Entertainment

CONTACTStaffCAREER OPPORTUNITIESADVERTISE WITH USPRIVACY POLICYPRIVACY PREFERENCESTERMS OF USELEGAL NOTICE

© 2024 Pride Publishing Inc.

All Rights reserved

All Rights reserved

By continuing to use our site, you agree to our Private Policy and Terms of Use.

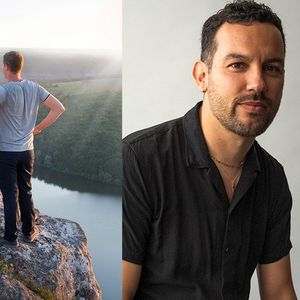

In 1884, Charles Crozat Converse, a Pennsylvania attorney with a reformers streak, perceived a gap in the English language and made a bold proposal for filling it: to add thon (that + one) as a substitute for he or she. Thon could be applied whenever it wasnt convenient or necessary to give the sex of the person being discussed. Converse gave this sentence as an example: If Mr. or Mrs. A comes to the courthouse on Monday next, I will be there to meet thon. And thon had its day in court. The arguments of Converse, whose skills included composition (he wrote inspirational hymns) as well as rhetoric, convinced the editors of Funk & Wagnalls Dictionary to include thon in its lexicon. There it remained until 1964, when it was conceded that no one used the word or probably ever would. Thon joined e, en, hiser, hse, hann, tey, ve, xe, and the sublime ip in the penitentiary for invented gender-neutral (also known as epicene) third-person pronouns. The only visitors allowed: linguists, trannies, and a few sci-fi geeks. Its not that thon wasnt useful. We still lack a good gender-neutral pronoun. And we could use one. They/them and one are frequent stand-ins but can be misleading. And while its easy to popularize new nouns (ginormous, vajayjay, window treatment), its tougher to crack the basic DNA of English. Words like he and she belong to a type of word that we call closed class -- that doesnt allow new members easily, explains Elaine Stotko, an associate professor in the School of Education at Johns Hopkins University, and a trained linguist. Last fall, in an article in the journal American Speech, Stotko and a coauthor announced a stunning discovery: Some schoolkids in Baltimore have quite spontaneously started using an epicene pronoun of their own -- yo. Not yo as in all in the game, yo, all in the game (Omar Devone Little, The Wire) but rather: Yo been runnin the halls. She aint really go with yo. You acting like I said what yo said. And my favorite: Peep yo! (Translation: Look at him/her!) Charles Crozat Converse would probably be kicking his heels for joy. The Baltimore schoolchildren use yo precisely as Converse wished thon to be used (slang notwithstanding). People before them have tried to do this. Somehow these kids have hit on something thats working, says Stotko, a vivacious redhead in her fifties who has decorated her Johns Hopkins office with images of cats and cutouts of New Yorker cartoons. Somehow its working for them, and I cant answer why. Stotkos interest in epicene pronouns is not merely academic. She has a transgender son, Adrian Quintero, who was born a biological female 29 years ago. Around the same time that Stotko was first investigating reports of yo, Quintero called up, coincidentally, with something important to share: She wanted to try out living somewhere between he and she. Quintero, in his mid 20s at the time, had just seen a panel discussion of transgender people at a university. What Quintero saw was moving; he recognized himself on the stage. I called her the next day, he says, raising his gaze from his hands to make eye contact with his mother as he speaks. Weve always had that kind of relationship where Im always like kind of processing big things with