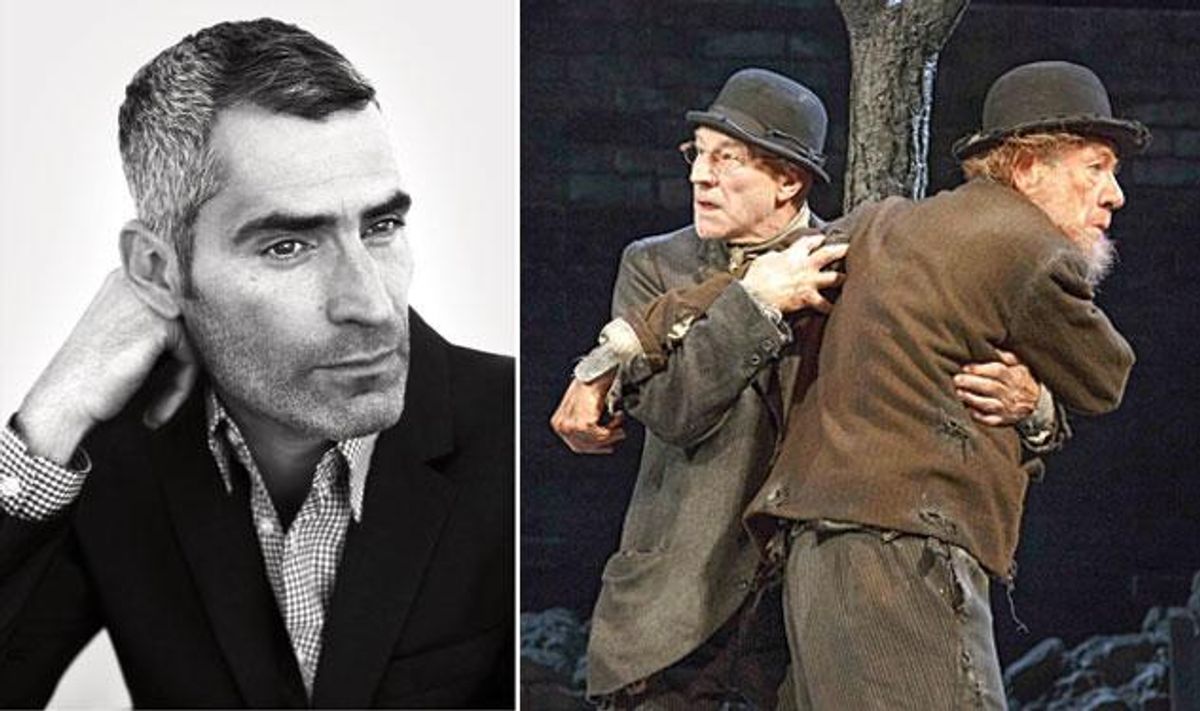

Photography by Danielle St. Laurent

My teachers at school were generally horrible, and I've barely a good word to say for any of them. Rather than open up the world to us, they seemed determined to close it down. At the time, my school followed a misbegotten practice of streaming pupils into A, B, and C bands that we were assigned to at the age of 11 based solely on our academic skills. I spent many years feeling angry about being placed in the B band, where we were neither expected to go to university nor encouraged to try. As for the kids in the C band, one can only imagine what shrunken hopes and dreams they were reduced to.

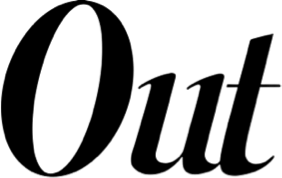

But there was one category of teacher that transcended that miserable experience of relegation and repudiation. They were the English and drama teachers, men and women who loved words and taught us to love them, too. There was Mrs. Thompson, benevolent, maternal, and the first English teacher I can recall; there was Mr. Lindsay, a World War II pilot who had bitten off the tip of his tongue during a crash dive -- and survived to tell the tale; and there was Mr. McConnell, a buoyant Irishman who allowed us to call him Arnie and opened up an exciting new world for me the day he suggested I read Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot. I'd never seen language used in that way, and I tripped and stumbled my way through the text until I felt the first rays of illumination. And then I performed it, first for my end-of-year exam and subsequently for the school. It was thrilling, affirming, and defining, and the play has accompanied me through life ever since, a kind of codex from which I draw my own philosophy.

I might have forgotten the enormous debt I owe those teachers if it weren't for a striking coincidence of having two features in this issue in which a teacher plays a transformative role in the life of their teenage student. For both the actor Matt Bomer, and our own executive editor, Jerry Portwood, the life-changing text was Larry Kramer's The Normal Heart, which both men discovered at the hands of enlightened teachers. For Portwood, reading The Normal Heart at the age of 15 was a profound awakening.

"These people in this play were nothing like me, and I needed to understand them," he writes. "These were my people." Bomer, who discovered the play when he was 14, had a similar experience. "It wasn't until I read Larry's work that I had any kind of understanding as to what was really going on in the world around me," he tells Shana Naomi Krochmal in this month's cover story. "It just lit this fire in my belly."

The Normal Heart led Bomer to Tony Kushner's Angels in America, and thus the world expands. That both these plays would end up being filmed for HBO with all-star casts is a testament to the role playwrights and novelists have played in writing our history. It's also no coincidence that a generation of younger actors -- Zachary Quinto, Jim Parsons, and Bomer among them -- have found the courage to come out largely as a result of being in these plays, and recognizing and wanting to honor the struggles of an earlier generation. In this way they pass the torch forward.

That Waiting for Godot is not the same kind of play as The Normal Heart or Angels in America goes without saying, but it was only recently -- after watching the landmark production with Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart on Broadway -- that I fully appreciated how, in his own subtle way, Beckett gave me license to think of men in romantic relation to one another. His central characters, Vladimir and Estragon, may or may not be lovers, but they certainly love one another. That may seem like slim pickings, but it was enough, in a provincial school in the 1980s, to make a difference.