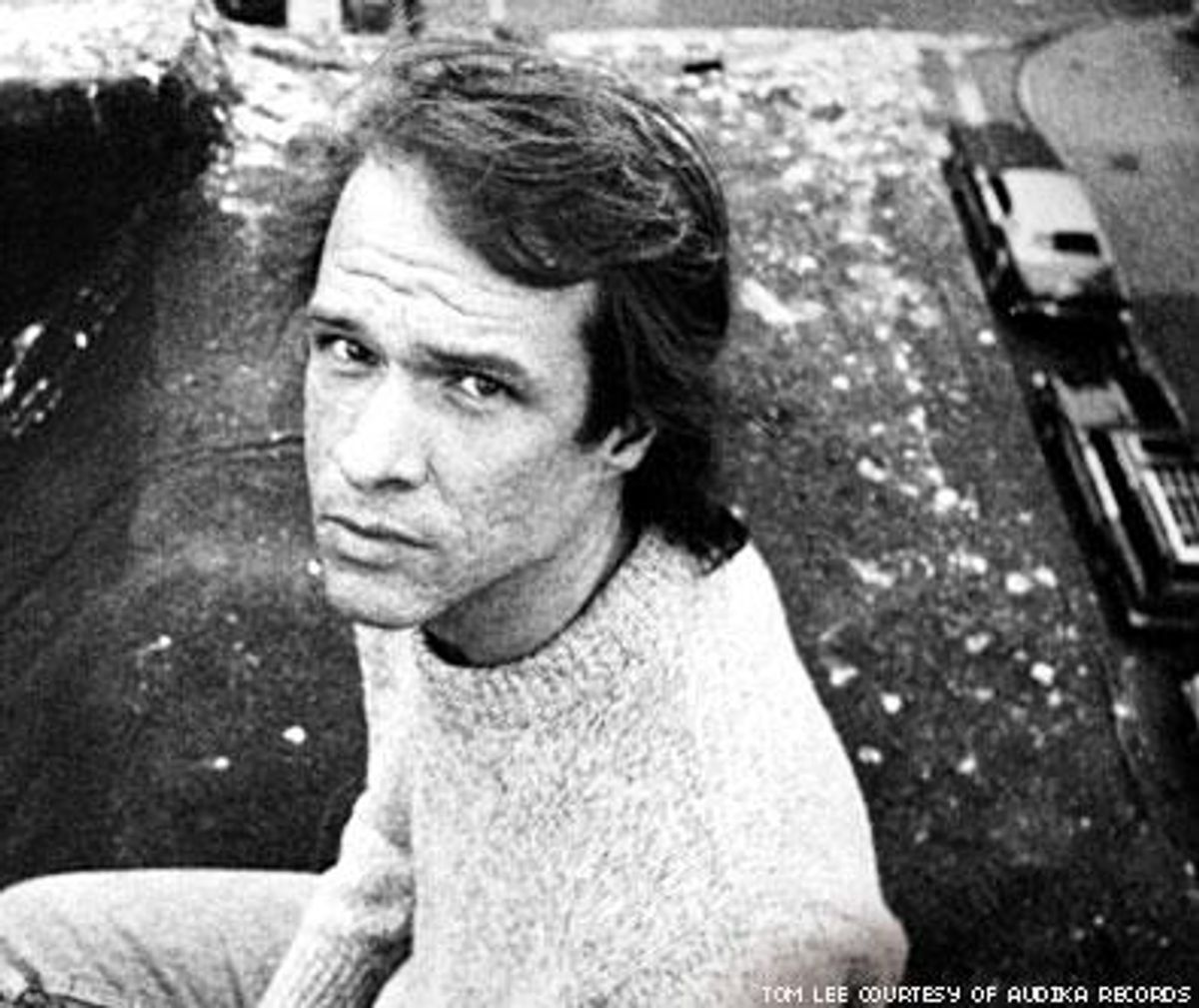

Arthur Russell is the best musician youve probably never heard of, and unlike others about whom you could say that, he courted anonymity, recording tapes at home and under silly aliases like Dinosaur L and Loose Joints. In most of his photographs hes wearing headphones as if they were a magic invisibility helmet, turning his painfully pockmarked face from the camera, hiding behind a perpetual blink, or staring, sad-eyed, at some point beyond the lens, as if willing himself to fade from the frame.

