“You’re feeling nervous, aren’t you, boy? With your quiet voice and impeccable style,” Brandi Carlile sang in the opening lines of “The Joke” at the 2019 Grammy Awards. In that moment, I was watching TV at home, in awe of the singer as she strummed onstage in a black jacket sparkling with silver. I felt like she was right there, speaking to me. “Don’t ever let them steal your joy,” Carlile intoned. I knew what that joy was. I knew who “they” were too, those people who “kick dirt in your face” and “hate the way you shine.”

I also knew in that moment that Carlile was an artist of very rare caliber and power. Her sound was timeless, an anthem that could comfort the Other of any era. But my, how those words resonated in that moment. February 2019 marked two years into the Trump administration. The rosy days of It Gets Better and Supreme Court victories felt like a long-ago dream. Instead, hard-won LGBTQ+ rights were being clawed back, replaced by an escalating tide of violence and hatred against queer and trans people. The future felt so uncertain. But there was Carlile, with her ethereal voice, assuring us that she had “been to the movies” and “seen how it ends. And the joke’s on them.”

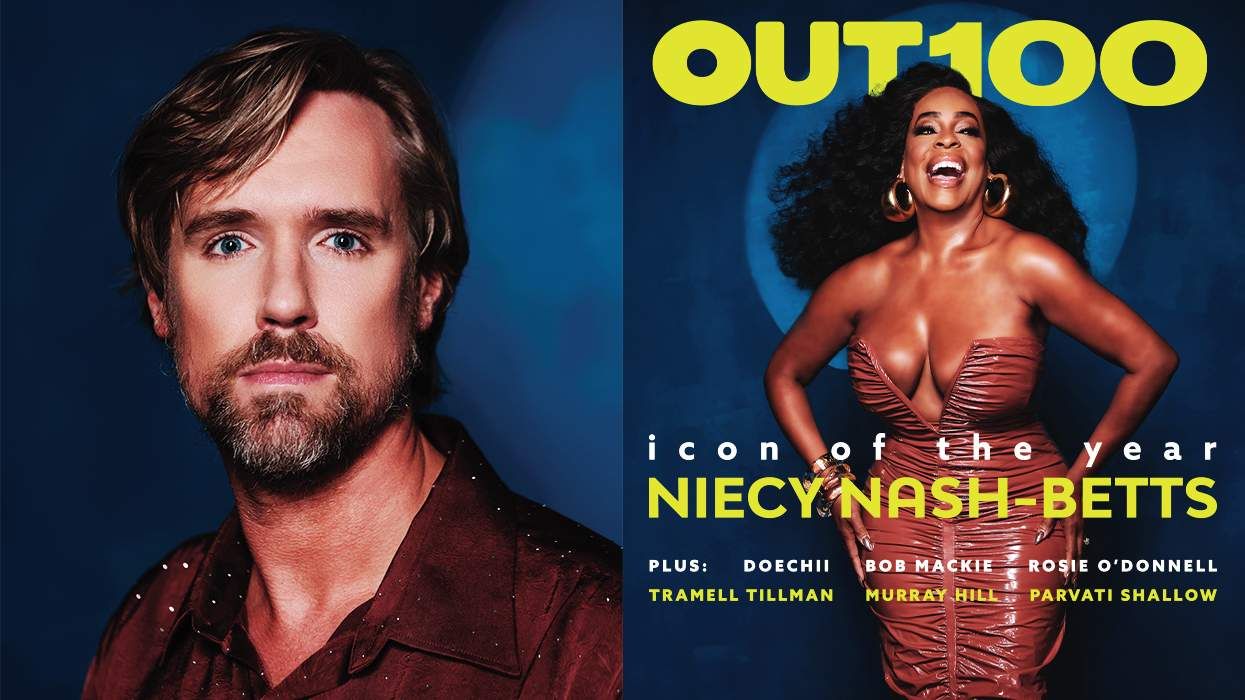

It is truly our honor to highlight Carlile as the cover star of the Out100, our annual list of LGBTQ+ changemakers. Her star has only grown brighter since 2019. This year alone, the lesbian icon took home two more Grammys for her song “Broken Horses” and appeared on the soundtrack of the summer, Barbie: The Album, where she covered “Closer to Fine” and introduced the Indigo Girls to a new generation. In our cover story, Carlile reflects on her fame, the responsibility she feels in an age of renewed anti-LGBTQ+ vitriol, and the special relationship she has with her fans. From her vantage point on the stage, she routinely witnesses the “congregation” — a gathering of women, LGBTQ+ people, and folks with “gentle ways” across generations. They receive her music’s hope and healing and return the gift with an awesome energy.