her and saying I think I relate to this; Im not quite sure. And she was like, You dont have to figure it out right now. Since that moment Stotko has accompanied Quintero every step of the journey to his new, self-determined identity -- including picking a pronoun for himself. There was a period of time you were trying to get me to use hir and ze? Zir? Well, whatever... says Stotko, recalling an early conversation. You just kept saying, You cant change that part of speech! Quintero interjects. Yeah, and I think he was taking it as I didnt want to personally, Stotko says. And I kept saying Linguistically, this is really hard. Eventually they hit upon a compromise: At home Stotko and her husband refer to Quintero as Q; some of Quinteros friends call him that too. But with new acquaintances Quintero is now simply he or him, generally. Mostly, Quintero doesnt have to explain. Last year, he was ready to surgically remove the breasts that didnt match his self-image. Stotko was at his bedside after the double mastectomy. Fortnightly injections of testosterone have yielded a fine sprinkling of hairs on his chin and dropped the pitch of his voice. With his close-cropped hair and thrift store ski jacket, Quintero is boyishly cute. When he picked me up from the train station in Baltimore, I noticed a couple of guys checking him out through the window of Quinteros silver Honda. In the 20th century Americans constantly tinkered with the language to achieve noble social goals: to remedy old racial wounds (consider the path from negro to colored to black to African-American); to accord women equal treatment (drag queens and pageant contestants are possibly the last people who take Miss seriously); and shower sensitivity on any group you could imagine (people with disabilities, Native Americans). But the popular vocabulary for transgender people has lagged pitifully -- a result of prejudice and simple cluelessness. Within the trans community ze and hir are sometimes used as umbrella pronouns, conveying a rainbow of sexual personae and tastes. I felt using gender-specific pronouns was a way of making my biology important in a way it wasnt in my daily life, says S. Bear Bergmann, a writer who identifies as queer and trans masculine, and who has used ze and hir in hir writing and speech for more than a decade. Bear likes yo in theory but rejects the notion that it is somehow more natural than ze/hir. Theres a cultural value of what is natural and spontaneous as opposed to what is creative, ze says. But you know, we no longer live in caves or eat what we can pick off of bushes. We have arranged the entire universe to suit us, and yet its still somehow perceived as more valid that teenagers in one school system in the U.S. are doing this. As Elaine Stotko points out, theres a big difference between ze and yo: The Baltimore schoolkids arent talking about transgender people. And she insists that theres no connection between yo and her sons journey. They are separate matters that just happened to touch her life at the same moment. But sitting behind the wheel on the ride back to Baltimores train station, Quintero tells me the correlation is pleasing to him. I personally hope our language will evolve in such a way that theres an agreed-upon set of gender-neutral pronouns, he says. Im not so attached to ze and hir. I dont think yo is gonna be a part of it, says Stotko. Well, its OK with me, says Quintero. Mom looks momentarily ruffled. I dont want to be referred to as yo. Send a letter to the editor about this article.