He didnt get his wish. Although Russells life ended early -- he died of AIDS complications in 1992 at age 40 -- today, he looms large over modern music. By his passing, Russell left behind 900 tapes containing approximately 400 songs, ranging from irresistible disco to heartfelt folk to the sparest of instrumental abstractions. This material, which has been released in a steady trickle since the mid 90s, makes a compelling case for Russell as one of the most important artists of the last half century -- and a primary influence on a generation of indie musicians devoted to cut-and-paste and composing home-studio intimacy, the Apple GarageBand generation. He is owed a heavy debt by very

now dance bands like Hercules and Love Affair and the electronic production factory of the moment, DFA, whose Tim Goldsworthy oversaw a 2006 remix album of Russells work,

Springfield. There is a direct line from Russell to indie-chamber acts like Final Fantasy and Grizzly Bear -- gay and straight and in between.

If the Arthur Russell renaissance has been growing for years, its now coming into full bloom. A new album of Russells pop songs,

Love Is Overtaking Me, will be released by Audika Records, on October 28. Folky and song-driven, it is one of the strongest releases in his catalog. Also this fall, the documentary

Wild Combination lifts the veil from his life and work, featuring interviews with his partner, parents, collaborators, and hipsters favorite Swede, musician Jens Lekman.

Arthur is one of those figures I grew up hearing about but never knowing much about -- a ghost, a casualty, says Nico Muhly, the 27-year-old nu-classical composer who has worked with Bjrk and Philip Glass. He represented the unattainable community that was New York in the 1970s and 1980s. In his instrumental music you can hear the ecstasies of Terry Riley, the insouciance of Zappa. What Ive always liked most about his music is the way in which it casually insists on the breadth of its influences: Disco happily coexists with abstract instrumental music without making an effort. His songs represent his community: concrete, abstract, gay, hedonistic,

forward-looking, and dancing.

Russell was a classically trained cellist, but he made music for dance floors and darkened living rooms, not elevators. His dance tracks are the most accessible and playful. Is It All Over My Face? from 1980 pits a laconic -- and possibly stoned -- soul diva against a double-edged lyric that references either a love-struck smile or the aftermath of a blow job. Remixed by Larry Levan of Paradise Garage fame, it presaged the entire garage house subgenre. Get Around to It is a cello-and-synthdriven rhythmic swirl that was recently covered by Tracey Thorn of Everything but the Girl. Wild Combination is a burbling Talking Headslike dance jam about a couple in the flush of love: I just want to be wherever you are / Hard as I can be, its never too hard. All of them rank among the best dance singles of the era. None of them hit the charts.

It was in disco that Arthur developed a queer musical form that was groundbreaking, says Tim Lawrence, a straight British academic and the author of a forthcoming Russell biography. Other artists, like Carl Bean and Sylvester, had explored the crossover potential of gay identity and disco, but Arthur went quite a bit further in Is It All Over My Face?, Pop Your Funk, and Go Bang. They alluded to more identity and desire and became important markers for downtown New Yorks gay population.

His pureness of heart is a rare thing in music, says Grizzly Bear bassist Chris Taylor. Its so relevant. So much of his stuff sounds like it would be the hottest thing ever if it were coming out today.

I liked how ahead of its time he was and how many types of music he made, says the Hidden Cameras Joel Gibb, who covered Wild Combination. He was doing stuff that wasnt necessarily expected from gay music. He broadened the definition and the expectations.

Arthur Russell was born in the corn belt town of Oskaloosa, Iowa, in 1952, and was an iconoclast from the beginning. He spent his teenage years with his cello and a severe acne problem, then discovered Buddhism and marijuana, fell out with his conservative parents, and ran away to San Francisco after high school to live on a Buddhist commune and study Indian music. The sexual freedom and mind-expanding possibilities of the nations gay capital in the psychedelic era laid the foundation for the rest of his life and work. I think you can hear the Buddhism in his music, says Taylor, the openness and linear quality of it. Along the way Russell met the poet Allen Ginsberg. They were neighbors in New York City, where Russell moved in 1973, and Russell gigged around with him, playing the cello while Ginsberg read his poetry.

Russells musical rsum grew over the next several years. He played in a couple of pop-oriented bands, the Necessaries and the Sailboats, which added guitars and drums to Russells voice and cello; they toured but never really got off the ground. He spent a year as music director of the Kitchen, the downtown performance space. He performed as part of the collective Flying Hearts with Modern Lovers bassist Ernie Brooks and others, including occasional guest David Byrne; he also played cello on an alternate version of the Talking Heads Psycho Killer and collaborated with Philip Glass.

Through it all, Russell continued making recordings in his apartment and releasing them piece by piece; his 1979 dance single Kiss Me Again was the first dance single released by Sire Records (later home to Madonna); subsequent tracks Go Bang, Wax the Van, and Tell You Today appeared in the early- to mid-80s on tiny indie labels like Russells own Sleeping Bag Records. Although he swooned to ABBA as readily as Mozart, he was resolutely independent; equal parts purist and perpetually insecure adolescent, he was allergic to self-promotion, and he refused to cede creative control to the degree necessary to land a major record deal. So he released his records himself.

