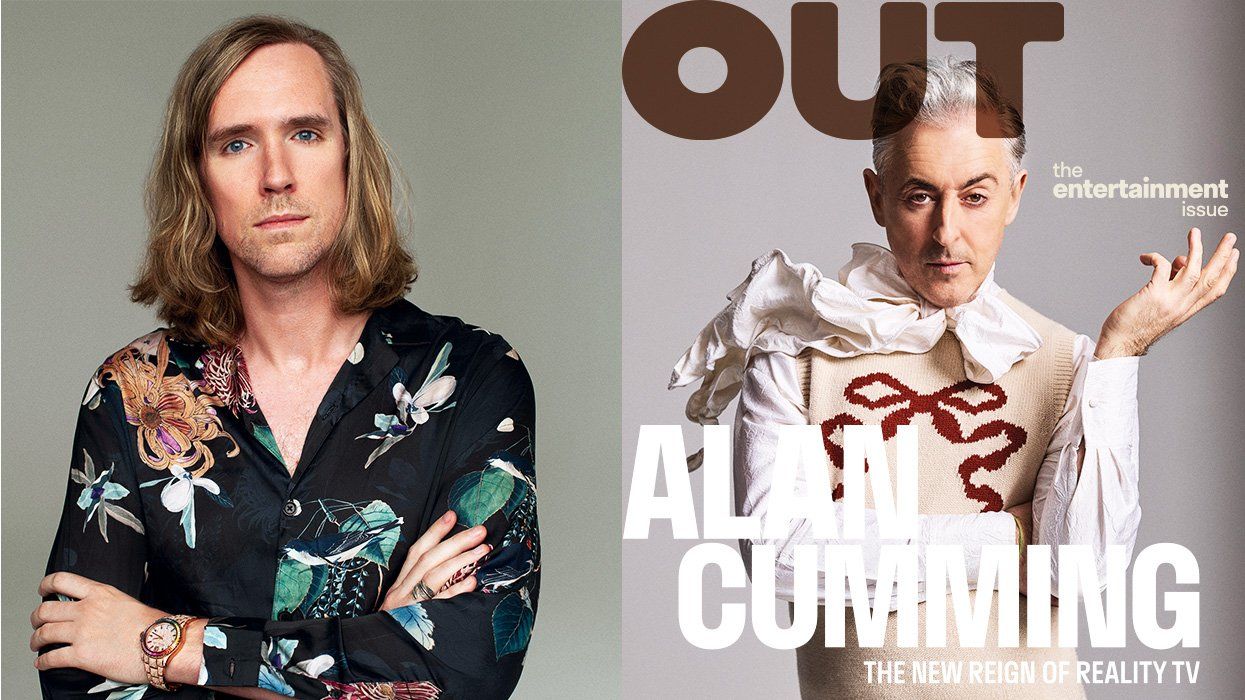

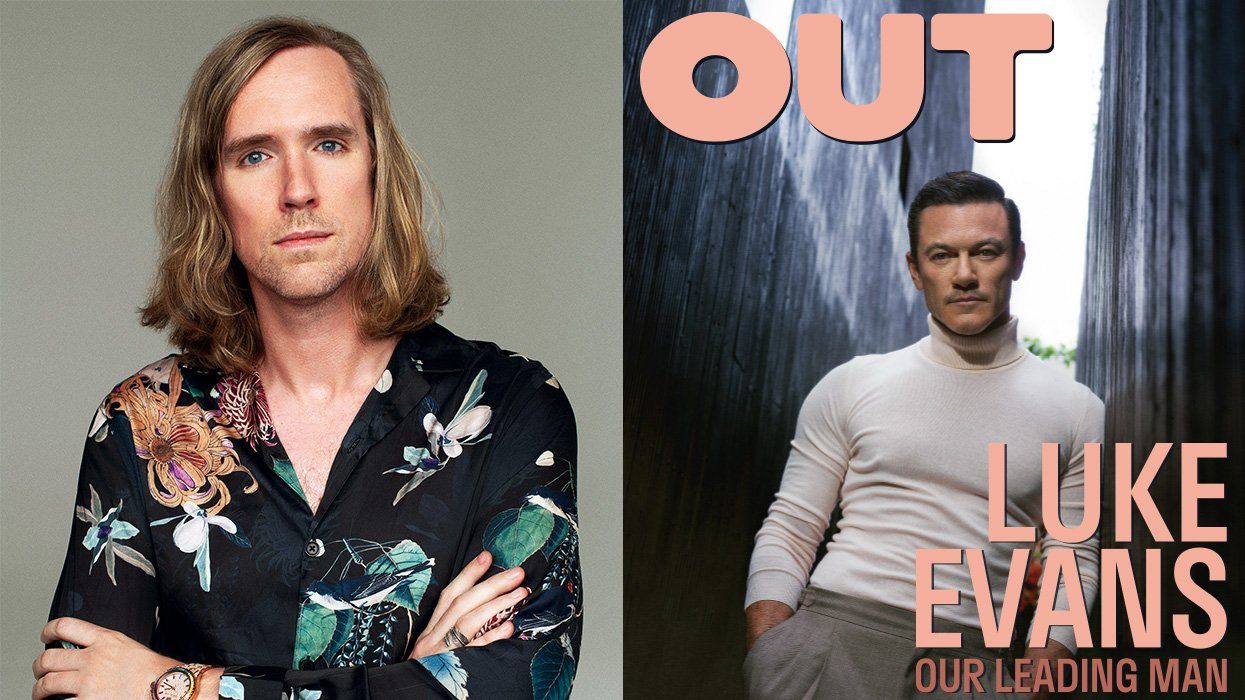

This year, Jeremy O. Harris became the youngest Black male playwright to debut a production on Broadway. To honor this milestone, he threw what's now known as the Blackest night on the Great White Way. Read about what else Harris is working on here.

Keke Palmer had to pee. It was act two of the critically lauded and much-discussed Broadway production Slave Play, a two-hour intermission-less performance, and the multi-hyphenate star had to go to the bathroom. So, she did.

Palmer stood up from her seat, crouched, raised a singular finger, and slowly started making her way down her row to the aisle. She quietly apologized along the way: "Sorry, sorry, sorry." But the audience of around 800 Black folks in the John Golden Theatre on Sept. 18 understood the gesture; they knew the "church finger," a hallmark of most Black Southern Baptist churches, now brought to Broadway. After all, they were there to witness Jeremy O. Harris' Blackout.

The inspiration for Blackout, a performance of Harris' Slave Play viewed almost exclusively by Black showgoers (legally they could not bar non-Black people, so there were a handful) came in part by frustration, and in part by a dare. The challenge -- or at least that's how the playwright took it -- was handed down by musician Kelela during a conversation between her and Harris for i-D. The star told Harris that she wanted to see the production, which deals with ramifications that race relations have on interracial relationships between Black and non-Black partners, with an all-Black audience.

On Top

Top and pants by Louis Vuitton. Sneakers by COMME des GARCONS Nike Air Max.

"She said it with such a ferocity and commitment that I had to meet her with the same ferocity and commitment. So I immediately said, 'It's going to happen,'" says Harris, who became the youngest Black male playwright to debut on Broadway when Slave Play opened in October. This accomplishment, however, wasn't initially the plan: Harris felt Slave Play was never meant to be shown on the "Great White Way." "I was like, 'I'd rather do this play at the Kings Theatre [in Brooklyn], because at least at the Kings Theatre we will have complete control. We can sell the seats for however much we want, and we can still get Rihanna there.'"

