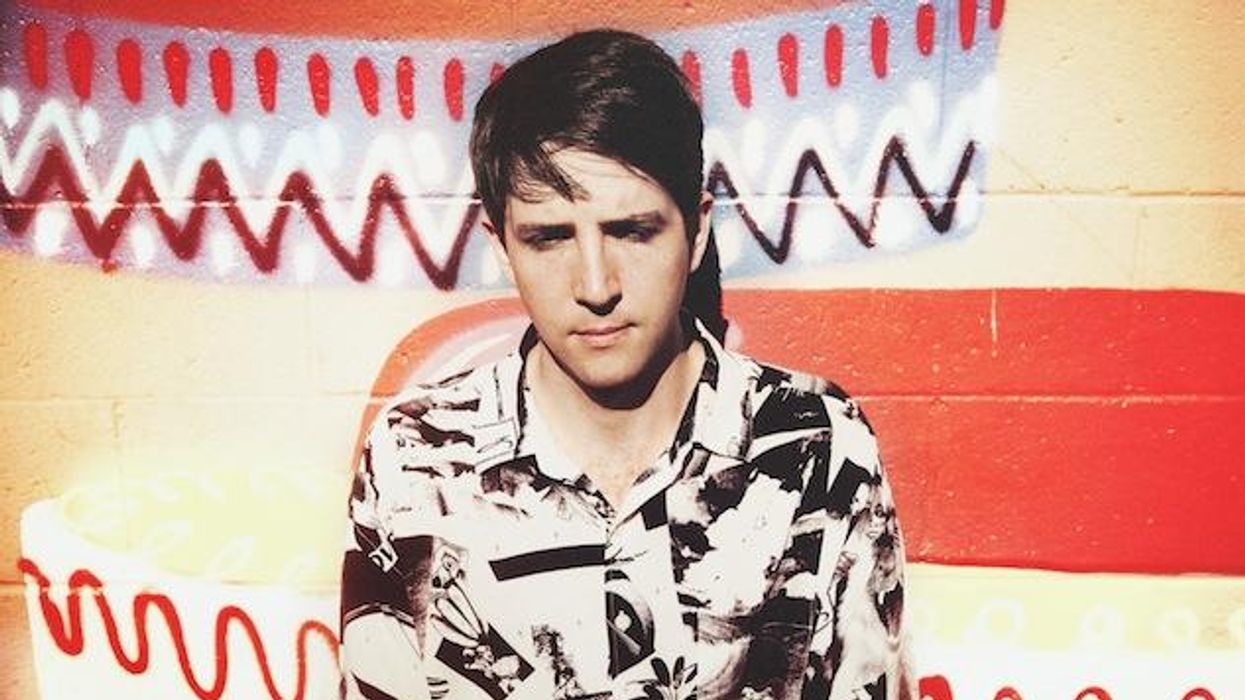

Photography by Peter Juhl

This past May an unassuming techie was setting up for Owen Pallett at the Bowery Ballroom, a music mecca in New York City. Pallett is a musician who, by virtue of his numerous talents, is a Hydra hyphenate: singer-violinist-composer-music theoretician-Oscar nominee-Katy Perry dissector. But then it turned out the techie a the music destination was Pallett himself.

After a bass-heavy set by his opening act, fellow Canadian outfit Doldrums, he moved unassumingly around the small stage, adjusting wires, lining up his loop pedals, setting up his keyboard, and placing his violin lovingly atop it--although Pallett is years away from playing for peanuts in college basements. The crowd waited under the half-light of a pre-show house, holding back a cheer, perhaps in awe of the modest nature of such an entrance. It was only once Pallett had removed his sweater to reveal a brightly colored T-shirt that anyone in the audience let out a woot of recognition. Given the rapturous reactions once the performance was underway, it's a miracle that such a muted greeting occurred in the first place.

The crowd itself, though composed of diverse types, was predominantly of one type: stylish, handsome, respectful, and earnest-looking gay men. I can't recall having seen such an enamored group of queer guys since the early-aught days of Rufus Wainwright's prime. Indeed, Wainwright--half-Canadian, also gay, also a progenitor of musically-complex and, when necessary, louche pop-rock--seems to be one of the most logical musicians to invoke when discussing Pallett. Whereas Wainwright has always cultivated a wry, if wise, tone in both his work and his public persona, Pallett is something else--an honest and unblinking workhorse whose compositions are informed by equal parts arithmetic and divination. His new album, In Conflict, is a glittering behemoth.

