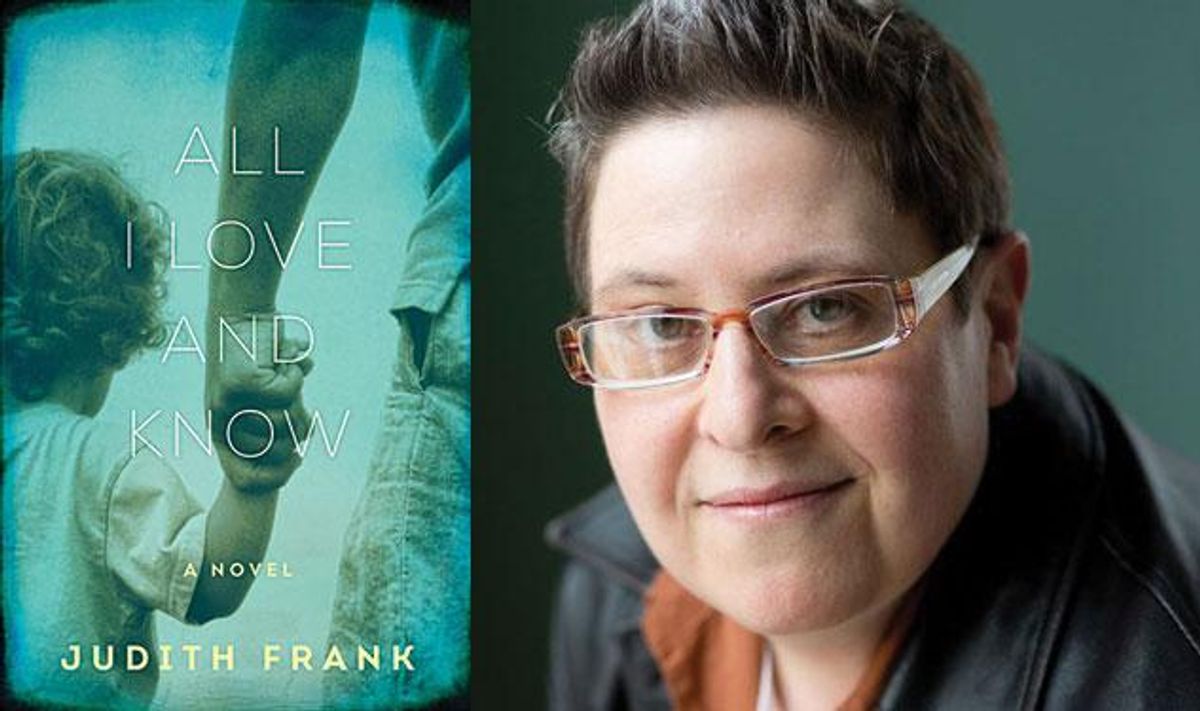

There's been a lot of buzz surrounding Judith Frank's second novel, All I Love And Know. The story follows Daniel and Matt, a New England couple who unexpectedly find themselves raising the children of Daniel's twin brother who was killed in a Jerusalem cafe-bombing. Critical of the Israeli occupation, both find it hard to reconcile the ache of their loss with their empathy for the suffering of the Palestinian people. As they attempt to navigate these feelings and a new life with two recently orphaned Israelis, the effects of Daniel's grief prove a strain on what used to be a solid relationship. Alternatively harrowing and humorous -- and always probing -- Frank masterfully packages an array of complex issues into an easily digestible read. And with the narrative's focus on same-sex marriage, gay parenting, and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it's singularly relevant in today's climate.

We caught up with the Amherst professor to discuss the book and these issues, along with her views on gay society and its representation in literature.

Out: What's really quite striking, given the context of your book, is that it happened to be released during this most recent spark in Israeli-Palestinian violence. What's that been like?

Judith Frank: That's been incredible. I've been trying to negotiate my joy over the book and my misery over the violence. It's really been ... intense. In her Oscar acceptance speech for her role in 12 Years A Slave, Lupita Nyong'o said, "It doesn't escape me for a minute that my happiness is based on somebody else's unhappiness," which I thought was a really smart and amazing thing to say. I feel a little bit that way as well. On the other hand, conversation is so hard with this topic, so maybe it's a moment when we should turn to the novel, to art, instead. Maybe instead of argumentation, we need a medium that can transform us in emotional ways.

Why did you decide to set the story between Israel and the United States, and in the early aughts?

