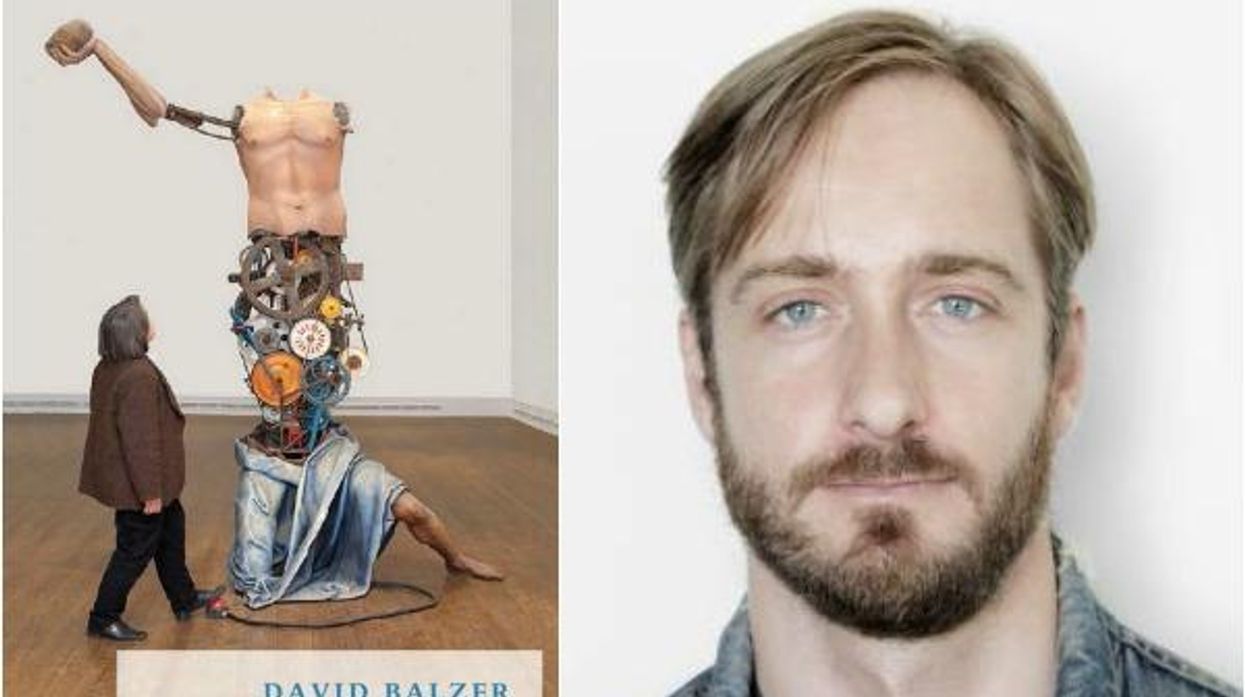

This is an excerpt from David Balzer's book, Curationism: How Curating Took Over the Art World and Everything Else. Balzer will be in New York March 6 to lead a panel discussion on his work. He will be joined by Ben Davis, Orit Gat, David Everitt Howe and Zoe Salditch; the talk is co-hosted by CART, and is being held in Cabinet's event space. More details are here.

You got dressed today, perhaps laying out various options in the manner of an installing curator. Perhaps, for lunch, you went to Chipotle, Subway, Teriyaki Experience, or one of any number of food chains that now ask you to select ingredients to compose your meal. (Subway got in early on curationism, calling their sandwich-makers "sandwich artists" in an amusing, telling marketing of the artist-curator relationship as parallel to that of the server-customer.) Perhaps you purchased something from an online retailer like Amazon or Everlane, consumer-curatorial work that will result in subsequent emails from the retailer suggesting other products you might like. Perhaps you updated your profile on a dating website or app, further streamlining your identity to attract the right people and repel the wrong ones, curatorial work that will also result in further suggestions of who you might like. Perhaps you spent some time on Facebook, organizing a photo album of your latest trip, or updating your cover photo to something cute and clever, an addition to your own digital exhibition of personal and cultural imagery.

Perhaps, on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Google Chat, Google+, or a sex app like Grindr, Scruff, or Tinder, you curated connections, making new ones, perhaps hunting by geographical location, and/or favouriting/deleting/blocking existing ones. Perhaps, finally, you unwound with Netflix, Hulu, Mubi, or another film- and z-watching service incorporating your every selection into further selections tailor-made for your tastes.