He probably released more records than any of his downtown peers, at least running up to the mid 1980s, at which point he seemed to struggle to get his

music released, says Lawrence. For a while people would look at Arthur and think,

Shit, this guy isnt just making great music; hes also getting it released. Arthur also came very close to getting a major-label deal for an album, and one of the reasons he failed was that he was so committed to making music across a broad range of sounds. John Hammond of CBS approached him. He wanted Arthur to be the next Bob Dylan or Bruce Springsteen, but Arthur never just wanted to be a singer-songwriter or the leader of a rock band, and that frustrated Hammond, just as it frustrated a series of other record company executives.

People talk about his connection to the avant-garde or whatever, says Gibb, but he was a really good songwriter -- he had the folksinger-songwriter sensibility.

If Russells disco recordings were complicated alchemy, his bedroom tapes are magic in their raw emotion. You can make me feel bad if you want to, goes the refrain to You Can Make Me Feel Bad, Russells cello groaning under a fuzzy NirvanaGuided by Voices guitar line. Im so busy, so busy / Thinking about kissing you / Now I want to do that without entertaining another thought, goes A Little Lost, a shimmering teardrop of a dance ballad.

In Im Losing My Taste for the Night Life you can hear the tripartite tensions of being gay in the 70s -- the temptation to sleep around, the desire to settle down, and the guilt that affected both of these options; it is almost unspeakably profound. Or maybe its about a truck driver and concerns none of those things. Im looking for something I dont want to do / Because my coming to town took me from you.

Arthur Russell recorded most of his compositions in a sixth-floor walk-up apartment on 12th Street in New York Citys East Village. His former partner, Tom Lee, has lived there since 1980. The look is ramshackle bohemia preserved in amber: caramel stucco walls, beige tweed couch, thin printed rugs hiding uneven floors, kitchen cabinets covered with scrim. Theres a bathtub in the kitchen and a loft bed. Richard Hell, the poet and founding member of Television, lives one floor below; Ginsbergs old apartment, which is still held by his estate, is a floor below that.

Arthur was a hard guy to explain to parents, says Lee, chuckling. I would bring him home, and he would just sort of sit there with his headphones on.

Back then, Lee was a beautiful boy with bright teeth and a swoop of dark hair. He has matured into a handsome gent who teaches first grade in the New York City public school system and has the soft voice and encouraging manner befitting his vocation. He was and is Arthurs biggest fan. They met in 1978; Russell was Lees first boyfriend, when Lee was 29, and the love of his life. One of their first dates was to see Talking Heads and the B-52s in Central Park.

In most photos in which they appear together, Lee is beaming radiantly at Russell. Its happening again tonight, as Lee plays a 1994 videotape in which three men are talking about Russell: David Byrne, Philip Glass, and Allen Ginsberg. Ginsberg, his face palsied by stroke, talks about how he admired Russells dexterity with words. Says Byrne: He would encourage me to appreciate stuff that I would just write off as being commercial. He was very enamored of Italian pop music, these very beautiful sounds but very commercial. He heard something in there.

If not for Lee, much of Russells work would have gone unheard. Over the years record producers would meet with him, interested in securing the rights to his dance songs to Go Bang and Is It All Over My Face? then lose interest when they learned Lee didnt own them. Regardless, Lee had the other tapes catalogued and moved them to storage. One day Steve Knutson of Audika Records called him up. He took a chance on releasing music no one was interested in, says Lee.

A remarkable element of Russells catalog is that, in snippets and full songs, it documents a relationship between two men, real partners, in an era that lacked that template. Gay relationships that mimicked heterosexual relationships -- I may be doing gay people a disservice by saying this -- but back then they didnt seem to exist, says Lee. It wasnt like there were other gay couples we were hanging out with. We were different. A lot of it had to do with the fact that Arthur was so singularly devoted to his music.

Lee, a real 9-to-5er, would go to work each morning in a printing shop, leaving Russell to write. They would meet for lunch so Lee could give him money and let him use the phone, and Russell would walk him home. They would eat dinner in front of

The Muppet Show on TV. Lee printed the flyers for his shows and covers for his albums. Hed always have his notebooks with him, and hed be jotting things down. It might be a conversation or something at another table, says Lee. One of the classic things hed say would be about a waiter or waitress. He would say, Oh, he just hates me. Or I was at the studio today and some guy erased my tape on purpose! My role was to be a cheerleader of sorts.

