For some, memories of the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and '90s remain burned into their memories. However, for the younger generation of gay men, who had no first hand experience of the AIDS crisis, their only exposure to it comes from chapters in textbooks and film footage. While those accounts may be striking, they can be difficult to identify with.

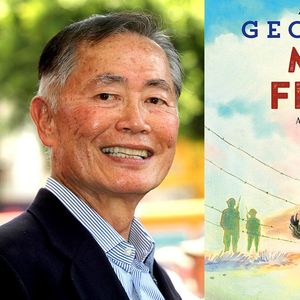

Now Christopher Glazek and Richard Espinosa--the founder and director, respectively, of the Yale AIDS Memorial Project--seek to preserve the stories of those who died of during the epidemic and making them accessible.

The project was recently featured in a New York Times story and is continuing to pick up supporters. We recently spoke with the duo to find out where the inspiration came from and why their generation would decide to dedicate so much time and energy to a time period that they never experienced themselves.

Out: How did the project start? What made you want to do it?

Christopher Glazek: I started to become interested in AIDS after I moved back to New York. I was at a friend's house for a funeral and her parents had gone to Yale and their friends were in town and they were telling stories about their old roommates and pals and then someone said "of course they're all dead now." Everyone there understood it was because of AIDS but I didn't and I asked "well, what happened to them?" That started me down a long path of reading about AIDS and the history of AIDS. I was interested in starting something that would intervene in the existing discourse, that wasn't just a book or an essay. How can you investigate and collaborate in ways that are not just a single person writing.I think there's been this mindset for a long time that there are too many urgent issues to deal with in the present, politically. I think until now it might have seemed a bit ridiculous to throw our attention to the past, but I think that the gay community is in a place of enough comfort where it does make sense to take a look at this history and really process it, because it hasn't been processed.

Yale has the reputation as being the "Gay Ivy," what would you have to say about that?

Richard Espinosa:It's true; you can't really throw a brick without hitting a couple of gay guys at Yale. There's a great diversity in terms of different ways of being gay and kind of expressing yourself. But the gay community [at Yale] isn't really politically engaged. That's something we're trying to address more as of late. It's a great privilege to go to a school like Yale and if you're going through that institution you should have a good idea of how that privilege and that power works.

RE: For me, knowing this history is really important, for young gay men especially. A couple weeks ago we had pride and you need to understand that you're part of community and part of a history of people who were backed into a corner. Everyone was dying and no one knew what was happening and no one was trying to help them. These people came together and they fought back. Being part of this community is being part of a history of people who fought and spoke out. The stories we're trying to tell with the project are really about the people, not how they died, but the way that they lived.

Do you think today's young gay men are a bit flippant about AIDS.

CG: I think there's an "out-of-sight, out-of-mind" thing because a lot of people aren't touched by AIDS. The disease has also become manageable and conic rather than a death sentence, something instantaneous and deadly. It's another goal of the project, to reintroduce the epidemic to a younger generation to make sure that that same thing doesn't happen again.

RE: I guess coming of age after the most massive wave of AIDS death is an interesting position to be in. A lot of young people were born after the advent of Protease inhibitor drugs. What we're trying to do is reengage people with this history, so that people could understand not only their history but also their own health. I believe our generation owes our lives to those who lived, fought, and died in the '80s and '90s. Like ACT UP, for example, which made it so we were born into a world where people were aware of AIDS. AIDS, this historical trauma, belongs to us; it's part of our history as well.

You said you wanted to expand the project to other institutions, how are you going to do that?

RE: What we're about to embark on is the website which is really the major part of the project. We're making it very user friendly so we can give it to other institutions. The Yale Project is the first step. The goal is to help other institutions set up their own localized AIDS memorials.

CG: It's not just the technology we want to give people; we want to tell people how we brought ourselves to make this. It's really exciting to imagine iterations of this of at other institutions. If you set it up at another institution, the stories are going to be much different. You may not be engaged with AIDS history, or activism, but you're probably engaged in the institution. You can spout numbers at people all you want, but that doesn't have a huge effect. It's about making it hit home.

What will the website look like?

RE: Our generation has developed these muscles with regards to social networks. Facebook and Twitter have these amazing abilities to get lost in them. You'll start somewhere and end up somewhere else and you're not sure how you got there. We wanna leverage that moving about the internet. We take these stories and heavily link them to each other. We want to create something that's rich enough to explore. You'll also be able to search the website, so you can find out who in your dorm died of AIDS or who on the swim team died of AIDS.

We're trying to take something as complex as the AIDS epidemic and make it palpable and understandable for another generation. It'll bring the stories much closer to people. AIDS memorial are often just a list of names with no kind of contextualizing information and they can be very beautiful depending on how they are presented, but if you're not personally acquainted with one of those names, it's difficult to connect. The really important difference of what we're doing compared to other AIDS memorial projects is that we're telling the stories.

How's the project going now and where do you see it going?

RE: It's going great. We launched the project in June after working on it for a year. The interest from the press has been great. There's a lot of different components to the project: there's the journal that we want to publish once a year, there's the website that is really the backbone of the whole thing, and we want to have public programming, lectures or symposiums to kind of open it up to the community to hear experts talk about the issues.

Why Yale? Is this a form of the elite power structure taking ownership of this or does that matter?

CG: We're in the position of being in the vanguard here. It's not about celebrating the university it's about remembering lives lost. Obviously we went to Yale so that's a part of it. That being said, Yale's a good place to do it. Yale also has a long history with memorial; there are a million different memorials on campus. Yale also has a history of AIDS activism and AIDS research.

RE: It's also an institution whose alumnae community has the resources to develop the infrastructure we need.

For more information or to donate to the Yale AIDS Memorial Project, visit YaleAIDSMemorialProject.org