Want more breaking equality news & trending entertainment stories?

Check out our NEW 24/7 streaming service: the Advocate Channel!

Download the Advocate Channel App for your mobile phone and your favorite streaming device!

From our Sponsors

Most Popular

38 Male Celebs Who Did Full Frontal Scenes

November 17 2023 5:18 PM

These are all the celebrities Who came out as LGBTQ+ in 2023

December 31 2023 12:19 PM

32 LGBTQ+ Celebs You Can Follow on OnlyFans

October 25 2023 3:15 PM

26 actors who showed bare ass in movies & TV shows

February 28 2024 1:50 PM

21 LGBTQ+ reality dating shows & where to watch them

April 03 2024 4:01 PM

15 Unforgettable Gay Kissing Scenes From TV & Movies

February 14 2024 10:20 AM

14 queens who quit or retired from drag after 'RuPaul's Drag Race'

April 04 2024 12:56 PM

40 steamy celebrity Calvin Klein ads we'll always be thirsty for

January 04 2024 10:54 AM

The 15 Best LGBTQ+ Movies of 2023

December 04 2023 10:32 AM

Watch Now: Advocate Channel

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Trending Stories & News

For more news and videos on advocatechannel.com, click here.

Latest Stories

April 17, 2024

19h

Kennedy Davenport finally explains the rumored 'All Stars 3' drama with Trixie Mattel

April 16 2024 4:16 PM

Watch the queens from 'Drag Race Live' hilariously reveal Out's RuPaul cover

April 16 2024 4:10 PM

Noah Beck claps back at people who assumed he's gay for hugging a male friend

April 16 2024 4:03 PM

Jonathan Bailey's next gig is being lined up & it involves dinosaurs & ScarJo

April 16 2024 2:12 PM

Queens were showing out & shining bright at The Center's fundraising dinner

April 16 2024 1:37 PM

Wanna hookup internationally? Grindr's new feature helps you do that

April 16 2024 12:58 PM

Ricky Martin reveals 'very discreet' man he's met in exclusive new 'Palm Royale' clip

April 16 2024 11:56 AM

This morning was PURE CHAOS in the Bravo universe

April 15 2024 7:35 PM

Wrestling stud Anthony Bowens stuns in sweaty & steamy gym selfie

April 15 2024 4:56 PM

Billie Eilish kissed a girl at Coachella & we're FREAKING OUT

April 15 2024 4:19 PM

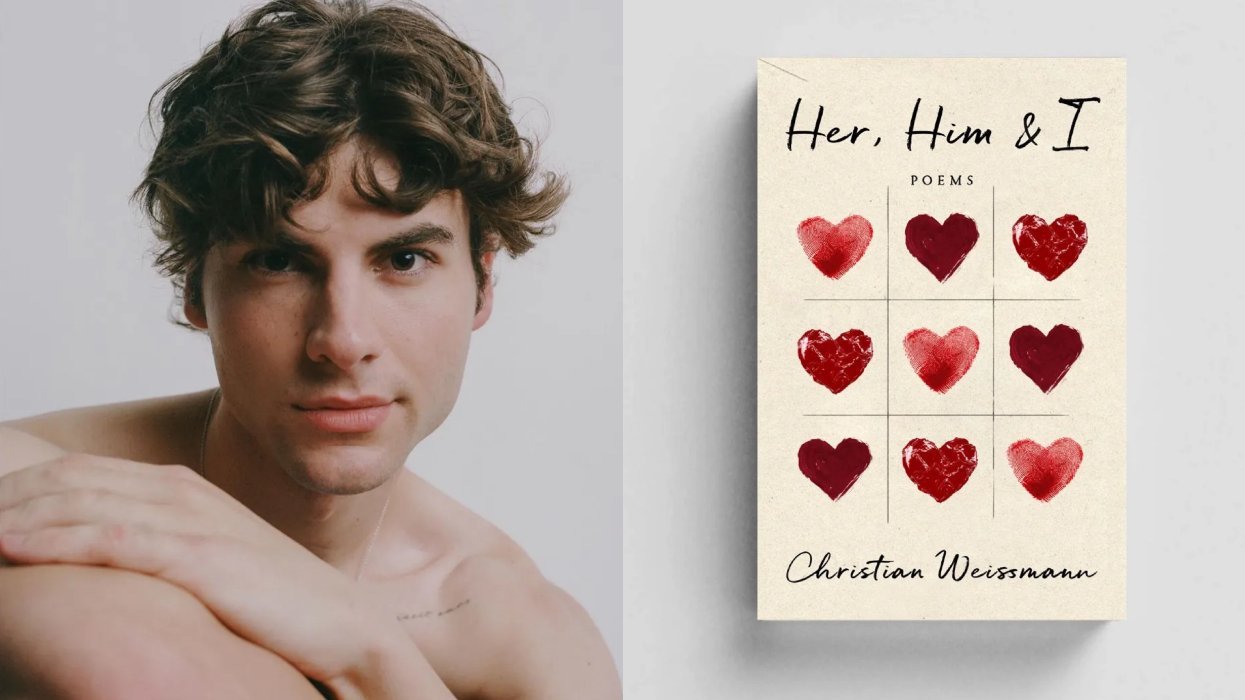

Writing helped save one queer poet's life—now he wants to help others feel seen & heard

April 15 2024 4:08 PM