Some of you actually got paid to curate. If you work in fashion, you are probably curating in some way every day. As a model scout, you are looking for the next face, perhaps not even fully formed, but, as your eye and industry knowledge can tell you, eminently groomable. As a retail worker, you might arrange displays in addition to organizing racks and suggesting what works best for each client. If you work in a large department store, this job will go to a visual merchandiser -- not just a window dresser any more, for a visual merchandiser can function in all sorts of environments and, actually, very conceptually, and outside the fashion world. In fashion and other lifestyle industries, such as food, the role of the stylist has emerged as a prominent curationist profession. (A friend of mine in fashion recently told me, "We didn't know we needed stylists until you could tell who didn'thave one," a smart comment on how curators spin wants into needs, becoming their own best value-imparters in order to seem indispensable.)

Stylists, working in an editorial capacity, are, in true curatorial mode, collaborators, liaising with photographers, editors, designers and -- especially if a celebrity is involved -- the model or models, to determine which looks work best and are most strategic for the season. (Another friend of mine who has done styling cleverly referred to these acts as ones of "negotiation.") And this is just scraping the surface. In any lifestyle industry closely connected with media, you will find entire subsets of workers who are paid to activate their own cognition to select. Likely they are bringing their curated crops up through a hierarchy for ultimate approval, as evinced in the 2009 documentary The September Issue, in which Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour is basically pictured in every scene pointing at things and saying "yes" or "no." If you work in digital, you are also getting paid to curate.

Speaking of crops, perhaps the most common curator of our time is what has become known as the "content farmer." (Compare and contrast, figuratively, with writer Douglas Coupland's well-known coinages of the postmodern economy from Generation X, in which he referred to the office cubicle as the "veal-fattening pen.") The content farmer is the dystopian new journalist, producing online content, typically for a large company, based on search data from engines like Google, in an attempt to garner more advertising revenue because of the popularity of the topic. Here, the value impartation is done by others (droves, really) via algorithms. Value is thus proportional to popularity, and audience courting is synonymous with it. There is no better example of the darkest, most tautological aspects of accelerated curationism: Rather than the simulated democracy (or, at least, simulated beneficence) of curated works being presented as attractive to a potential audience because they have been chosen exclusively and carefully for their value, the value in these content-farmed works lies not in preciousness but in popularity. It is not a stretch to connect content farming to the increasing art-institutional interest in touring exhibitions. Revenue is scarce, so give the people what they want.

You may do something else in the fields of the cognitive or information economy, producing tweets for a large company, for example, typically for little or no pay. As with the curatorial profession in the art world, digital-curatorial jobs tend to divide feudally, except the elite class in the digital realm is considerably larger and more entrepreneurial. These are often new types of designers. If you are a game designer, you are intimately involved in the curatorial act of audience courting, but you are also - as we saw with banks and other corporations - recruiting gamers as curators, asking them to manage their own experience, interactivity being an increasingly fundamental aspect of gaming. (Such recruitment is also instrumental to app design.)

Experience designers are also a new and growing breed sprung from the curationist moment. Writing for the Australian website the Conversation, author, educator, and qualitative researcher Faye Miller begins by pegging the following fill-in-the-blank phrase as "the unofficial catch cry" of the 21st century: "It's not just a _____, it's an experience." Miller cites the concept of the "experience economy" or "exponomy," which she traces back to a 1998 article by B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore in The Harvard Business Review, essentially contending that commodities have more impact when the consumer has an experience, one that is often collaborative and cross-platform. Miller uses the example of "a major fashion event [that] would collaborate with the entertainment, media and tourism/hospitality industries to provide an audience with a lasting impression through a multi-sensory experience that is both enjoyable and prosperous."

To me, someone who deals with culture and its discourses rather than business, the description is redolent of biennials or large-scale conceptual-art projects in which curators are frequently instrumental. Miller, naturally, positions the late Steve Jobs as an incipient experience designer, quoting one of his many curationist quips: "Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn't really do it, they just saw something."

Excerpted from Curationism: How Curating Took Over the Art World and Everything Else, copyright (c) 2014 by David Balzer. Published by Coach House Books. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.