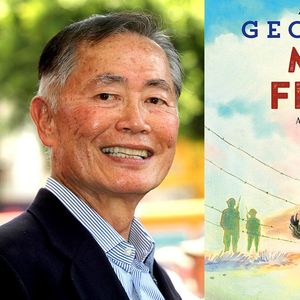

Pictured: A print of "Geronimo" from Warhol's 1986 "Cowboys and Indians" series

Andy Warhol and Las Vegas were made for one another. Or maybe they were made of one another. As Vegas boomed in the post-war period, luring celebrities, criminals and politicians like a neon-hued siren, Warhol was in Pittsburgh and then New York, honing his pop-infused aesthetic, an aesthetic very much inspired by and derivative of the soon-to-be celebrity kitsch showing nightly Las Vegas.

By 1963, the year after Warhol's first West Coast show, both he and Sin City were institutions in their own right. And both thrived on the same things: the public's obsession with celebrity and people willing to part with their money.

Las Vegas therefore becomes the perfect backdrop for viewing the pop master's work, which you can do starting tomorrow at the Bellagio hotel's Museum of Fine Art's latest exhibition, "Warhol Out West."

The 59-piece show features over 20 self-portraits of the famously narcissistic artist, as well as his photographs of select celebrities, including Marilyn Monroe and James Dean.

"The works we chose give an in-depth look at Warhol's diverse career which include paintings, screen prints, polaroids, a video and an installation and focus on his depiction of all things Western," says Tarissa Tiberti, Executive Director of the gallery. But the real jewels in the crown are images from Warhol's 1986 series, "Cowboys and Indians."

Copied from postcards and other pieces of Americana that celebrate and glorify the American west, these paintings are at once an exhalation and an indictment. "Warhol's intent was not to document any one point in history," says Tiberti. "His interest was to show how the idea of a particular subject matter has had an impact on our perceptions of it."

The Palmer Museum of Art at Pennsylvania State University tells viewers the series "forces us to question our notions of the 'hero' and 'heroine' of the American West and to ponder their relationship to the voiceless heroes of our Native American past." Geronimo "faces the viewer with a mixture of rage, strength, and fear." "Indian Head Nickel" turns the spotlight on ceaseless, commercialized stereotypes of both natives and westerners. And one of the series' most famous images, "Double Elvis," which portrays the entertainer as a gun-toting cowboy. But is this Elvis a hero or a conqueror? Either way, he does brisk business: a recent copy of the piece sold at auction for $37 million. Warhol would approve. "Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art," Warhol famously said with his trademark glibness. "Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art."

Of course Warhol wasn't as vapid as he wanted us to believe. Warhol had a deeper, quieter connection to the West. Toward the end of his life, in 1983, he created a series of prints of endangered animals to show at The American Museum of Natural History. It was a truly self-less act aimed not at making headlines, but at helping the helpless. And after his 1987 death, auctioneers sifting through his estate found 57 Navajo blankets and a collection of American Indian baskets, including a willow and red yucca root piece created by the Maidu people who once lived in a wide swath of land in what is now California, just on the other side of the Sierra Mountains from what would be Las Vegas.

Such utilitarian folk art appears inherently opposed to Warhol and Western culture's commercialization of art, and suggests, like "Cowboys and Indians," that Warhol was more than just an aficionado celebrating pop culture. He was a sage critiquing it.

"Warhol Out West" runs at the Bellagio's Museum of Fine Art through October 27, 2013.