The Out100 is also a congregation. Here in this issue, Out’s editors have gathered Artists, Disruptors, Educators, Groundbreakers, Innovators, and Storytellers who, like Carlile, have used their platforms to pierce through the darkness this year. I’ve mentioned this in past letters, but the Out100 has a special place in my heart. As a closeted teen, I dared to peek at this list at my local Barnes & Noble. I marveled at the LGBTQ+ excellence and sheer possibilities of life on display. At the time, I didn’t know if I would even reach adulthood as a gay person. But there it was, printed in these pages: a future.

Across the country, right-wing forces are banning LGBTQ+ books and visibility in schools, libraries, and beyond. They are taking this promise of possibility away from our young people. But we’re not letting that happen without a fight. This year’s Out100 theme is Open Doors, and we’re proud to showcase figures like Wayne Brady, Pulse survivor Brandon J. Wolf, Sasha Colby, Gov. Maura Healey, and Dylan Mulvaney who hold the keys to a brighter future for our community.

After this year, we need all the open doors we can get. I felt that old despair return when O’Shae Sibley was fatally stabbed at a Brooklyn gas station after voguing to Beyoncé. When Lauri Carleton was murdered by a gunman at her California store for hanging a Pride flag. When threats of violence against our community continue to skyrocket — fueled by politicians who are effectively bartering our lives for votes.

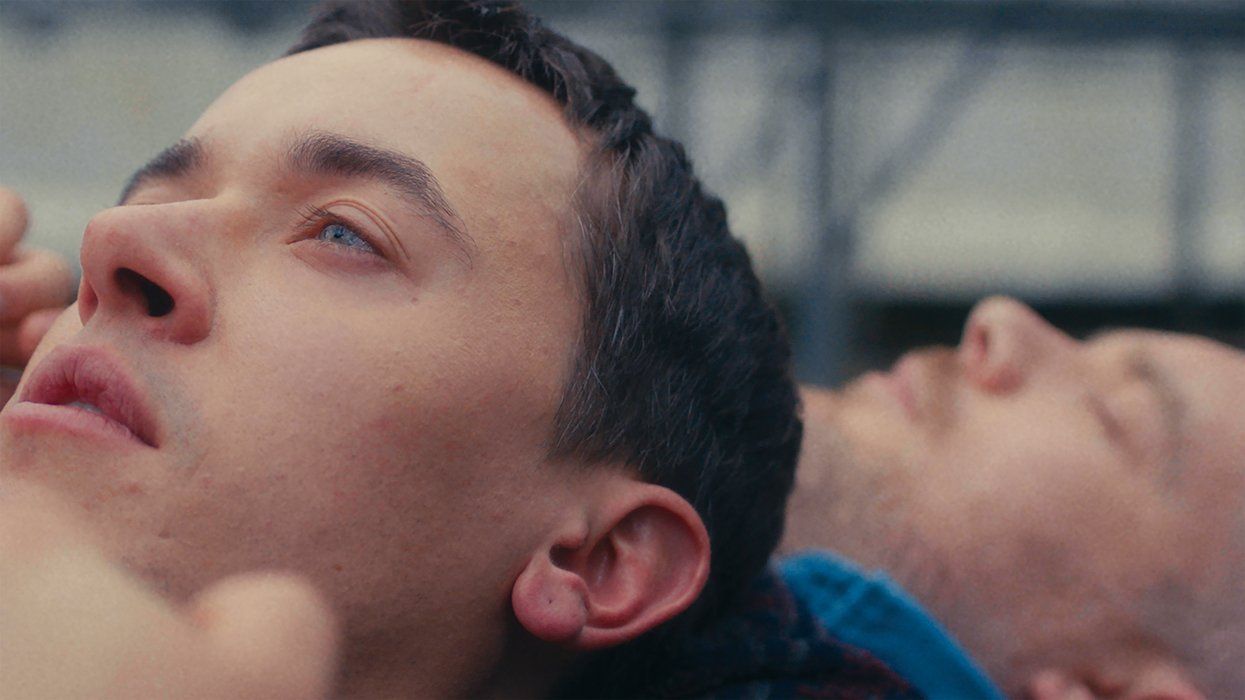

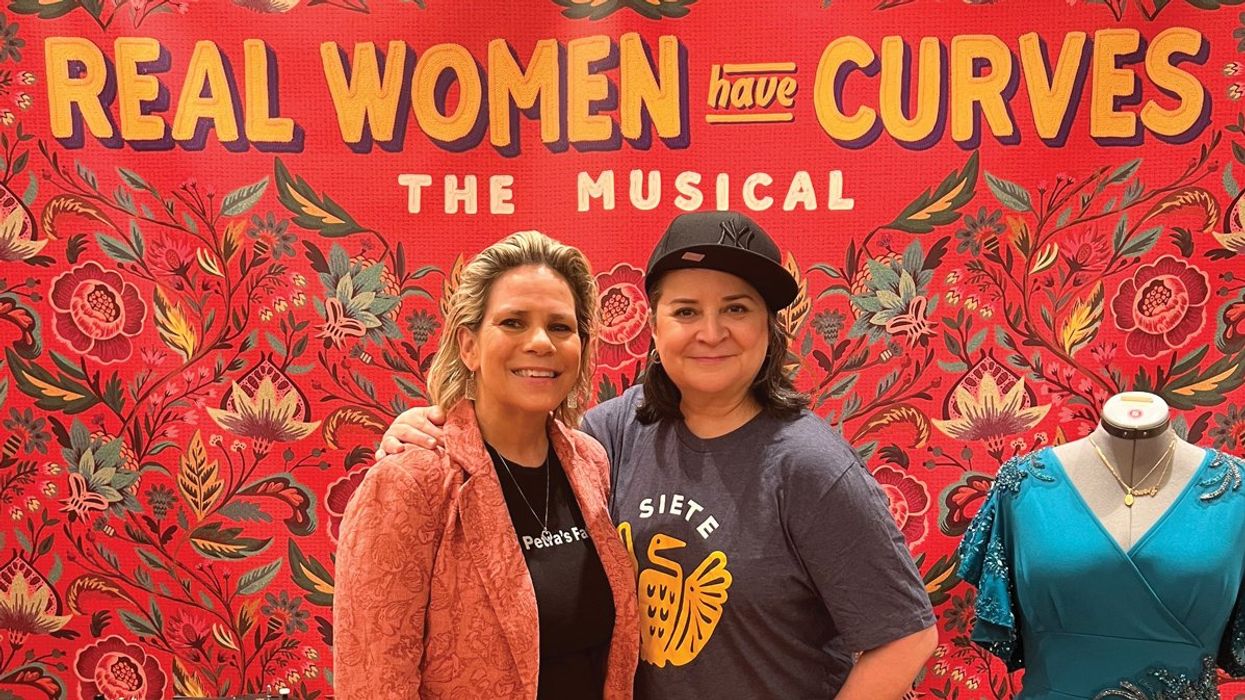

But in the face of evil and tragedy, this was also a year of triumph and possibility. The Out100 is an opportunity to reflect on figures who are at the heart of groundbreaking cultural moments moving our community forward: Kim Petras’s historic win at the Grammys; Murray Bartlett’s beautiful gay love story on HBO’s most-watched show, The Last of Us; Robin Roberts, America’s most beloved anchor, marrying her longtime partner, Amber Laign; Colman Domingo’s electrifying performance as Bayard Rustin in a long-overdue biopic of the Black gay civil rights icon; Brittney Griner’s liberation from Russian imprisonment and triumphant return to the WNBA.

Make no mistake, we are in a fight for our lives. But the Out100 reminds us that happy endings — that happiness itself — are within our grasp. We hope that the folks in these pages inspire you to keep voguing, keep waving a rainbow banner, and keep being out in the face of adversity. Carlile was right. We’ve seen the ending of this movie before. And the joke, indeed, is on those who dare try to steal our joy.

Sincerely,

Daniel Reynolds

Editor in chief, Out magazine

@dnlreynolds