Pallet is known in music circles as a fabricator of multi-layered, cerebral alt-pop, a symphony of intricately-assembled strings, serve-and-volley percussion, and sweeping leitmotifs that suggest a galaxy of sound instead of mere songs. (Under the name Final Fantasy, he won the 2006 Polaris Music Prize for an album called He Poos Clouds, and that was his score, in collaboration with Arcade Fire's William Butler, that you were hearing in Spike Jonze's Her.) Atop all of this is Pallett's pure--and often underpraised--voice. More than one critic has used the term "choirboy" to describe its timbre, but such a term does it a great disservice; instead of the naivete and innocence that such a term implies, his voice is capable of incredible expression and has an evenness of tone that few other singers in any musical genre possess. (If you asked me to define Pallett's actual vocal range, I'd fail. It seems to have no beginning or end.) Pallett knows this, and he often builds walls of sound that reach their climax just as his tenor soars to its greatest height. His biggest "single," "Lewis Takes Off His Shirt," from the stunning 2010 album Heartland, demonstrates this rather ostentatiously, with Pallett ascending the scale as if in some startling vocal exercise.

But if it were just a beauty of sound for which Pallett were aiming, he would be of a piece with many other performers in the current landscape. He is not. He is a rarity, a necessary and inviting aberration, and a savant when it comes to human emotion. Immediately adult and sage where his earlier albums were fanciful, In Conflict is a cohesive yet expansive work that rings true in a queer world much more open than the one in which Wainwright once found himself. The first song on the album, "I Am Not Afraid," signals a conscious acknowledgement of this changed world from the very start: " 'I am not afraid,' ze said, 'of the non-believer within me," it begins, committing firmly to use of the gender-neutral pronoun. The word is used matter-of-factly, without pretense even though looped violins herald its arrival.

Over the course of the album, moments of sexual frustration and delirium appear with similar candor. "The Passions," in which Pallett teases out his voice to haunting effect, finds the singer in a compromising position ("You hooked your pinkies on my jeans / I'm 28, and you're 19"). On the title song, an awkward come-on falls into the music with a wink and a sheepish smile:

"I have no statement for your benefit, young man

Except this: we all will live again in the eyes of an actor

And the light on the glass

So let me see that ass. Hey hey hey!"

In the past, some critics have called out Pallett's turns of phrase and allegories as self-indulgent or merely precious, but I see something else at work: they're simply a poetry necessary for the poetic music on which they're being grafted.

In recent dissections of pop music on his own blog and then republished by Slate, Pallett has highlighted the calculated brilliance of singles such as Katy Perry's "Teenage Dream," Daft Punk and Pharrell's "Get Lucky," and Lady Gaga's "Bad Romance." A similar alchemy of ear-catching music informs his own work. "Song for Five & Six" (the fourth track on the new album, his fourth) emerges as a prime example of this. The climax of the song, which includes the conflagration of strings, percussion, and rushing bleeps readily associated with Pallett's work, is so gorgeous that it seems psychosomatically configured to please the ears. But through it all is a credible current of anxiety tempered with self-actualization. It's a classic Pallett moment, and I'd be hard-pressed to name many other musicians working today who are, at once, capable of such a complex hodge-podge of musical motifs and genuine emotion.

Moments like this on the record call to mind Wainwright creations such as "I Don't Know What It Is" or "Beautiful Child" from 2003's Want One - songs that present similar assortments of looped vocals and opera-large flights of fancy. Like Wainwright, Pallett is fully-formed as a composer, as someone who has thought through his work thoroughly and delivers an exact facsimile of the extraordinary fantasies going on in his mind. (One of the new tracks is, in fact, titled "Infernal Fantasy. As with other songs on In Conflict, Brian Eno has a hand in its creation.)

Pallett's work owes not a little to another musician whom he has recently invoked in online encomium--Tori Amos. Like Amos, Pallett is a multidisciplinary artist whose key talents are often overlooked in sight of a tidier narrative. Critics have a tendency to focus on Amos's prolific body of work and unique personality instead of on the particulars of her composition and, above all, the purity and breadth of her singing voice. At the Bowery Ballroom show, Pallett was exhorted to cover an Amos song during his encore, and he conjured up a section of "Pretty Good Year" to eager enthusiasm from the crowd. It seemed a perfect pairing of a past generation and the present one. Like Amos, Pallett is a kind of shooting star: He is a peerless vocalist and a fine songwriter and an inspired composer and a singularly gifted violinist and a deft lyricist and a fully-formed ethnographer of sounds and the body electric. (That he should also be tall, lithe, and handsome seems almost cruel.) Buy In Conflict immediately and behold its confidence. It's a presage of a more compassionate era in music and a great breakthrough for an already great artist.

Rakesh Satyal is the Lambda Award-winning author of the novel Blue Boy.

Watch the video for "Song for 5 & 6" below: