When Out asked if i'd be interested in writing a piece surrounding the Metropolitan Museum of Art's new Costume Institute exhibition "Camp: Notes on Fashion," opening May 9, and its curator Andrew Bolton, I was sitting at a bar in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, during the city's annual Carnaval festivities. I've since come to understand that Rio during Carnaval clocks in at a pretty high camp score: the feathery splendor, the street glitter, the costumed and sometimes satirical sex appeal. The hotel I was staying in -- the Copacabana Palace -- is very camp, both in name (it was never a palace) and in lore (it's shot in a 1933 film called Flying Down to Rio starring Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire). And, while there, I saw the supermodels Caroline Trentini and Jhona Burjack dressed head-to-toe in Jean Paul Gaultier, the former in a blush feathered bodysuit with extended nipples and second-skin over-the-knee boots, the latter in a bicep-baring pool-boy striped nautical getup. That may have been the most camp thing I've yet witnessed in about a decade's worth of fashion writing. In telling this to Bolton -- whose official title is the Wendy Yu Curator in Charge of the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wendy Yu tag because the museum now has endowed curatorships -- he laughed and spoke of a similar tale. "Gaultier is absolutely included in the show," he said. "In fact, we wanted this bright pink sailor suit he made to shoot for the catalog, and his archive manager said they'd love to lend it, but that it had gone to a friend who was going to wear it at Mardi Gras! We have it now, thankfully."

Bolton, who has been with the Met since 2002 (and has since put on a number of record-setting shows at the Costume Institute, including last year's "Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination," which was attended by over a million visitors), is both clearly excited about this year's programming and elegantly fluid in his explanation of its somewhat malleable translation. Though "camp" as a term came to the fore with a 1964 essay by Susan Sontag called "Notes on 'Camp,'" Bolton suggests that the word's definition has evolved with a snowballed gravitas since Sontag penned her analysis. There's one particular point of contention he holds with the piece, in which Sontag says camp is "style at the expense of content."

"Susan wrote her essay prior to Stonewall, prior to recent history. In reality, camp, while stylistic and aesthetic, has immense meaning. It has tragedy. Camp is artifice and kindness, it is a sensibility and a language, it is ironic and it is subjective. All of kitsch is camp, but not all of camp is kitsch. Susan gave us an aesthetical grammar to look back at history, but camp has developed since then. I think if she wrote it now, she would correct some of the things she said." He continues: "Camp primarily existed within the gay community. It was sort of this secret code of queer culture. And, as that culture has become more mainstreamed, so too has camp, hand-in-hand." Even though 2019 marks the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, Bolton says the exhibition's timing is a coincidence.

So if camp is indeed subjective -- Bolton also calls it "amoebic" and "hard to pin down" -- and now much more amplified, how exactly can it be defined in 2019? Take the Rio de Janeiro anecdote as an illustration: During Carnaval, the city was swathed in pomp and pageantry, leaving impressions ranging from good-hearted to scrappy to extra to humorous, all of which were tethered to and weighted by a more serious contextual purpose. (Carnaval is the period of merrymaking leading up to the start of Lent.) Partying as de facto national sport, escapist opulence, collective outrageousness: All are underpinned by a very human propensity for indulgence, even if and when staring down a long double-barrel of life's inevitable hardships. In Brazil's case, some of that hardship comes in the form of their newly elected president, Jair Bolsonaro, who has a history of homophobic rhetoric. Despite it all, camp often thrives during unrest and upheaval. (Bolton will mention this as well, as a general statement.) But how I see camp, how Bolton sees camp, and how anyone else sees camp can vary. The curator says, "It ranges from bad taste to incredible levels of sophistication." I think, after processing, that camp broadly means go-for-it exaggeration with a wholesome, light ethos.

Because of its relative amorphousness, Bolton used an academic approach in researching the concept: He traced its etymology. Camp first appeared in a 17th century play, as a French verb, camper, which concerned posing and theatrics. But camp's contemporary origin can be linked to letters that were written between two crossdressers named Fanny and Stella in mid-19th-century England. The pair would declare such activities as their "campish undertakings" (which a clerk would, rather inadvertently campily, actually, mistake for "crawfish undertakings"). Within the same era, Bolton found police records of a detained male sex worker who used the expression "camp" during his arraignment -- law enforcement officials had no idea what it meant. The sex worker said it stood for "amusement." Adds Bolton: "The word had no connotation outside of gay parlance in the 19th century."

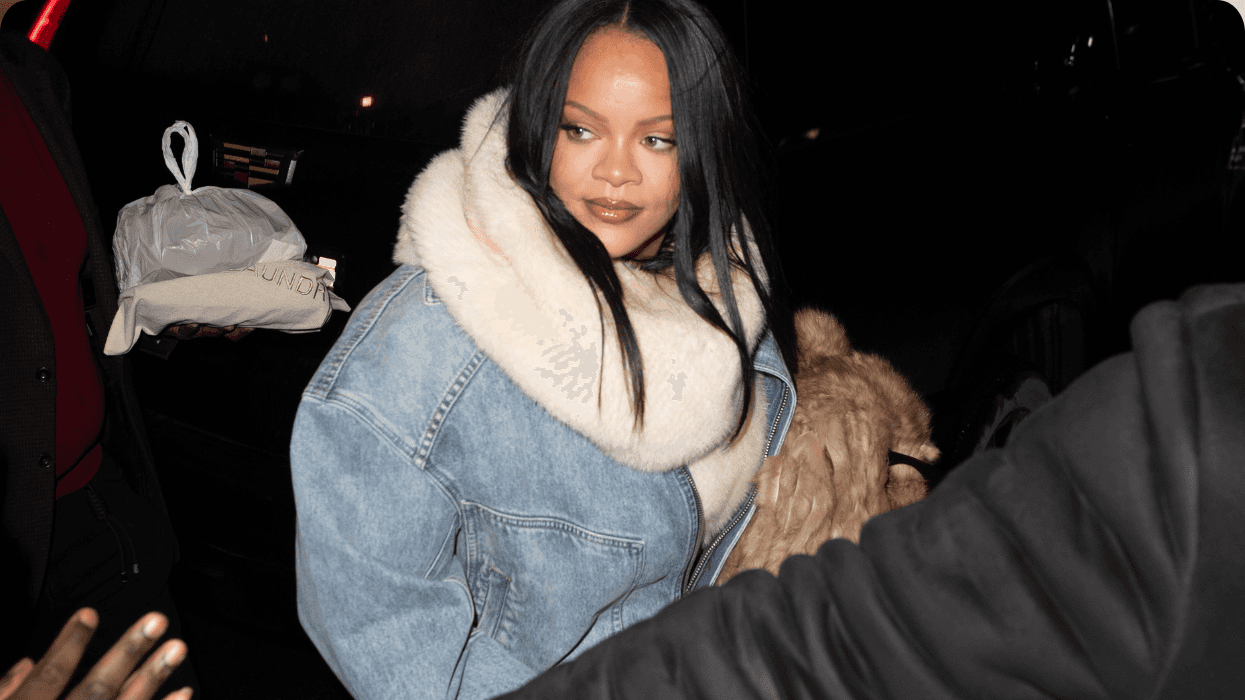

Bolton says that Sontag herself certainly "alludes" to homosexuality in her essay, now well into the 20th century, but that her explanation of camp is more aesthetic than social. In the time between 1964 and now, the etymology has morphed significantly. "When I was growing up, camp was still very much associated with effeminate behavior. Now, I wonder what a teenager or a person in their young twenties would say. I think that Kim Kardashian West is camp. J. Lo is camp. They're larger than life versions of themselves."

I ask if recent cultural phenomenons -- those driven almost entirely by digitization and social media -- can be viewed as camp. Consider: memes, like those seen on the Instagram account @best_of_grindr, the appropriation and adoption of verbiage used in drag or ballroom culture, and so on. Bolton thinks that the increasingly mass acceptance of gayness means that camp, too, has become more popular than ever, and that, while parts of it can indeed be gossipy or bitchy, it is never exclusively these things. "Some people disagree with me on that. I think there's an inherent benevolence in camp."

Which brings us to the fashion -- and what expectedly fabulous fashion there will be. Bolton cites the lineage of Franco Moschino and Jeremy Scott (who now runs the house of Moschino) as prime embodiments of camp. "Franco employed and Jeremy employs irony in such a generous way." He also names John Galliano, Thom Browne, the aforementioned Gaultier, and the late Karl Lagerfeld -- especially "all the trompe l'oeil, all the humor" from when he worked at Chloe. The show is broken into sections, including dandyism and "failed seriousness," which has to do with accidental camp, or examples of messaging that ended up not quite fulfilling their intended punch. Bolton says there is to be a fair amount of Cristobal Balenciaga and Yves Saint Laurent. Alessandro Michele of Gucci (who will co-chair the exhibition's star-studded opening party, the Met Gala) is also to be included, as is the Spanish designer Alejandro Gomez Palomo, who has garnered buzz for his gender-dismantling, boys-in-antique-dresses-centric collections. (Bolton says the breakdown between traditionally defined womenswear and menswear is approximately 60/40, respectively.)