Well, I knew that I wanted to start with the second Palestinian uprising that was in 2002-2003, and also that I wanted to end on the day gay marriage became legal in Massachusetts. That's all I knew. I didn't know what was going to happen on that last scene -- didn't know if anyone was getting married at all. But I knew I wanted to do a scene at the courthouse in Northampton, Massachusetts, where I went on that day - and it was such a festive, gorgeous day.

There's quite a bit of yourself in the novel: You lived in Israel for a time, your twin sister is married and lives there now, and you live in New England with your wife. Did those parallels make it easier or harder to talk about such an intense topic?

The way that I mediated my own experience was helpful. So, for example, writing about being an identical twin but doing it through men, that was really helpful to me. Clearly it's not an autobiographical novel in the sense that I never experienced losing anyone in a terrorist attack, and I actually lived in Israel in a really different time, much earlier. But I had to imagine: What would happen if my sister died? Having to imagine that was really really grueling and difficult. But doing that through these other characters helped me.

The book is a gripping read, but it can be quite taxing emotionally. What was your experience writing it?

It took me eight years to write it. And that's partly because I have a full-time job, and my kids were born in the middle of it. The hardest thing I experienced writing it was that I wanted to write the experience of grief that Daniel has when his twin brother dies, and he basically stays grief-stricken for the entire novel. I wanted to go deep into that experience and be true to it, and to be true to the ways in which it's not pretty, and the ways that he can be unsympathetic. And at the same time, I wanted to keep the reader attached to him.

But writing Matt, his younger partner, that gave me so much free reign. With Matt, I got to write about all the sort of selfish and petty things you would think if your partner was going through a really hard time, like, "What about me?" "Will I ever have sex again?" All of those things that you're not really allowed to think. It was a great outlet to be able to write those things for Matt.

Your first novel, Crybaby Butch, also dealt with grief. Why do you feel that it's such a worthy and necessary topic of exploration?

Your first novel, Crybaby Butch, also dealt with grief. Why do you feel that it's such a worthy and necessary topic of exploration?

Partly from the grief I've experience in my life. My dad died when I was 12, and I think a lot of my life I was learning how to live with that. I'm really interested in the impediments to grief. I know what it likes to feel very clean grief, like grief for lost pets, but grief isn't always like that. There are times when it's really muddied, or impeded by your relationship with the person who died. And that's something that I'm really interested in.

You chose to center your story around a male gay couple, yet there's arguably a much less visible representation of gay women in popular culture today. What drove your decision?

I know it sounds crass, but initially, I did it for commercial reasons. My first novel was about a lesbian couple -- it was about lesbian subcultures -- and it just got no interest from mainstream publishing. And I thought, Why don't I write about men and see what happens? Of course, once I made that decision it became so much a part of the novel: It wasn't artificial anymore. It allowed me to draw on the AIDS plot in the novel, and think about masculinity in Israel. It allowed me to do a lot of things. But originally it was, just, let's see if I can get mainstream interest in this. And, lo and behold, I did.

Matt was caught off guard at the prospect of getting married when it became legal. Did those feelings come from a real place?

It did. I think that all of my friends have been ambivalent about marriage. First of all, about marriage as the main issue that the gay community has advocated for, which creates a class of good gays who are just like straight people and a class of bad gays, who are presumably oversexed and immoral. And second, the question of getting married itself -- the question of whether you want to join that institution. I think every gay person I know who's gotten married has had to thrash through that question.

Marriage has progressed so fast that it's becoming hard for younger generations of gay people to realize that not everyone wants to get married. But you think there are still tensions surrounding the issue?

I think there are, at least for people -- I can't tell about you younger people, you younger people always surprise me -- but people from their thirties and up, I think there are. We've lived our lives as outsiders, and now, do we really want to be like everybody else? Do we want to enter this place of privilege that others continue to be excluded from?

Daniel, in particular, is very concerned about the image he gives off -- whether he and Matt fall into stereotypes. How concerned do you think the LGBT community needs to be about the public image we're giving off?

Oh that's, that's a big question... I think that there's this drive to look respectable, and that it's necessary to be accepted, but one of the things about Daniel is his drive to be respectable comes with some internalized homophobia. So, yeah, I'm against it. I'm for not being respectable. I say that as a highly respectable person who has a certain amount of self-irony about the ways in which I fit in.

And just to finish off, what does All I Love And Know mean to you?

I'm still figuring that out. Partly what it means to me is that you can write a story that is very specific and very political, and very challenging, and at the same time has broad appeal. I'm very excited that it seems that I pulled that off. I didn't know if I could.

All I Love and Knowis currently available.

Your first novel,

Your first novel,