It wasnt perfect: Russell dallied with other men and women and ultimately contracted HIV through what Lee calls an indiscretion. Lee leafs through a photo album and comes across a picture of a woman Russell had an affair with in the early 80s. That was hard, he says. If someone has a fling with another guy, you sort of, I dont know, understand. This felt more emotional to me.

As the disease progressed, Russells output became increasingly intense and lyrical, leading to the tracks that would fuel his later revival (many appear on the albums

Calling Out of Context and

Another Thought). He performed in public regularly until the last year of his life and kept seeking funds for recording. Lee and Russell kept his illness largely secret; when he died, many people on the downtown arts scene were shocked. It was all pretty exhausting, says Lee. And yet to family and friends we tried to present that things were more or less OK.

Lee pulls out a wooden box full of photos and notebooks of Russells compositions. He would write lists of things, and sometimes they would become songs and sometimes not. Like this one: Ive got a new job, Ive got a new job, with strings over the world. I get lost in these sometimes. He comes across the notes for another unrecorded song: I Have a Boner. He laughs. Whats important for people to know was how playful he was, says Lee. He plays a song called Love Comes Back from Russells new album, a song culled from demo tapes Russell recorded where were sitting, as he was dying in 1992. Listen to his voice! says Lee. Isnt it beautiful? How come this wasnt released at the time? Thats the conundrum. At his memorial service, people were talking, and it was driving me crazy. I remember stopping people and saying, This is a song Arthur loved -- please listen to this. My poor friends and family, I dont know what they thought after Arthur died. I was

relentless. I never listened to any other music. I couldnt get away from it.

I think he was accepting toward his death, which came from the Buddhism, says Lee, recalling how Russell refused to use traps in the mouse- and roach-infested apartment. We didnt talk about him actually dying. Once when he saw me crying he said, Dont worry, Ill be OK. I think of that as his gentle way of accepting his

dying. I just thought our life would continue with me taking care of him. I wasnt really acknowledging that he would someday not be here.

Lee fiddles with his iPod. Let me play you another song. This is not going to be on the record, and Im upset about this.

An hour later, as Lee is walking me to the door, hes still leafing through the notebooks. Just give me another second. Take a look at this.

Steve Knutson, the owner of Audika Records, became obsessed with Russell after being given a copy of his dance track Treehouse/Schoolbell. He has spent three years editing nine hours of material into the 21 songs on the one-hour album. The deteriorating quarter-inch reels had to be baked in a convection oven before being digitally remastered, to fuse the information to the tape. Arthur absolutely wanted to be popular in his lifetime, says Knutson. But he didnt have the faculties to be that kind of person. Its one thing to be a brilliant songwriter; its another to play the game and market yourself. Till the late 80s and early 90s, those were ugly words.

He plays the album, which reveals a new side to Russell -- his adeptness with pop and folk is pretty stunning; his voice shimmers, reminiscent of Becks

Sea Change album and James Taylor. The material ranges from the early 1970s, when Russell was at music school in California, to the 1990s, when he was gravely ill at home. Goodbye Old Paint is an old public-domain cowboy ballad that Russell set to tabla and folk guitar. Hes like 20 years old, and hes mixing all these things together that shouldnt go together, but somehow they work. Its a preview of whats to come. One country song is a demo Russell sent to Randy Travis, on whom he had a crush (Travis didnt respond).Oh Fernanda Why is a favorite of Jens Lekmans. Habit of You is an upbeat love song that plinks along on a childs keyboard and samples of birds chirping and sounds like a Talking Heads B side from 1984. Its a terrific song, too weird and not poppy enough for its era, but today, it sounds perfect.

I tell this to Knutson, and his eyes tear up. Arthur would have hated all of this, he says. He was a contrarian by nature and kind of a control freak, so the idea of anyone putting out his music who wasnt him would have driven him crazy. He laughs. But hes probably madder at Tom.

If Russell wasnt made for his times, he was certainly made for ours. Prompted by the release in 2004 of two collections,

Calling Out of Context and

The World of Arthur Russell, a full-scale renaissance is in progress. Hes been subject to handsome reappraisals by Sasha Frere-Jones in

The New Yorker and Andy Battaglia on Slate.com. More releases have followed, including the reissue of 1994s out-of-print

Another Thought, the double album of instrumentals

First Thought Best Thought, and

Four Songs by Arthur Russell, an EP of covers by artists including Lekman, the Swedish romanticist, and Joel Gibb of queer Toronto group Hidden Cameras.

Because of downloading, its now absolutely regular for a person to describe their taste as being eclectic, says Lawrence. Arthur provides a route to the overwhelming mass of musical information available. Were now much more open to listening to new music as well as to music that cuts across and even nestles between genres. In this respect, Arthur was always ahead of his time, and now his time has come.

Send a letter to the editor about this article.