But weeks later, taking the work to Broadway became a reality -- and Rihanna, whose song "Work" plays throughout the production and whose lyrics are built into the set, still attended an early showing during previews, setting off a flood of criticism (and press) as she texted Harris from her seat, shirking long-held theatre customs.

But Harris' soon-to-be historic night was also borne out of frustration with a critique that accused the production of being made for the white gaze. During his time as a student at the Yale School of Drama, Harris had his stroke of genius that inspired Slave Play. "Someone at a party was telling a story about rough sex that felt out of step with his personal politics," Harris says of the work's origin story. "In that moment when I was challenging him about it, I came up with [Slave Play's two leading characters] and their dramatic struggle."

A mostly Black and brown audience on campus critiqued a 2017 production of the work as a broader part of Harris' deliberate exercise in creating theatre that finds new ways for Black bodies to take up space. It wasn't until the production started its first Off-Broadway run at the New York Theatre Workshop -- after he won the Lorraine Hansberry Playwriting Award and the Rosa Parks Playwriting Award -- that Harris was besieged with (mostly online) critiques that the show was made for a white audience, claiming the comical and sometimes cringe-inducing slavery-inspired sex scenes went too far and propped up Black trauma for the enjoyment of the white gaze.

So this night, which would be the first time a Broadway show hosted an all-Black audience, would serve both purposes: to specifically bring in Black people to view and experience the work in communion with one another, and to placate a challenge. An unexpected bonus was that inviting this crowd to Broadway for a special evening was also an invitation for his intended audience to take over and reimagine the theatre experience altogether.

On the morning of Blackout, as it's known, Harris says the production was still in need of $15,000 in funding. Money had been one of the main obstacles for putting on the evening (the team had the goal of making tickets available at $45 and $100, a more democratic price point than most Broadway productions).