And what about, say, Alexander McQueen, whose theatricality was as famous as anyone's? "There's no Lee McQueen in the show," says Bolton. "Camp has tragic characters, but it's not dark in the way that Lee was." There are also tabloid moments that non-fashion fans will likely recall: Remember 2001's "Swan" dress by Marjan Pejoski, which was worn by the Icelandic singer and actress Bjork to that year's Oscars? It was the subject of much public vitriol, but Bjork didn't care, and laughed all the way to those early-internet click-through hits -- utter camp!

"Camp is principally a language," concludes Bolton. "And it's an especially empowering language, at that." It may be too nebulous a conceit to ever wholly articulate, but given what's presented, and the deep study that went into it, it's evident that his and the Met's handle on camp is as fluent as a mother tongue.

This article appears in Out's May issue featuring artist Zanele Muholi and model Ruth Bell as cover stars. The issue is guest edited by Kimberly Drew. To read more, grab your own copy of the issue on Kindle, Nook, Zinio or (newly) Apple News+ today. Preview more of the issue here and click here to subscribe.

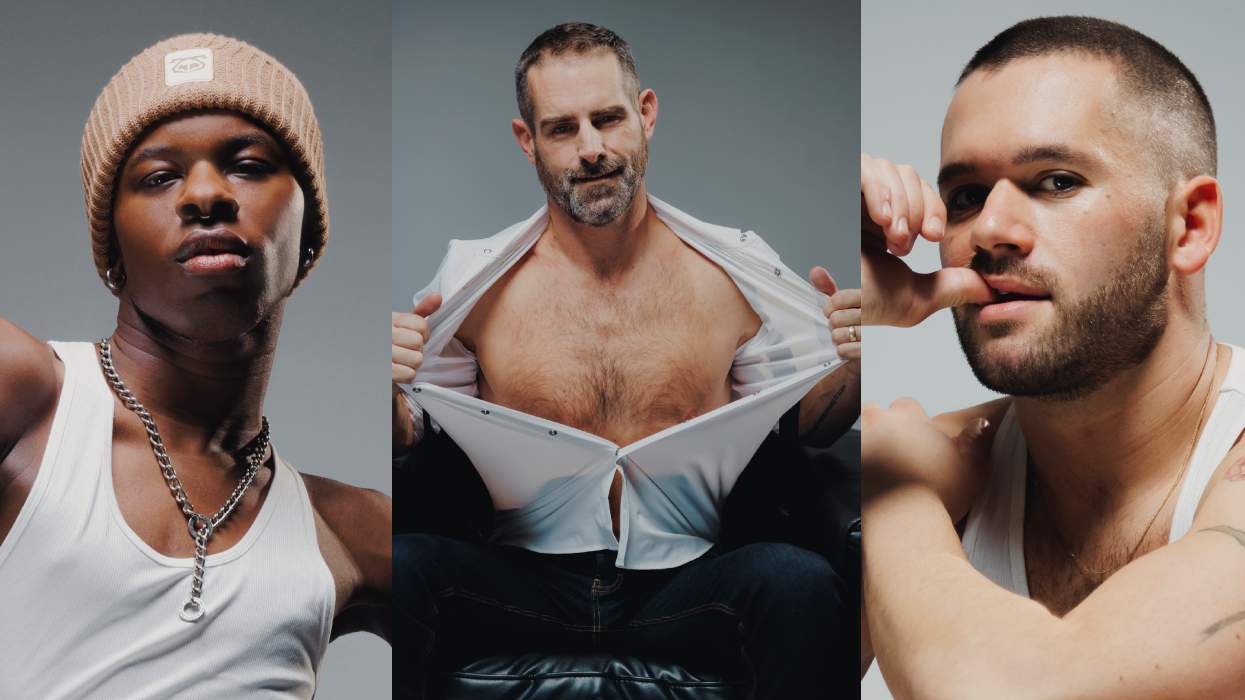

I watched the Kid Rock Turning Point USA halftime show so you don't have to

Opinion: "I have no problem with lip syncing, but you'd think the side that hates drag queens so much would have a little more shame about it," writes Ryan Adamczeski.