"I didn't like the concept of, just because it's a Black night it should be free," says Troy Carter, one of the show's producers. Harris initially had thoughts of "reparations" by offering complimentary admission. "There's the idea that [Black] people wouldn't be able to pay for tickets, when that's not actually the case." And so, the team raised funds for weeks to set the tickets at what they felt was an ideal price. On the morning of, when they were still shy of their goal, Harris, Carter, and the entertainment company Level Forward each chipped in $5,000 out of their own pockets to settle the costs.

The 800 showgoers were selected mostly by hand. Harris and others from his camp personally sent out ticket links to possible guests with instructions to not publicize them; they composed a list of Black student organizations for press outreach; partnerships were made with the UK's Black Ticket Project, National Black Theatre, and ChiChi Anyanwu, a woman known for doing Black theatre nights for Off-Broadway productions. And it was that audience -- along with some star-studded names like Kelela, Palmer, Jesse Williams, Kelsey Lu, and Paloma Elsesser -- that commandeered the night.

Drippin' With Finesse

Top and shorts by Loewe. Necklace by BVLGARI.

"[People were like] what will other people of color feel?" Harris says. "And I had to say, 'I genuinely can't care.' The play literally has a line that says this therapy is for the Black people. So I have to walk and talk at the same time."

For the play's director, Robert O'Hara, it was clear from the night's onset that production had ceded control to the audience. Half of them were still standing outside the venue chatting at 8:10 p.m. for the 8 p.m. show, he says, which is particularly out of step for Broadway, where attendees are typically rushed to their seats (or could be refused entry altogether for being late). "It was like, 'Oh, we're going to take over this space,'" O'Hara says. "'We're going to decide when this is going to happen. We're going to decide when we're going to come into this venue, and we're going to decide when we're going to sit down.'"

When the crowd had finally settled, they were allowed to rearrange themselves, abandoning whatever seats they had been assigned. "I thought that sort of broke the boundaries and formalities of the codified space of theatre," Miles Greenburg, one attendee, says.

Before the show began, Harris also broke with Broadway tradition by emerging onstage to give a speech. (Playwrights are rarely seen on the stage -- and if so, they wait until the final bow.) Then, he invited writer and former National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellow Morgan Parker to read a poem she composed for the production, called "A Note on Your Discomfort." Finally, it felt like Slave Play was about to begin.

But then, it stopped. "It was like a rock concert," O'Hara says. "Rihanna's 'Work' started to play, and you would have thought the crowd expected Rihanna to come out! That happened several times that evening, where we had to wait for the applause or the laughs to die down."

In short, Broadway went to church.

There's an aspect of Black culture that emphasizes call and response. It's a part of our music, a part of our religious experience, and it's a part of our theatre. When you watch recordings of Tyler Perry's stage plays, for example, not only do the characters break the fourth wall to speak directly to the audience, but that audience speaks back. And that night on Broadway, maybe for the very first time, this audience felt like they were being spoken to. "When I saw this [with a typical Broadway audience], it felt as though I was kind of standing alongside the actors, informing a white audience of what our experience is," Greenberg says. "In an all-Black audience, it didn't serve that purpose. It got more personal. The things that hit me before hit a lot deeper because I wasn't perceiving it through any kind of filter -- it didn't feel like it was being addressed to anybody except me."

And so, the audience spoke back -- clapping, snapping, and verbally responding to what was happening on stage, evoking a feeling of community. This aired out the staunch, straight-backed feeling of traditional theatre, and made room for the audience to truly enjoy themselves. That meant they'd, like Palmer, sneak out to the bathroom when they needed to, then return later to finish their viewing. Ringers off, and with their lighting low, they texted on their cellphones, or whispered to their neighbors about the plot.

There were small moments when attendees would see themselves in the production and react accordingly, particularly at times the previous, predominantly white audiences hadn't. For example, there's a scene when Ato Blankson-Wood (who plays Gary, the Black partner of one of the play's gay couples) makes motions as if he's going to leave, revisits his decision, and turns back around to lay into his white-passing boyfriend. The crowd's reaction here also led to a pause in the show.

"This speech I have toward the end of the play deals with how, specifically, this Black queer body is valued and has valued itself," Blankson-Wood says. "It just felt like church. It felt like people saying amens, people saying yes, people snapping, people sighing, people in deep agreement...Those sounds of deep agreement, I will never forget it. There are layers to being witnessed. I felt like I was being witnessed as an actor -- this character was being witnessed and affirmed, which is an experience I have never had on a stage."

Photographed by Ryan Pfluger

Styled by Yashua Simmons

Hair by Hairbysusy

Makeup by Yuui Vision using M.A.C cosmetics

Photo Assistants: Nicol Biesek, Travis Chantar

Fashion assistant: Julian Mack

This piece was originally published in this year's Out100 issue, out on newstands 12/10. To get your own copy directly, support queer media and subscribe -- or download yours for Amazon, Kindle, or Nook beginning 11/21.